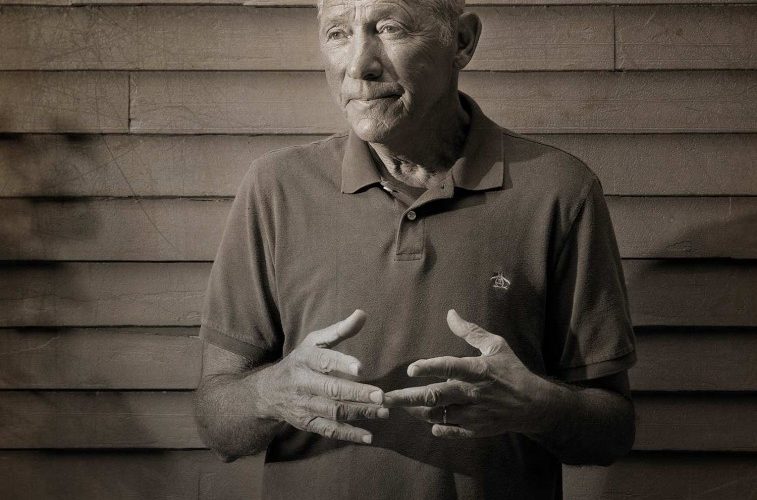

Prolific playwright and Massachusetts native Israel Horovitz is the heartbeat behind Gloucester’s theater scene. By Julie Batten – Photographs by Dana Smith

It used to be that on a hot afternoon in July, the Horovitz family of Wakefield would pile themselves into the family car and head up to Pleasant Pond in South Hamilton, where the senior Horovitz, Julius, had bought a lakeside “shack” for $1,200.

“We were really more on the swamp side of the lake,” explains Julius’s son, the internationally renowned playwright Israel Horovitz, over breakfast at Zeke’s in Gloucester one day this past summer. “That’s really when theatre came into my life,” he goes on, ordering a glass of ice water to go with his omelet. “My mother was a big welcomer, and theatre, after all, is a form of feeding an audience.”

Well, either that, or back then there was something in the water beyond a few lily pads, because Horovitz has gone on to write more than 70 produced plays in his lifetime-including Line, which has run for nearly 40 years off-off Broadway-many of which have been translated into more than 30 languages.

For the last three decades, the playwright has lived on and off in Gloucester, in part because he served as the Artistic Director of Gloucester Stage Company for 28 seasons before handing the reins over to current Artistic Director Eric Engel in 2007. He still summers in Gloucester, however, when he isn’t living in one of his other residences around the globe. When he does return to Gloucester, he says, “I feel like I’ve come home.”

Then again, it’s all part of the craft. “Writers are pretty steady people,” says Horovitz. “They tend to come back to places.” Horovitz decidedly still has a life here, with a “good size” group of cousins left, along with five children and a few grandchildren, all touching down at different times of the year in one of the “best places I’ve ever seen.” And boy, he’s seen a lot.

Horovitz first went to Paris with his first wife when their daughter, Rachael, was a mere 18 months old. “I remember seeing Simone de Beauvoir at a cafe. She smiled, and I smiled, and I thought, ‘Wow-this is a lucky place for me.'” Now in his 70s, Horovitz is the most translated American playwright in France, with over 50 of his plays having been produced in Paris. This past year, he spent as much time there as he did in New York, Gloucester, Moscow, Florida, California, Washington, London, and Ireland combined.

“I travel a lot, but never like a tourist; I get to be in people’s lives in a very intimate way,” Horovitz says. That’s because playwriting, the theatre business itself, is about the act of listening to people, according to Horovitz. And as long as people keep inviting him to see their productions of his plays performed anew, it seems he will continue to have plenty of opportunities to do just that. After all, what better method than traveling the world to learn the ways people talk when you’re in the business of producing dialogue?

“I always tell young writers that if they can write the way people talk, they can do this,” Horovitz says. In many of the places that Horovitz has traveled to, he has encouraged the troupes of actors he encounters to start their own theatre companies.

“They always ask me, ‘How can we continue to do this? What can I do with my life?’ And I tell them, ‘Well, the phone’s not going to ring. It’s not ringing for me or anyone else. If you want to do something, you can’t wait to be invited, you’ve just got to do it.'” For evidence that he actually lives that philosophy, there’s Harlequin Productions, a professional theater in Olympia, Washington; the Arts Garage in Delray Beach, Florida; the Compagnia Horovitz Paciotto in Spoleto, Italy; and the Festival d’Avignon in the south of France-all places, among many, where people have been touched by an Israel Horovitz play or been inspired to go on and produce other works by the author.

Horovitz’s work is, arguably, welcomed in all theatres, but never more than in his very own Gloucester Stage, where he has an agreement with Engel to contribute one new work to the line-up every two years.

“I [always] saw Gloucester Stage as a birthing center; [the audience] was happy to see a new play developing and I would tell them, ‘Some day, when this play is in New York and costs a hundred bucks a ticket, you can say you saw it in Gloucester for 20 dollars,'” says Horovitz.

Often, it was plays that came out of Horovitz’s work with the renowned New York Playwrights Lab, a group that he started in 1975 and with which he continues today as Artistic Director, that made it up to the North Shore. In his characteristic manner of turning playwriting into a collaborative event, the New York Playwrights Lab existed originally as something of a secret society for an elite cartel of playwrights-except it wasn’t. The playwright insists it was mostly a word-of-mouth thing that was going on in New York those days; “There was a small group of us, about 10 or 15, that came together each week for 20 weeks and had to bring five pages with us. At the end of that time, we’d each have a new play.”

By the time Horovitz found himself reciting poetry to Beckett in Paris bars, he had already had great success with his own minimalist plays, such as Line, a play about five characters waiting in line for a ticket booth to open, that is now in its 35th year playing off-off Broadway at the 13th Street Repertory Company. The Indian Wants the Bronx, a play about racism that introduced future film and stage star Al Pacino and won an Obie Award in 1968 for Best Play. At the New York Playwrights Lab, he continued to write plays that carry his trademark blend of what he calls “funny, dark, scary,” earning numerous awards for himself in the process, including a second Obie, the Drama Desk Award, The Sony Radio Academy Award (for Man In Snow on BBC-Radio 4) and an Award in Literature from The American Academy of Arts and Letters, among many others.

By the time Horovitz found himself reciting poetry to Beckett in Paris bars, he had already had great success with his own minimalist plays, such as Line, a play about five characters waiting in line for a ticket booth to open, that is now in its 35th year playing off-off Broadway at the 13th Street Repertory Company. The Indian Wants the Bronx, a play about racism that introduced future film and stage star Al Pacino and won an Obie Award in 1968 for Best Play. At the New York Playwrights Lab, he continued to write plays that carry his trademark blend of what he calls “funny, dark, scary,” earning numerous awards for himself in the process, including a second Obie, the Drama Desk Award, The Sony Radio Academy Award (for Man In Snow on BBC-Radio 4) and an Award in Literature from The American Academy of Arts and Letters, among many others.

Horovitz attributes his playwriting style to the way he learned to deal with some of life’s inequities early on. “My mother was very funny; she had a wonderful sense of humor and a terrible life-I learned from her that the easiest way to involve an audience in a very serious play is to make them laugh and feel comfortable.” Horovitz explains that “All art is born of the suffering of the child-there is no exception.”

When asked how it is that all of his children have become artists in their own right and what this might imply about the suffering in their lives, he is quick to laugh. “If you asked them one at a time, they would probably complain that they were dragged to rehearsals of my plays and speeches and all of that stuff,” he says. Horovitz’s five children include film producer Rachael Horovitz, television producer-director Matthew Horovitz, and hip-hop star Adam Horovitz, best known as Ad-Rock of The Beastie Boys, all with his first wife, artist Doris Keefe (now deceased). He also has twins Hannah and Oliver with his current wife, notable marathoner Gillian Adams. “The thing that amazes me is how your kids pick up where you left off,” Horovitz says. “The twins are both very sporty, very athletic. But all of them are doing things closer to what I do than they might like to admit.”

On his 70th birthday three years ago, Horovitz was decorated by the French government as Commandeur dans l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, and the 70/70 Project celebrated production of 70 of his plays around the world, including in the national theatres of Nigeria, Benin, Greece, and Ghana. He recently published his memoir, A New Yorker in Paris (the publisher nixed the possibility of A Bostonian in Paris, apparently, saying it didn’t have quite the same panache) in French and will begin shooting a film adaptation of his play My Old Lady in Paris this fall. “I wasn’t born into this, you know. My father was a truck driver.” Sure. If only those Pleasant Pond bullfrogs could talk.