Fitz Henry Lane (a.k.a. Fitz Hugh Lane) secured his place in American art history as a marine painter of high regard. Yet before he became a full fledged painter, he was a highly skilled printmaker, and it’s this foundational aspect of his career which is the focus of Drawn from Nature & on Stone, at the Cape Ann Museum in Gloucester. The exhibition consists of 59 artworks. Guest curator Georgia Barnhill believes his narrative in lithography “really pulls together the whole artistic maturity.”

Lithography was a game changer during the 1820s in America. A hybrid art, part artistic and part mechanical in reproduction, lithography enabled artists to render reality with an accuracy never seen before. Printmaking challenged traditional painting’s uniqueness because it was reproducible. Suddenly artist and artisan joined hands in the creation. Art became collaborative—and commercial. For the first time, graphic art could put its products in the marketplace and in the hands of buyers in large numbers. The democratization of the image forever changed art’s accessibility.

View in Boston Harbour, c.1837.

Lane was a native son of Gloucester, born Nathaniel Rogers Lane in December 1804. He changed his name to Fitz Henry Lane officially at age 27. What’s more, over time, he became known willy-nilly as Fitz Hugh Lane until historians cleared up the mistake in 2005. The museum will share a handout titled, “Fitz Who Lane?” if requested. Motives aside, he signed his works F. H. Lane, so the mystery remains.

In 1832 Lane left Gloucester, filled with artistic longing and a natural talent for drawing. He joined other working-class young men as an apprentice at Pendleton’s Lithography in Boston. There, he honed his skills, no doubt taught the fine points by mentors with whom he worked. From this time, two early lithographs show a novice artist trying to make his mark. In separate sentimental scenes he drew young girls at play, each clinging to her own pet in a pastoral setting, perhaps designed for hanging in a child’s room.

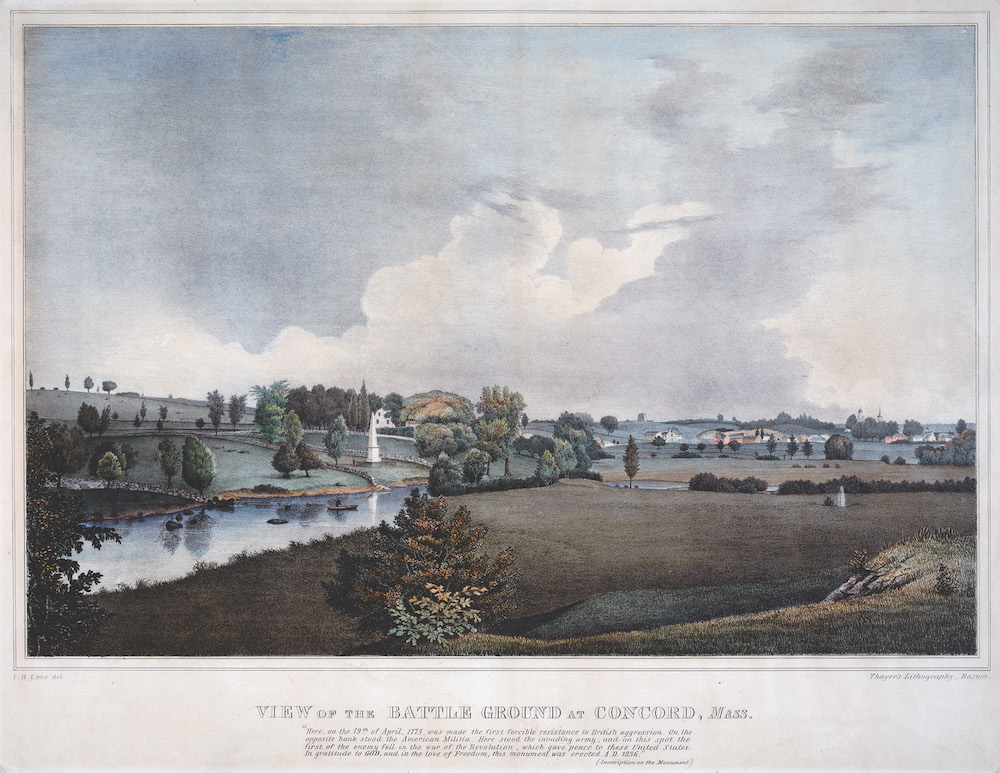

View of the Battle Ground at Concord, Mass., 1840.

Outstanding in his lithographs—and later his paintings—is an overwhelming attention to fine detail. Lane’s View of the Town of Gloucester (1836) appears as an almost photographic rendering, down to individual leaves on trees and shrubbery, window panes on houses, lines of ships’ rigging, and miniature human figures performing everyday tasks. It’s as if Lane was foreshadowing the advent of photography, which emerged in France and England around the same time.

As Americans prospered and leisure was attainable, music became an important part of family life. In many households, the piano replaced the hearth as the gathering place. Sheet music was in great demand, and lithographs started appearing on its covers to draw attention and boost sales. Illustrations had to reflect the music’s content, of course, but also arouse curiosity. Fourteen eye-catching covers present a range of themes, from the patriotic, Salem Mechanick Light Infantry Quick Step, showing soldiers in strident formation standing at attention, to something heart-wrenching in The Maniac, with a shackled inmate locked in a cell, meant to inspire sympathy for the mentally ill. By contrast, The Pesky Serpent: A Pathetic Ballad portrays a husband offering a dangling serpent to his startled wife, who teeters in horror before a fiery hearth. The intent is lighthearted and farcical.

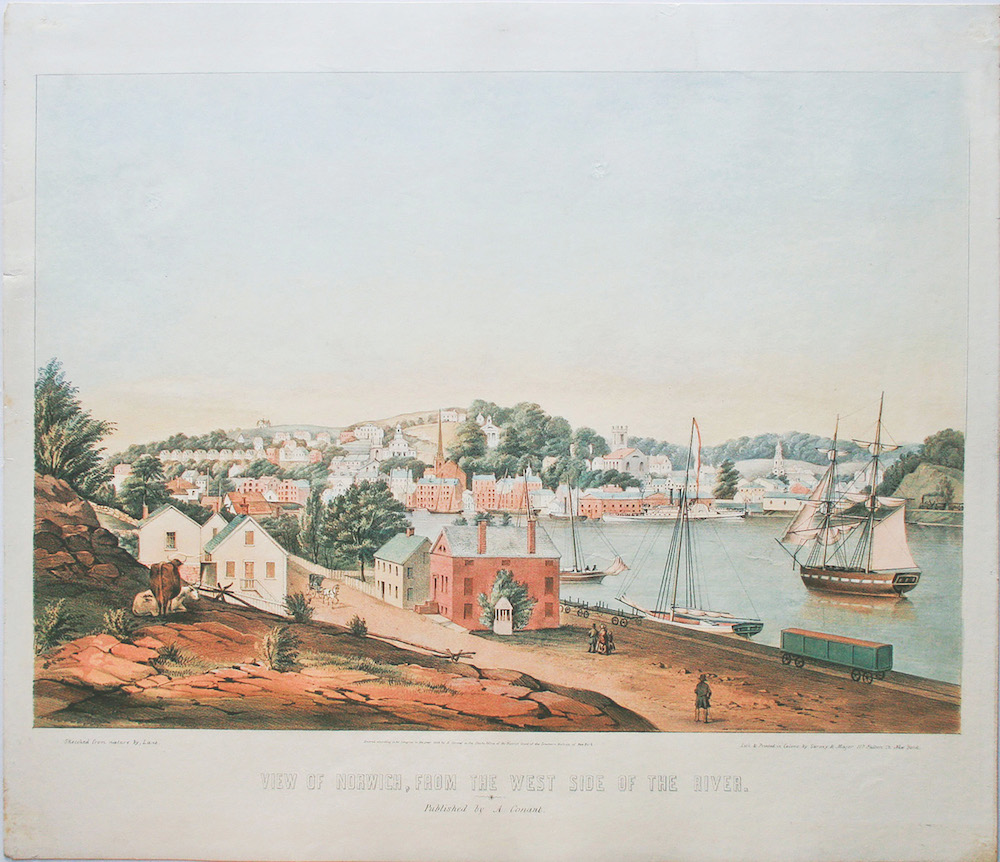

View of Norwich, from the West Side of the River, 1849.

As America earned its place in the world, civic pride inspired a surge in patriotism. The noble experiment had worked, and now it was time for bragging rights. Lane provided lithographs that reflected a vivid sense of place. Harbor scenes, studies of bustling wharves, architecture, townscapes, and mariner life were all ripe subjects. Now, Gloucester citizens of all stripes could have heretofore impossible views of their beloved town framed and hanging in their homes. As Lane traveled, he expanded his vision, and he chose a variety of places to depict: the battleground at Concord, views of Lowell, New Bedford, Newburyport, and coastal Maine.

Color entered lithography around 1840, either during the printing process, or afterwards, via hand-tinting. The additional tonal ranges dramatically accented the third dimension, with the effect of enhancing the illusion of depth.

Lane experimented with panoramic views. One display sheds light on his methods. His reputation secured a commission by Joseph Stevens Sr., to produce a townscape of Castine, Maine, similar to two he had done of Gloucester. His pencil sketch, Castine from Hospital Island (1855), shows in meticulous detail the initial steps he used to create the final lithograph next to it. For the sketch, he affixed six pieces of paper for the wide-angle view. As stipulated in the commission, “accuracy” was the goal. Not only do you see the fine details of the town’s architecture—homes, commercial buildings, wharves—but also the artist’s notations to himself: “Church;” “This house little high,” “School House.” The words humanize the process and show the artist’s mind at work.

Lane returned to Gloucester in 1849 as a renowned painter and lithographer. He built a house of granite at Duncan’s Point overlooking the inner harbor and selected the third floor for his studio. Here he would spend the rest of his days creating in the surroundings he cherished. The house, now owned by the City of Gloucester, has been repurposed for other uses. Anchored nearby is a large bronze statue of Lane by another Gloucester artist, Alfred Duca, as well as his bronzed Birkenstock sandals mounted on a granite slab. The inscription reads: “Step into my shoes and become inspired.”

Eventually, Lane’s oil paintings outshone his lithographs, and over time the latter were neglected. Barnhill says, “We seldom have a record of an artist’s development. For Lane, we have the whole story. When the story of an artist like Lane is known, then it informs the careers of other artists as well.”

Cape Ann Museum

27 Pleasant St., Gloucester, 978-283-0455