Walking into the Gloucester workshop of cabinetmaker John Cameron is a little like entering a wormhole into his busy, buzzing, creative mind. One wall is papered with detailed pencil sketches of chairs and chests of drawers. Another wall is a patchwork of black-and-white photographs of kelp and stark-looking three branches against a gray sky. A black piano is pushed into a little side nook, and a guitar sits atop a table. The New Orleans blues of Dr. John is reverberating among the tools and in-progress projects as Cameron works. Stacks of leather-bound sketchbooks are filled with notes and ideas and drawings; another one might be tucked in his pocket. His wood block prints and metal engraving tools surround the microscope he uses to create the detailed engravings that embellish his work. A book will likely be sitting on his desk, too. Today, it’s Freya Stark’s 1934 travel memoir, The Valley of the Assassins and Other Persian Travels, which, like all books, Cameron reads “for how it’s written, how sentences are constructed, how a book feels.”

The same description could be applied to his work, which marries beautiful aesthetics with masterful technique. Each line of each piece of his furniture is deliberate: Cameron wants a viewer’s eyes to travel across a piece a certain way, whether it’s sweeping along the concave shelves of an open cabinet or traveling to the center of a Japanese-inspired screen to focus on the wood’s burl pattern. No detail is too small. Cameron remembers staring at one of his student pieces for days, trying to figure out what was wrong with it, before realizing one of its edges was slightly too sharp.

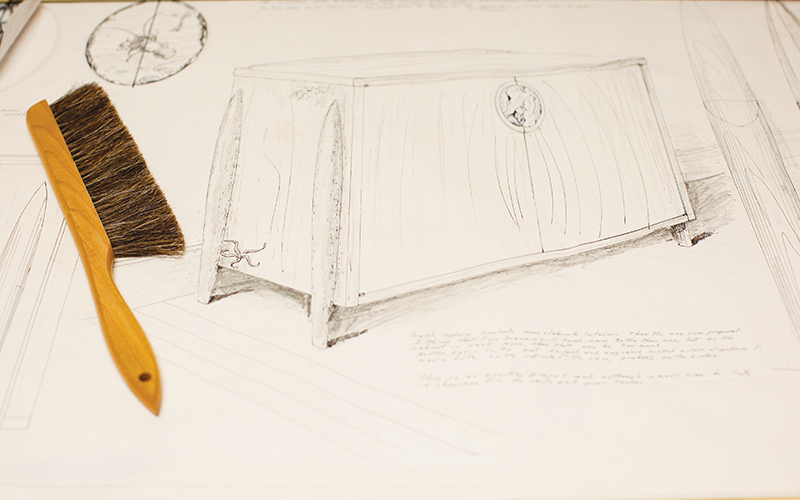

“Well-crafted pieces that aren’t beautiful leave me cold,” he says, peering through a pair of round metal glasses that he picked up in a junk shop somewhere, probably 25 years ago, he guesses. His fingernails are stained brown, thanks to the natural shellac he applies by hand to his works, eschewing sprayed polyurethane varnish or lacquer because he thinks it looks “plastic-y.” Working by hand extends to other parts of Cameron’s creative process, too, like using wooden hand planes that he made himself and drawing rough pencil sketches on paper before executing a piece.

“People respond to hand drawings,” he says. “You can go anywhere and get a lovely CAD drawing, but there’re no smudges on it.” There’s no sign of the hand and mind that created it.

|

For the past nine years, Cameron has worked in Gloucester, where he also lives, designing and creating a variety of commissioned and spec pieces. They range from works like the Ming Dynasty-inspired Crane Chairs with fluidly curving black splats that comfortably flex as they’re leaned into; to a headboard with a “crazy burl veneer of walnut” embellishing its center; to an Art Deco-influenced custom cabinet made from wood that he describes as “a symphony in reds” adorned with an escutcheon plate that’s hand engraved with a kelp vignette.

Despite his decades of work in furniture building, Cameron’s creative life didn’t begin in a workshop. It began at the piano. He attended Berklee College of Music at a time when “nobody wanted to admit they went to music school,” he says. He found a passion for songwriting, and got gigs in local bands. Having always loved building, too, though, he also found work in that trade, first as a boat builders’ apprentice in Salem and then as a bench work apprentice at a furniture shop in Cambridge.

Then, “the band I was in finally started to take off,” he says. That band was Bim Skala Bim, the well-respected (and still active) Boston Ska-rock band, with which he spent years playing and touring the United States and the world, all the while harboring that love of designing and building.

“I was still woodworking like crazy in my basement,” he says, until he saw a new American furniture exhibition at the Museum of Fine Arts that blew him away, opening his eyes to what ambitious, modern furniture could look like.

“I needed a starting point. And what a beautiful starting point,” he says. “It really inspired me.”

So Cameron took a hiatus from the band to attend the esteemed Fine Woodworking Program at the College of the Redwoods in Northern California. There, he and his classmates worked so feverishly and with such excitement and passion that they barely went home at all, regularly working late into the night, long after the workshop had closed. The two years he spent at the school took his work to a new level.

“I thought I knew how to do things, like sharpen tools,” he says. “No. I didn’t know how to do anything. I just rolled over like a puppy.”

After returning home from California, Cameron went back to Bim Skala Bim and played with the band for another five years before joining the Fort Point Cabinetmakers co-op in Boston. He worked there for 11 years, while playing with the band at night, until finally moving to Gloucester, reasoning, “let’s see if I can find a place to be on my own.”

At first, he spent most of his time doing run-of-the-mill projects like kitchens and build-ins, which left little time for creating his own, more nontraditional designs. It’s a conflict that many creatives face: Finding a balance between the work that pays the bills and the creative work that feeds the soul.

“I was about to give up on the chasing rainbows thing, when I got a call and got invited to join the New Hampshire Furniture Masters,” he says. “Now, I’m building things I love and believe in.”

Membership in the prestigious group has opened many doors for Cameron, and today, his work is shown in places like the Smithsonian Craft Show, the Fuller Craft Museum, and exhibitions in London and Bath via the United Kingdom-based Society of Wood Engravers. Cameron’s custom-made commissions and spec pieces are highly in demand around the country, and his designs get more detailed and ambitious year after year.

“I’m trying to bring beauty into the world,” he says. “I trust my eye more than I ever did.” johncameroncabinetmaker.com

Cameron’s workshop is festooned with drawings, books, and works in progress

Cameron’s workshop is festooned with drawings, books, and works in progress