On a Sunday morning last fall, I took on a simple task: Lead Jasper by his reins through the woods as leaves crunch underfoot. Keep him focused. Breathe.

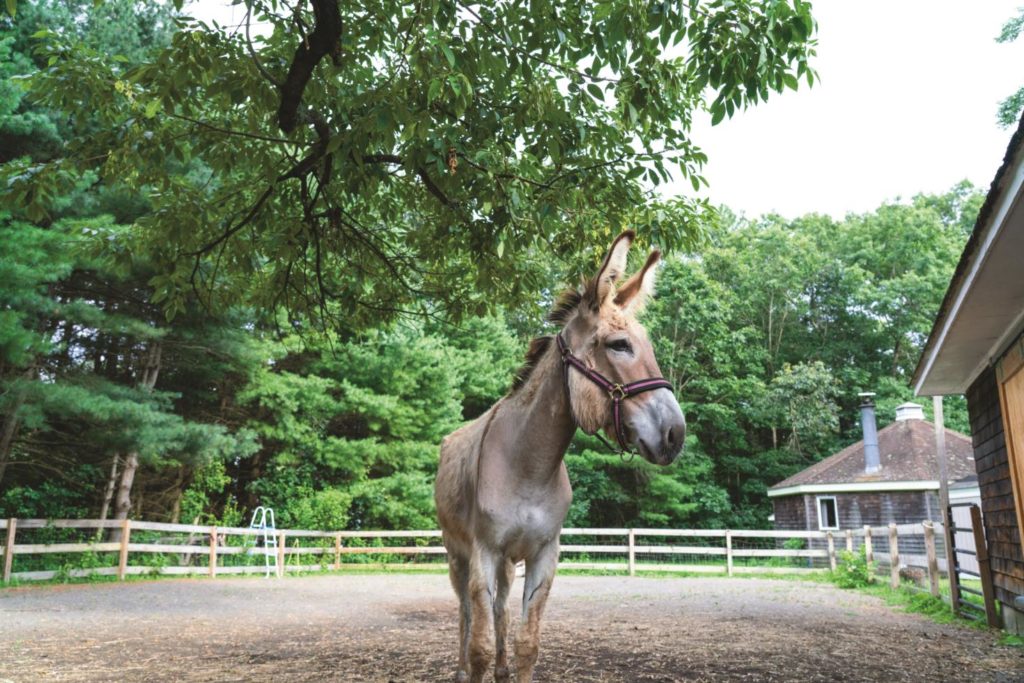

Jasper is a four-year-old gray donkey, a rescue who arrived on the North Shore angry and bedraggled from a Texas kill shelter two years ago, and who is now more like a large dog, eating peppermint treats out of my hand. Jasper and a black miniature horse named Romeo, who now greets the elderly in nursing homes, were saved from a gruesome fate thanks to the Equine Rescue Network, an organization formed in 2009 here on the North Shore.

The two animals now live—along with other twitchy ears, long, batting eyelashes, and round bellies covered in grays, black, and tans—in a paddock at an expansive North Shore farm, where a Sunday ritual invites volunteers of all stripes to walk these once-mistreated creatures through woods and green pastures, soothing them along the way.

“If you’re an animal in 2019, I feel sorry for you. We’re not an animal-friendly society anymore,” says Janine Jacques, who started the Equine Rescue Network at her family farm in Ipswich.

In order to save these animals, Jacques says she is fighting against China’s cosmetics industry. Donkey hides go for big money to be ground into women’s face cream, prompting the Chinese to consume 1.4 million donkeys a year, says Jacques. A cube of a donkey’s hide is worth more than a cube of gold, she says. “They are consuming the world’s donkey population.”

When I recently spoke to Jacques on the phone at her day job as a dean at the New England College of Business, she had received a text message that two donkeys had just been loaded up in a Texas kill pen to travel to their rescuers in Kentucky, Virginia, and Massachusetts. She will pay $250 to $350 per donkey. “I sit in my office in Boston or in line at Starbucks receiving photos of these animals from the shippers,” she says. “Then I electronically send the money for them.”

Every year, Jacques celebrates her birthday by going to a big auction in Pennsylvania and saving animals. But not all can be saved. Some have slipped through her fingers. A two-year-old colt with burrs in its mane, a horse that had never been touched, still haunts her. The trailer was full of rescues and she simply couldn’t take another, and he was bought by one of the kill buyers. “I can’t get his face out of my head,” she says of the colt, as we lead a pack of recovering horses, mini horses, and donkeys from a big pasture to the gravel road leading back to the stables.

Each year, Olympic trials are held on the farm here for dressage and hunter/jumper classic categories. You wouldn’t expect to find a bunch of damaged animals being boarded here, but it is possible through the kindness of the farm’s owners, says Jacques.

Ann Getchell, whose family owns the farm, has been surprised at how much she loves the donkeys. She has adopted three gray donkeys with big cross-shaped markings on their backs. “I’m kind of a sucker for these,” says Getchell. “We have all this family property. I can’t think of anything else my mother would have wanted up there in the barn.”

Probably because I’ve been paying more attention, I’ve noticed an uptick in donkeys and talk of donkeys in the area. A local marathoner now takes a tiny donkey, appropriately named Dash, on long runs in Bradley Palmer State Park. Anytime you see a donkey on the North Shore, it probably came through the Equine Rescue Network, which saves up to 200 donkeys and big mules a year—and then there are the horses.

While a scared horse will run, says Jacques, a frightened donkey will stand still. “It makes all the difference in the world. Donkeys think through processes.” Many are now familiar with donkeys as aids in conflict resolution, when a group who can’t get along must work together to try to budge the animal. “People think donkeys are stubborn,” says Jacques. “They aren’t at all, but when you get in a hurry and your energy changes, they say, ‘No. I’m not moving.’ You can’t get anxious. Be confident, and then a donkey will do anything.”

Jacques grew up riding competitively, and rescue horses were her family’s passion. “I don’t know if I’d know what to do on a horse that knows what to do,” she says while brushing Renegade, a rescued Amish driving horse who wasn’t up for the task of steering families in carriages on busy highways. The horse was in rough shape when he arrived, but he is now prepping to do the very posh annual hunt at Appleton Farms on Thanksgiving. Jacques’s quirky family even started a little traveling circus at one point, doing tricks on horses.

Her mother runs the Service Dog Project in Ipswich, raising dozens and dozens of Great Danes to help people with mobility issues. Jacques has written three books on rescue animals, including the recent Make Way for Donkeys, a true story of two donkeys saved from a terrible fate and sent to Colorado, where they became pack burro racing donkeys. The titles of the other two books will make you want to devote your life to her cause: Dogs, Donkeys & Circus Performers: Hilarious Stories of Animal Adventures on a Path to Making the World a Better Place for All Creatures Big, Small, Four & Two Legged and Lost Horses: A Guide for Horse Lovers to Make a Difference.

Of course, there are opportunities to benefit humans, too. Suzanne MacPhail is a licensed mental health counselor certified in equine therapy who works with Cultivate Care Farms in Bolton. The farm-based mental health and wellness practice has recently expanded to Ipswich. “Horses and donkeys feel energy, and they know what’s going on right when you go into the ring,” says MacPhail. She goes on to explain how they can help patients who are healing from trauma, depression, grief, loss, substance abuse, and eating disorders. “The animals break down walls and make people vulnerable.”

This treatment is covered by five kinds of insurance. Patients can get into the ring and tell their stories of trauma while hanging out with the animals. The idea is that we process emotions and thoughts best during activities and interactions. In addition, MacPhail recently brought her Cambridge College students, who are studying to be psychotherapists, to the farm to help them learn to manage self-care by spending time with the animals, which reduces burnout from caring for patients.

Also among the volunteers today is Amy Cyr, who manages the dog and cat practice at Danvers Animal Hospital; she enjoys leading the bigger animals on Sundays, especially after having back surgery last spring. “It’s beautiful. It makes sure I get out and walk every Sunday. It gives me donkey, horse, and mule time.”

Meanwhile, at another farm, one of the rescue network’s animals is living the life. Looking like a tiny unicorn, the gleaming white miniature horse puts her head through the fence to crunch a NECCO wafer almost the same shade of pink as her muzzle. “Not too much sugar, Clementine. You are getting chubby,” says Claudia Von Gumppenberg, the owner of this magical creature.

Not much larger than a big dog, Clementine lives on Emerald Hill Farm in Essex, a 17-acre horse farm that looks across an expanse of pristine conservation land. Clementine is lucky to be here, where she has a job calming the expensive show horses. At one time Clementine’s future was bleak. Claudia received a picture of the horse just in time and made a split-second decision to save the animal’s life. Two years later, Von Gumppenberg asked her husband if they could get another, and Casper came into their lives the same way. The couple enjoys watching their big mare, Chelsea, protectively stand over little Clementine as she lies in the sun. When Von Gumppenberg bought the farm and spruced up its stalls and barns in 2011, she never dreamed the mini horses would grab her heart. “This farm is a serene and quiet setting. We gave them a second chance at life. But they give back to the farm, too.”

I attended a fundraiser for the Equine Rescue Network at the Service Dog Project with the Great Danes. Donkeys big and small ran free around us. They ran in clumsy packs, eliciting laughter from the crowd, many of whom wore T-shirts with various funny donkey slogans on them. A teen with autism petted a few of the gentle creatures as his mother explained their healing qualities.

Jacques has borrowed tricks from her mother’s playbook with the Great Danes by putting cameras on certain donkeys, allowing viewers to get involved with their lives and, in turn, help support her organization. Audiences of more than 5,000 watched Maude give birth. A naming contest followed and made her baby, Pockets, a star on social media.

Salem resident Melanie Tossell had just returned from a trip to Ireland three years ago with “donkeys on the brain.” She and some friends were visiting the farm, where she has worked with horses off and on for years, when she spotted a handsome American Paint donkey off to the side near a group of miniature donkeys. She purchased the donkey from the Equine Rescue Network for $200 and named him Doolin. One difference between donkeys and horses is that donkeys remember, says Tossell. And once they trust, she says, they forgive. In her experience, you can hug a donkey all day and they won’t pull away. “Donkeys are the most loving beings ever,” says Tossell. “They’ll do anything for you. They have a spirit I never knew.” Make no mistake, donkey love is a real thing, she says. “You know they’re happy when they smile. You can rub their big ears and they nestle up. It’s endless.”