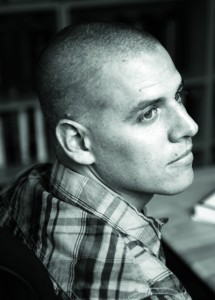

Once a non-believer, a “saved” Matt Chewning brings his new brand of gospel to Beverly. By Bryan McGonigle, Photographs by Mark Ostow

“I feel at home, man,” Matt Chewning says, smiling and taking in the hot North Shore summer air, the afternoon traffic in downtown Beverly rolling by. The 28-year-old is a long way from North Carolina, from where he moved with his wife and kids to start a new venture. It wasn’t a job transfer, though. It was the call of God. Chewning has traveled a long road in his 28 years, from a humble upbringing as a self-described “Jersey punk” to a Southern corporate climber to an impassioned leader of an Evangelical church he is planting on Massachusetts’s not-so-religious North Shore. “Out here, you get all these preconceived notions,” Chewning says, his relaxed Southern drawl contrasting with the rushed, Boston-accented conversations around him. “Christians shouldn’t have sex, Christians shouldn’t drink, or do this or that. Nah, that’s not it. People know what the churches are against, but what are the churches for? So we came here thinking we should let people know what we’re for.”

Genesis of a Jersey Punk

Devotion wasn’t always his thing. Chewning grew up in Woodbridge, New Jersey, a middle-class town south of Newark. His parents divorced when he was four, his pregnant mother turning from a stay-at-home mom into a single mother of two with no college degree or income.

“I remember summers when my mom would be at work, and I would be at home with my brother,” Chewning says. “For extra cash, I would go around to some of the stay-at-home mothers in the apartment building we were living in and take their trash to the main dumpster for a dollar.”

Tough times got a little better. His mother got a job as an office manager in a dental office and eventually married a police officer, while his father thrived in his career at MassMutual Financial Group. Aside from what Chewning calls the typical bickering of divorced parents, things were relatively normal and stable for him and his brother.

But at the age of 17, Chewning learned that stability could be fleeting. He arrived home from school one day to find that his brother was missing. Chewning and his mother looked for him for hours, until they received a phone call from Child Protective Services, saying they had taken him from school and were sending him to live with their father in New York.

“There was some verbal and emotional abuse going on at the house from my stepdad,” Chewning says. His stepfather was a police officer in one of the roughest areas of New Jersey and hadn’t had any children of his own. “Although he loved us, it was difficult for him to deal with us in a different way than the teenage drug dealers he was used to.”

Despite trouble at home, and despite being a “Jersey punk,” Chewning managed to stay out of any major trouble. “I partied a little and chased girls, smoked some weed from time to time, but nothing more than what a typical 17-year-old kid finds himself involved in during his high school years,” he says. In those days, Chewning found salvation in basketball. The basketball court was his church, the hoop his altar, the cheering crowds his congregation. He played ball every day and describes himself as a “gym rat.” He also feels his talent on the court was God given and protected him from the fate of so many of his childhood friends-lack of direction, prison, even death.

Saved on a Gurney

One week, Chewning’s father took him up the East Coast, from New Jersey to Maine, to visit colleges. One college, Eastern Nazarene in Quincy, stood out. After his tour of the school, the admissions officer sat him down and told him, bluntly and unequivocally, that he didn’t think it was the right school for Chewning. It was a strict, fundamental Christian school with a zero-tolerance policy for the usual college fun. This took Chewning aback, who was quite non-religious and free-spirited. Chewning remembers that conversation vividly. “[The admissions director] said, ‘They’re going to make you go to chapel three days a week, you’ll never be able to have girls in your room, and if you’re caught drinking, smoking, or partying, you’re gone.'” But Chewning was fine with that.

Chewning isn’t sure why decided to go to Eastern Nazarene. His mother was Jewish and non-practicing. His father was a non-practicing Catholic. Religion had never played a role in his life or worldview. The only kind of religious discussion Chewning recalls is when he tried to wear a cross around his neck to school (a fashion trend, not a spiritual proclamation) and his mother made him wear a Star of David with it-but that had less to do with his faith and more to do with divorced parent territorialism. His church attendance was limited to an occasional Christmas or Easter Mass with his grandparents.

“I did literally get dragged out of a church basketball league in New Jersey because I kept dropping the f-bomb and didn’t understand why they didn’t like that,” Chewning says.

But there he was, a student at Eastern Nazarene College, where the academic realm was just a little more conservative than Pat Robertson. After just two weeks, Chewning was already calling his dad to “get me the hell out” of there. He says the people seemed crazy; grown men sang to God, praying to a deity he didn’t believe was listening, and everyone on campus talked about Chewning as needing to be saved.

“All I was thinking was I needed to be saved from these crazy people,” he says.

Chewning eventually befriended one of those “crazy people,” a basketball player named Ricky who was non-judgmental, not aggressively preachy, and who would play a major role in the moment of Chewning’s Christian conversion. One day, while the two headed to basketball practice, Chewning noticed a painful lump in his groin. The boys’ coach dropped the pair off at Quincy Memorial Hospital so Chewning could be checked out. A doctor ran several tests and asked alarming questions about Chewning’s sexual history. Anxious, Chewning began to pray. This was unusual for him-in fact, Ricky offered to pray for him while he was with the doctor and Chewning simply thanked him dismissively. But here Chewning was, praying for answers, and, ultimately, for God to reveal himself.

“In that moment, it was like I knew God’s presence was there,” Chewning recalls. “I instantly had an overwhelming feeling of love, comfort, peace. I didn’t see an angel, the hospital didn’t shake or fill with smoke, there was no blinding light or anything crazy. I just knew that God was there with me. It was a feeling that I had never felt before, and it was surreal.”

The doctor then told him everything was fine, probably just a virus passing through his body. Relieved, Chewning returned to the waiting room to find Ricky asleep. He woke his friend, asking Ricky what it meant to be saved. An amazed Ricky reported that, in his sleep, he dreamed that Chewning would ask him that very question, and that he knew he should have an answer ready for him.

Ricky explained what being “saved” meant to him: man is naturally prone to sin and rebellion against God and, unlike typical Christian church attendance and the desire to be good, those who are “saved” believe that Jesus has already done the work and that people should follow Christ because they can, not because they have to. This new point of view, along with his doctor’s office epiphany, dramatically changed Chewning, who had expected religion to be about obeying rules.

“I thought a Christian was someone who didn’t drink, smoke, or have sex before they were married, who didn’t listen to bad music or watch R-rated movies, and who went to church on occasion because that made God happy,” Chewning said. “I had no idea how far that belief system was from the biblical truth and that we could know God through Christ alone and not fundamental legalism. That was brand new to me. Rather than trying to earn a relationship with God by trying to do all of the right things, instead I could know God solely on the basis of what Christ has done and believing in him.”

From that night on, Chewning’s life would be set on a new course of spirituality and religious devotion.

Fruitfully Multiplying

His relationship with Jesus wasn’t the only meaningful one Chewning found in college. It was at Eastern Nazarene that he also met a girl, Beth, who would become his wife. Beth was from Warwick, New York, a New York City suburb not unlike the New Jersey town in which Chewning was raised. Beth grew up just 30 minutes away from where Chewning’s father lived, and they were introduced by mutual friends. Matt was a freshman and Beth was a sophomore. But all was not blissful at first. Beth was not all that impressed with Matt or his personality.

His relationship with Jesus wasn’t the only meaningful one Chewning found in college. It was at Eastern Nazarene that he also met a girl, Beth, who would become his wife. Beth was from Warwick, New York, a New York City suburb not unlike the New Jersey town in which Chewning was raised. Beth grew up just 30 minutes away from where Chewning’s father lived, and they were introduced by mutual friends. Matt was a freshman and Beth was a sophomore. But all was not blissful at first. Beth was not all that impressed with Matt or his personality.

“I really didn’t like him romantically, or even much as a friend, for that matter,” Beth says. “When I first met Matt, he was very vulgar and rude and [would] just say what was on his mind, no matter if it hurt someone or not.”

But one night, that all changed. The same night Matt had his revelation at the hospital and became a Christian, he went back to the campus from the hospital and started telling people, including Beth, what had happened.

“It was really cool to see such a transformation in someone,” Beth said. “Because of our mutual friends, we hung out and he literally became a different person. We became best friends quickly, and, obviously, that turned to more.”

The two dated for three years and then took a leap of faith and got married, when Matt was 20. They had their first child when Matt was in his senior year in college. He was also captain of the school’s basketball team and working 40 hours a week.

“Balancing being a husband, then a new dad, with basketball and work, I think, ‘How did I manage?'” Chewning says, adding that his faith and having a strong partner in Beth were key.

The couple would eventually have four children-Daniel, Abby, Ella, and Jacob-and both say that while most young marriages don’t last, theirs has only grown stronger as they’ve matured through their twenties. “Man, I love her to pieces,” Chewning says of his wife. “I definitely married the right girl.”

After college, Chewning began working in Boston for Humanscale, which specializes in workspace ergonomics and helping organizations to create healthy work environments. Two years later, with their family growing, Matt and Beth decided to move to Greensboro, North Carolina, where the cost of living was much lower and where they could buy a new home for significantly less than they were paying monthly for rent in the Boston area. Matt got a job with a different ergonomics company and climbed the corporate ladder, earning a six-figure income by age 25.

But corporate life didn’t fulfill him. He and Beth saw things they liked in a local ministry. They felt like God was lighting a fire inside them to propel them to do more. So Matt decided to launch his own church.

Casting the Net

Planting a church is not to be done haphazardly; about 80 percent of new churches fail in their first year. So Chewning planned carefully and used his corporate networking skills in his new quest. He joined a church-planting network out of Seattle called Acts 29, which specializes in training pastors and assessing their ability to start churches. They tested him in theology, doctrine, and leadership ability and examined the strength and virtue of his marriage. Eventually, Acts 29 suggested he serve as an intern with an existing church to become more adept at ministry. So Matt served as an intern at 1.21 Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, an Evangelical church referencing first-century teachings in 21st-century life.

Planting a church is not to be done haphazardly; about 80 percent of new churches fail in their first year. So Chewning planned carefully and used his corporate networking skills in his new quest. He joined a church-planting network out of Seattle called Acts 29, which specializes in training pastors and assessing their ability to start churches. They tested him in theology, doctrine, and leadership ability and examined the strength and virtue of his marriage. Eventually, Acts 29 suggested he serve as an intern with an existing church to become more adept at ministry. So Matt served as an intern at 1.21 Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, an Evangelical church referencing first-century teachings in 21st-century life.

The Chewnings would not stay in North Carolina, though. Their sights were set on the North. It was in Boston where Matt found Eastern Nazarene and transcended into his faith and where he met his wife, so that same location seemed right for his next venture. Although a little apprehensive at first, his wife ultimately agreed.

“It wasn’t like he sprung this idea on me out of nowhere,” Beth says. “I was excited to come here because it is where I felt God leading our family as well. But, naturally, as a mother, I was anxious for my kids. I wanted to make sure we were in a good area, that the school systems were good, etc. That was the only anxiety I had. I knew we could make a home anywhere. As long as our family was together, we could make any location a home.”

Thus, Netcast Church was conceived. The name Netcast is derived from the Book of Matthew, Chapter 4, in which Peter the Apostle is casting his net to catch fish. Jesus walks by and says, “Follow me, and I’ll make you fishers of men.” Chewning aims to be like early Christian church founders and cast a net to gather those who haven’t found Christ, rather than just setting up a church for those who already have.

The name Netcast is also meant to capture Boston’s thriving technology culture. Chewning wants his church to be relevant in the high-tech age: he spreads his message via Facebook and Twitter and blogs on the church’s sleek Web site.

Dan Milette has been the pastor at Danvers Church of the Nazarene for three years and has gotten to know the Chewnings in recent months, even providing Matt guidance when asked.

Milette says one of the biggest challenges Matt will face is the location. When Milette and his wife, Rebekah, planted a church years ago, they did so in Kansas City. Out here, Milette says, it’s a whole different environment.

“There are challenges to patience, when you want to just get going, but you can’t,” Milette says. “You have to build a core around you, a leadership core. It’s really a gift that God gives to special people, and you have to find those people.”

Milette has also advised Chewning that before he can preach, he must build friendships and trust, which poses its own set of challenges. That’s where the patience comes in.

“It’s all about relationships. That’s the way it’s set up,” Milette says. “It’s about having a personal relationship with God. We do the same thing. It’s got to be about relationships. When people know that you love them and care about them, you earn the right to be heard.”

Gospel According to Matt

Matt Chewning is definitely eager to be heard. After a couple years of planning, the Chewnings packed up and hit the road. It  wouldn’t be an easy road, though. Finding housing proved to be a nightmare. They spent months looking for a home they could afford. After seeing a Craigslist ad for a house to rent, Matt drove up to the North Shore to check it out, but another tenant beat the Chewnings to it. The only other house, on Pierce Street in Beverly, was in deplorable condition.

wouldn’t be an easy road, though. Finding housing proved to be a nightmare. They spent months looking for a home they could afford. After seeing a Craigslist ad for a house to rent, Matt drove up to the North Shore to check it out, but another tenant beat the Chewnings to it. The only other house, on Pierce Street in Beverly, was in deplorable condition.

Most people might take this as a sign of bad luck, but Matt calls it a revelation of God’s work. They ended up staying in Massachusetts for nine days instead of the planned three. Eventually, the owners of the unsanitary house took such a liking to the Chewnings that they agreed to gut and renovate the place, ripping up the floors, installing a Jacuzzi tub, gutting the kitchen-renovating the whole place. They offered the Chewnings reduced rent and even threw in utilities.

When recalling this sudden turn of events, Matt references a story in which Jesus feeds 500 people, telling them they only return to Him because of their physical hunger, not their spiritual. Matt feels that for them to only turn to God because they are hungry and want something would be like the 500 people turning to Jesus when they wanted to eat. By struggling and going through despair, Matt said, they were able to connect with God without expecting things in return, with nothing to their names but still having their faith, which led to their fortunate outcome.

“Isn’t that something?” Matt says. “The lesson for us is that God was calling us to live here. He gets us to the point where God is enough, and then He throws in bread.”

Netcast doesn’t have a church building. Instead, Chewning holds services at the downtown Beverly YMCA on Sundays at 10:30 a.m. According to Milette, this is nothing out of the ordinary for church plants.

“I’d say 90 percent of all new church plants don’t have a building,” Milette says. “There’s not a base of givers yet. It’s a vision, it’s a dream, an aspiration.” In fact, facing financial crisis a few years ago, Milette’s church sold off most of its land. It now has no mortgage and no debt.

While he hopes to have a house of worship some day, Chewning is content at the YMCA. He practices responsive preaching-connecting with the community and engaging people in discussion about God. He feels that basing a church on a piece of real estate would corrupt his mission and lead him to focus sermons on raising money to pay for it all. He wants the church to be about a message, not a building.

“We believe that Jesus is our hero; He is God and historically, He lived perfectly, then He died and He rose,” Matt says, his Jersey roots glimmering through with a slight hint of Newark swagger. “So if all that’s true, then it’s not about giving $10 on a Sunday, is it?”