Maybe you remember that old organ in grandma’s parlor. Flipping an orange switch sent electricity humming through the circuits, and rows of yellowed keys made odd, discordant noises. Well, this is not your granny’s parlor organ.

On an industrial road four miles west of Gloucester Harbor sits the C.B. Fisk building, where designers and artisans build massive pipe organs like Bach or Haydn might have played. The instruments can reach more than four stories high and are built in the great mechanical action traditions of pre-20th-century organ builders. Instead of having electronically controlled pipes, each key pulls a carbon fiber track that releases air into handcrafted wood-and-metal pipes. The pipes themselves are designed to the exact scale and style of Old World Europe’s finest organs, and the resulting sounds are as rich and nuanced as the originals.

“You get warmer, more pungent qualities out of pipes that are scaled generously, and there are certain sounds associated with the period that the music was written for,” says Michael Kraft, C.B. Fisk’s president and senior reed voicer. “We use pipe scales from the golden ages of organ building. And over five decades, we’ve built projects that delve into many styles, from Italian Renaissance to 20th-century symphony halls.”

The late Charles Brenton Fisk founded C.B. Fisk, Inc., in 1961. With degrees from Harvard and Stanford, Fisk planned to become a nuclear physicist, and he was a technician on the Manhattan Project. But he took up organ building at Stanford and made a name for himself by rejecting the industry’s move toward modern electro-pneumatic instruments. Only in a mechanical action organ—with a hand-pumped wind supply—could such an impossibly complex machine “seem to be alive,” he wrote. “You hear it breathing.”

Today, C.B. Fisk custom builds mechanical action pipe organs for churches and institutions around the world. The company’s designers travel across Europe to research centuries-old organs and musical traditions and incorporate design elements into new organs. And while most clients request electric blowers to maintain a steady wind supply, there are exceptions.

Opus 72, for example, was built for Wellesley College’s Houghton Chapel and installed in 1981. Its design was inspired by the 17th-century Jakobi Church organ in Germany and Esaias Compenius organ in Copenhagen and features 1,845 hand-sculpted pipes. True to Fisk’s purist roots, the instrument has an optional human-powered wind supply. As the organist plays, operators step on large treadles, which open the upper leaves of the bellows (like fireplace bellows, but bigger). This draws air into the organ’s lungs, which is then exhaled through the pipes. Opus 72 is considered one of the world’s great pipe organs, and in the hands of a skilled player, it can recreate 17th-century German music as if the composers were playing their own tunes.

“It’s the sort of organ that teaches you how to use your hands and feet in very intimate ways,” says Margaret Angelini, carillon instructor at Wellesley College. “That’s partially because of the mechanical action and partially because of the wind, which is flexible like a singer’s wind. You have to listen deeply for the wind, and if you listen that way, the organ is phenomenally expressive.”

Angelini is a Wellesley alumna who matriculated there in the fall of 1981, the same year Opus 72 was installed. She learned to play on the famed organ and later earned her master’s degree in organ performance from the New England Conservatory of Music. But Houghton Chapel’s organ was in the works long before Angelini arrived on campus. The late Wellesley professor of music Owen Jander joined Charles Fisk on a research trip to Europe in the mid-1970s. The result of their fieldwork is an instrument whose sound would be instantly recognized by 17th-century masters such as Dieterich Buxtehude and Heinrich Scheidemann.

“A lot of that music is still being discovered on that organ in this chapel,” says Angelini. “It’s an amazing experience.”

Most C.B. Fisk clients request organs that draw from several historical periods, posing both a structural and tonal design challenge. That was the case with Opus 120, considered the company’s magnum opus. Installed at the Lausanne Cathedral in Switzerland in 2003, the 7,000-pipe organ combined baroque, classic, and romantic styles from France and Germany. It was also the first American-built pipe organ installed in a European cathedral, a job that was massive in size and scope. In all, Pike and his fellow organ builders spent 48,000 shop hours on the project, collaborating with Swiss architects, Italian designers, Canadian wood workers, British computer experts, and German pipe makers.

Voicing the organ—the process of manipulating the pipes to fit the acoustics of the space where it is installed—is a months-long process. C.B. Fisk’s voicing teams work in shifts, playing and adjusting the organ until it sings as it should. The Lausanne Cathedral’s acoustics were “luxurious,” according to David Pike, the company’s senior vice president and tonal director. The larger challenge was finding a tonal harmony incorporating the instrument’s many historical sounds.

“The art is to figure out how to combine these diverse elements into a single instrument and have it make sense musically,” says Pike.

Building a C.B. Fisk organ is both simple and infinitely complex, and the process can take several years. Inside the shop last November, designers and artisans were putting the finishing touches on Opus 147, a 3,707-pipe organ built for the new Holy Name of Jesus Cathedral in Raleigh, North Carolina. The Raleigh community dedicated the 44,000-square-foot cathedral in July 2017, and it features seating for more than 2,000 people. With a cruciform design and a 160-foot-tall dome on the building, the Archdiocese of Raleigh envisioned an equally impressive instrument.

“Music is transformative, and the majestic quality of the pipe organ assists people in understanding an encounter with the Lord,” says Monsignor David Brockman, vicar general of the Diocese of Raleigh and the chair of the cathedral’s organ committee.

The seeds of that transformative experience began in 2014, in meetings between C.B. Fisk’s designers and the cathedral’s architects, acoustic consultants, and organ committee. The organ needed to re-create the original Roman Catholic liturgies, so the C.B. Fisk team drew inspiration from 19th-century English Romantic organs. The instrument also had to fit seamlessly into the cathedral’s sprawling space, and its tonal design had to consider the church’s construction materials, volume, layout, and even its climate.

“You have to be sure you have the tonal resources to fill the space with sound, and that comes down to scaling the pipes and the materials from which they’re made,” says Pike.

With those designs in place, the organ builders created a 1:16 scale model of the cathedral and fit a model of the organ into the space. (Dozens of similar models are displayed around the design studio, a pantheon of Fisk organs from across the decades.) Then, the company’s 25 engineers, woodworkers, pipe makers, leatherworkers, and musicians set about bringing their vision to life.

The organ’s casework and interior structure were constructed from raw lumber, which was planed and sawn at the shop. Because the instrument is so large, its various sections were assembled separately across the building’s rooms, like layers of a cake. In the entryway sat the organ’s upper reaches, and its intricate keyboard and first tier sat at the rear of the building.

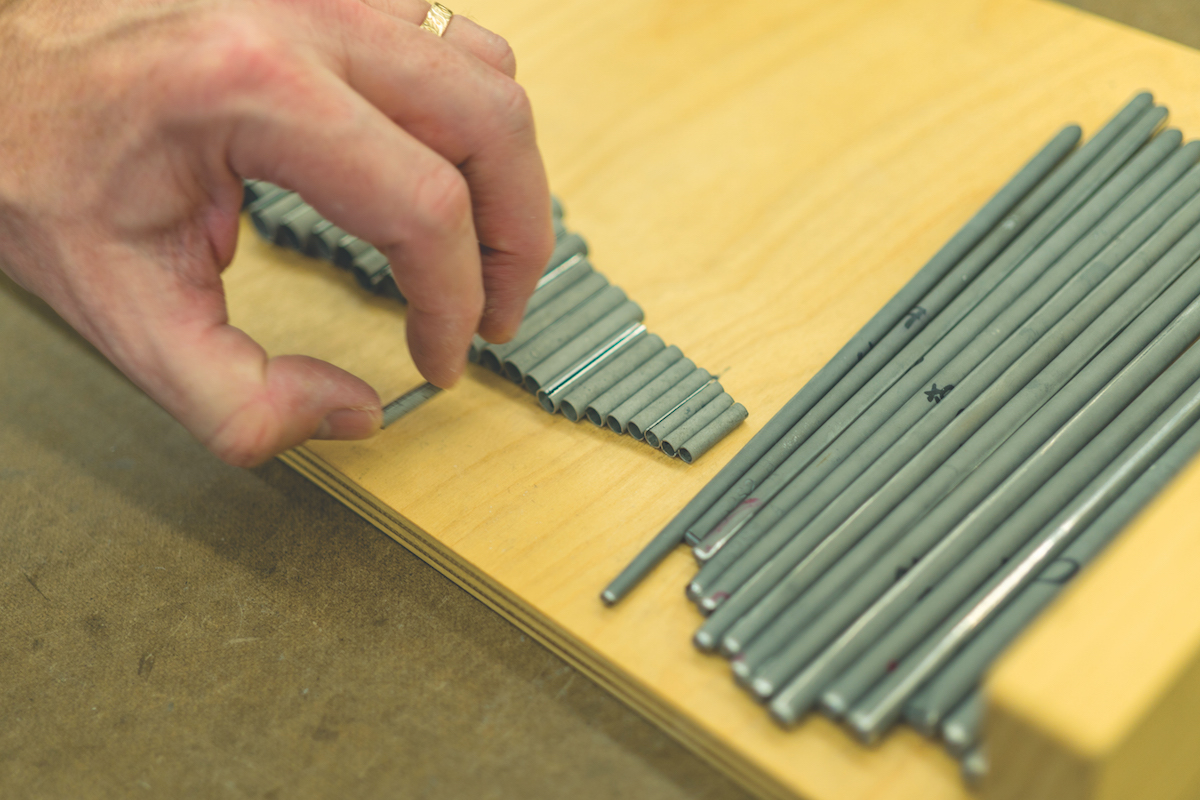

The pipes for Opus 147 were made of wood and sheets of tin and lead, which were alloyed at the shop, and then cut, soldered, and filed to precise specifications. The smallest pipes are just ¾ inch long and the largest are 32 feet.

Emily Pardoe, a 2007 graduate of Beverly’s Montserrat College of Art, has been with C.B. Fisk for 10 years. The 32-year-old specializes in building organ bellows using wood and leather, and she has taken on the role of assistant voicer at C.B. Fisk. In 2014, she spent several weeks in Niiza, Japan, as part of the voicing team for Opus 141. And at the Holy Name of Jesus Cathedral in Raleigh, she hopes to again join the voicers in bringing Fisk’s latest masterpiece and the great composers to life.

“To be able to actually hear and feel that in a room is very powerful,” says Pardoe. “It’s inspiring.” cbfisk.com