Gardner Mattress has been using time-tested methods to craft beds in Salem for 80 years. By Jeanne O’Brien Coffey – photographs by Michael Basu

Not many people have to deal with sleeping customers for a living. But it’s something Kirk Forsyth, general manager of Gardner Mattress in Salem, has faced more than once—and can usually turn to his advantage. When one man fell asleep on a mattress in the corner of the store early one Sunday afternoon, Forsyth let him enjoy his snooze while other customers busily shopped around him—even occasionally lying on the bed next to him. Forsyth kept the store open a bit late, helping people with their selections. When the napper finally roused himself, nearly two and a half hours later, Forsyth walked over with an order form and said, “Let’s write this one up.” And the man happily did.

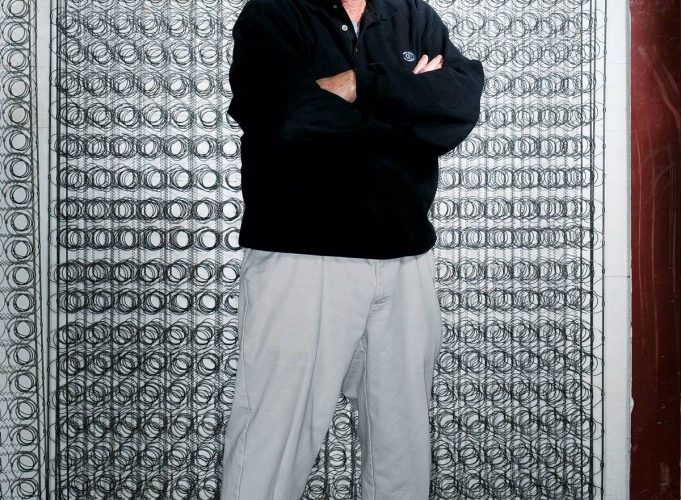

This personal touch, combined with a commitment to a high quality product, has kept Gardner Mattress in business for 80 years, explains Gardner Sisk, who bought the business from his grandfather, founder Alan Gardner, in 1976. “Customer service is the one thing we can do better,” says Sisk. “We make sure our service is second to none—superior to anybody else’s. It’s something that the bigger guys can’t do, because it’s costly.”

Cost is the top concern for large bedding manufacturers these days, Sisk says. As the bedding industry at large has become increasingly commoditized, with investors seeking to squeeze out every penny, materials that used to be standard in mattresses are being left out. For example, a border rod—a six-dollar piece of metal that gives structural support—doesn’t add much to the cost of a mattress at Gardner, which produces roughly 6,000 units a year. But larger manufacturers that can churn out 50,000 mattresses annually view dropping that six-dollar piece as a significant cost savings, explains Forsyth, who is Sisk’s stepson and also in charge of the company’s day-to-day operations. Gesturing toward a cut-away in a mattress manufactured by a competitor, Forsyth notes, “All it is is a piece of plastic, two layers of foam, and a piece of fabric. These things are cheap to manufacture. There’s nothing inside them, and they don’t wear well.”

Commercial bedding, with very few exceptions, is designed for price, agrees Sisk. “The internal materials, the way they are put together—they are not very well made. They feel good, they look good, but they don’t perform well.” He admits that his company took a hit when Sleepy’s, a discount chain with more than 600 retail outlets, came to Massachusetts. The recession in 2007 compounded the pressure and caused them to reexamine their business model. As a result, the company cut staff levels 30 percent and reduced overhead to stay in business.

Now, with the business back on firm footing, Sisk says people are starting to recognize the difference and return to Gardner. “If somebody comes in here and isn’t [focused] strictly [on] price [and] if we don’t sell them, we feel as though we haven’t done a good enough job educating them, because our product is so much better,” Sisk says. Over the past two years, at least, education has paid off, with healthy double-digit increases in the percentage of sales since 2010.

Unlike the large manufacturers, who fill their mattresses primarily with polyurethane foam, Gardner uses domestically sourced cotton to fill its mattresses—and no chemical flame retardant. “As people are getting more conscious of their environment and wanting to subject their bodies to fewer chemicals, it fits right into what we do really well,” Forsyth says. “We don’t have to change what we do. It’s come full circle, where people are once again interested in what we’ve always made.”

Take a walk through the Gardner factory, and you won’t smell anything harsh or unpleasant, because the company uses properly treated, high quality materials and water-based adhesives. The facility is clean and brightly lit, with employees constructing mattresses much the way they have for the past 80 years, as the framed historic photos dotting the store show. “It’s a good place to work,” Sisk says. “We listen to our employees about the kind of environment they want.”

Perhaps that’s why so many of the 18 employees, who work in three stores, the front office, and the factory, have been with Gardner for so long. Foreman Eddie Carter has been with the company for 28 years, and over the last 25 years, Steve Popp has built all the box springs, working nights until the 1990s, when an expansion brought with it enough room to make mattresses and box springs at the same time.

Gardner staff constructing mattresses.

Gardner keeps no inventory, so each mattress is built when a customer orders it. Fabrication can take anywhere from 45 minutes for a memory foam mattress that simply requires a cover to two hours for an innerspring mattress, which needs to be filled, tufted, and covered.

The menacing tufting machine, with needles that are more than a foot long, demands to be approached with care. But it is not nearly as threatening as the inner springs for the mattresses, which come tightly compressed in bundles of about a dozen. Traditionally, workers cut the bundles apart in a specific order or risk getting seriously hurt, as thousands of pounds of pressure released. Fortunately, the factory now has a machine to unpack the springs automatically, eliminating that danger from the process.

Forsyth knows the factory like the back of his hand; he’s been working there since his early teen years, at first sweeping the floors and “trying to be helpful without getting hurt,” his stepdad says with a laugh. “There’s nothing here I don’t know how to do,” Forsyth adds. As if on cue, a quilting machine jams; Forsyth takes over the machine, helping the 16-year-veteran seamstress sort out the problem.

Seeing Stars

With all the manufacturing done in house, it is easy for Gardner to repair mattresses and craft custom products. In fact, when U2 needed bedding for the jet the band leased for its “U2 360°” tour, they turned to Gardner to retrofit a mattress. As a result, Forsyth went where many U2 fans would love to go—on the band’s private jet. He met the plane at Logan Airport to take measurements, then delivered and installed the mattresses at Hanscom Field, likely bringing some relief to lead singer Bono, who suffers from back pain.

Bono isn’t the only one who sleeps on a Gardner mattress; Donald Trump has several on his private jet as well, and Sisk says that most of the radio and TV personalities in the area are currently sleeping on or have slept on Gardner mattresses in the past. “They may not be able to promote it because of commitments to their employers, but they shop here.”

While much of their custom business caters to athletes and other extra-tall clients who need special-size beds, the company also gets the occasional order for round beds, as well as custom orders for yachts, small cruise ship lines, the Coast Guard, and area fire stations, which have maintained peculiar size requirements over time. Beyond sizing, Gardner is mulling a return to offering historic materials, such as striped ticking fabric and horse hair, which has excellent wicking characteristics and breathes well, offering a cooler bed in summer and a warmer one in winter.

While most of Gardner’s business is in New England, the company regularly ships to Bermuda and the West Coast, and, occasionally, to Hawaii, London, and Costa Rica.

The Road to Restful Sleep

Shipping is the primary headache for Gardner these days. “Salem doesn’t have any main roads,” Sisk says. “It’s hard to get in and out of here.” Getting materials in and shipping mattresses out is slowed by Salem’s congestion. Combine that with the growth of Salem State University, across the street from the factory, and a move may be unavoidable. If the factory does move, Sisk plans to keep the business in the area, but closer to routes 128 and 93.

For a company that relies on word of mouth for 85 to 90 percent of sales, though, Sisk says central Salem is hard to beat. “Our location is phenomenal—we’ve been doing business in the same building for almost 80 years, and our customers know how to find us.” Multigenerational customers aren’t unusual, with the children and grandchildren of past Gardner customers continuing to buy bedding locally.

“People don’t always realize how good our bedding is and what a piece of junk the other one is,” Sisk says. “What they will realize is how well they’ve been treated. They can’t go wrong buying from us because we…make sure they are happy.”

Mattress Mindset In the market for a new mattress? The best tip might be to shop Gardner Mattress, joke owner Gardner Sisk and manager Kirk Forsyth, but here are some other things to keep in mind.

- Skip Shopping the Internet Especially if you sleep on your side. If you’re a side sleeper, says Forsyth, you definitely have to go to a store and lie down on the bed.

- Ask What’s Inside “Most salespeople have no idea what’s inside their mattress, and they don’t even pretend to,” Sisk says. “People really want to know about the quality of the materials.”

- Consider Firmness Firmness is not a measure of whether or not a mattress will sag over time. “What breaks down in a mattress isn’t the springs—it’s what you put over the springs,” Forsyth says. “Springs have nothing to do with what’s going to wear out.”