For nearly 140 years, horses have shaped the character of the North Shore in profound ways. When equestrian sports like polo and fox hunting arrived in the midst of the Gilded Age, the region became a breeding ground for talent. For decades, the U.S. Equestrian Team trained in South Hamilton. George S. Patton, perhaps Hamilton’s most famous resident, competed on horseback at the 1912 Olympics before earning renown during World War II. And that regional embrace of equestrian life left a gift even for locals who’ve never sat in a saddle: The landscapes set aside for riding are at the core of some 15,000 contiguous acres of open space carved out just miles from Boston.

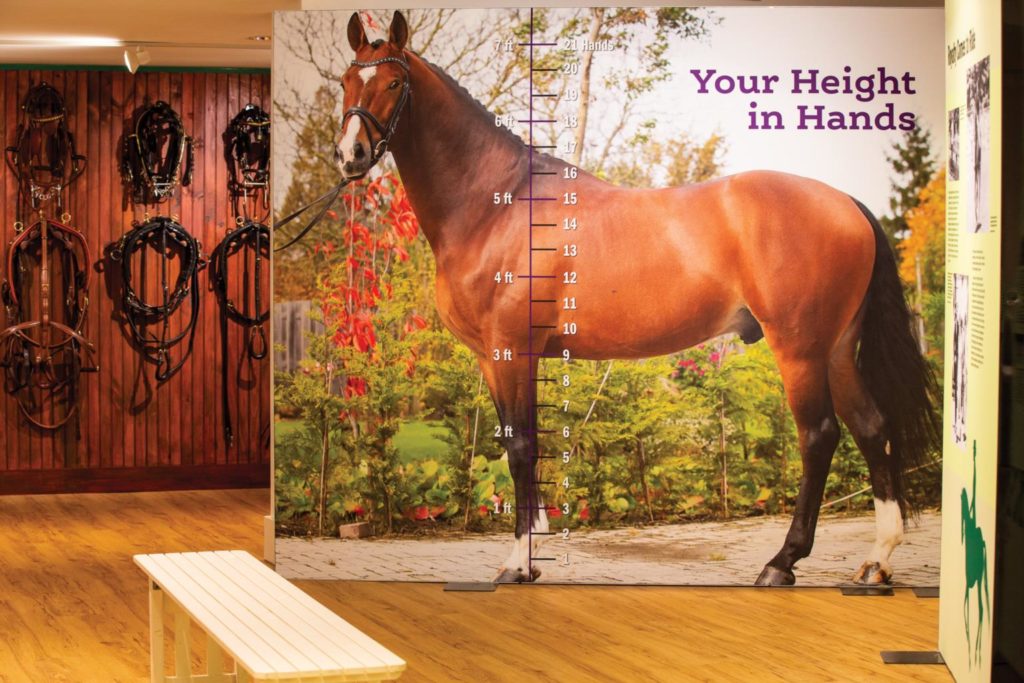

Equestrian Histories, an exhibition at Wenham Museum that opened in June, celebrates this legacy with 1,100 square feet of artifacts, images, and mementos aimed at riders and nonriders alike, offering a glimpse of how equestrian sport has transcended its aristocratic origins and left a lasting influence. “This is part of history,” says Winifred Perkin Gray, chair of the committee that developed the exhibit and a lifelong equestrian. “And it’s not just a part of the history of Wenham; it’s part of the history of the North Shore and New England.”

Beginning in the late 1800s, the North Shore became a destination for leisure-seeking titans of the Gilded Age. They could head north from Boston by train, sail yachts on the North Atlantic, and ride their steeds on the horse farms clustered around the region. Hamilton’s Myopia Hunt Club—a locus of polo and foxhunting—was founded by a member of the Forbes family. Bradley Palmer, who co-founded the United Fruit Company in 1899, rode on a 700-plus-acre estate in Topsfield. And in the wake of the 20th-century housing boom, those pristine acres were natural candidates for land conservation; the trails and carriage paths on Appleton Farms in Ipswich and Bradley Palmer State Park in Topsfield, for example, were initially created for the rigors of riding.

“The equestrian community was involved in preserving trails that are now in use by everybody—people who are out mountain biking, walking their dogs, strolling with their families,” says Kristin Noon, executive director of Wenham Museum. And while groups like the Essex County Trail Association and The Trustees of Reservations have been integral to stewarding those landscapes in the last half century, Noon adds, “It started with equestrians.”

The idea for the exhibit itself, meanwhile, started with Gray, a Wenham resident who fell in love with horses while growing up in Connecticut, trained under elite coaches, and then balanced motherhood and dressage competitions. “The connection with horses is sort of visceral. You’re born with it from an early age, or you aren’t,” Gray says. “And the reason I love dressage so much is that it’s a combination of being highly technical—there are so many nuances, and you’re always learning—but there’s also a wonderful, almost euphoric feeling when you ride a perfect 20-meter circle or a canter pirouette.” Injuries compelled her to give up competing about a decade ago, but she still dotes on Willie, her 32-year-old Hanoverian grand prix horse who saunters around his pasture, “a gentle giant who’s taught me so much,” she says.

After Gray visited Wenham Museum for a lecture in 2016, she had an epiphany: Why not shine a light on the North Shore’s rich equestrian heritage? She proposed the idea to the museum’s leadership, who saw a chance to capture an overlooked, family-friendly facet of the region’s history. Gray picked up the phone and assembled a committee, set to work on fundraising and gathering from a wish list of equine-related mementos, and, after the group hit their fundraising goal last January, commissioned Jeff Kennedy Associates of Somerville to revamp the gallery and design the exhibit.

Equestrian Histories functions as equal parts Equestrian 101 overview of the techniques, vernacular, and backstory of four key equestrian disciplines—polo, foxhunting, three-day eventing (a combination of dressage, cross-country, and show jumping), and combined driving, an updated version of the ancient art of driving a carriage—and in-depth exploration of the riding culture of the North Shore. “We wanted to show the differences between the equestrian disciplines, as well as who these wonderful people were who made it happen here in the first place,” says committee member Holly Pulsifer, an authority on combined driving and author of the book Coaching on the North Shore of Boston. “Who were they? What’s their story?”

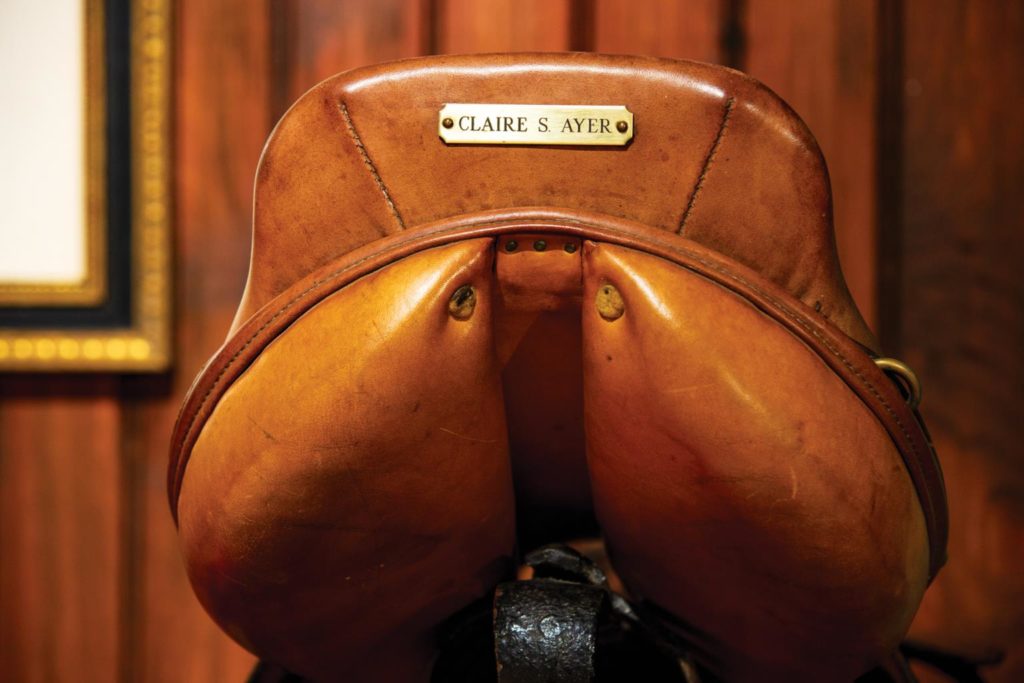

The exhibit features a litany of bridles, reins, halters, and stirrups from the North Shore’s most notable horsemen and women. There’s also a selection of artifacts from the Patton family, including the general’s participation pin, and ultra-rare elements like the King Cyrus Cup, a trophy commemorating a 1970s visit to Iran by Myopia Hunt Club polo players at the Shah’s invitation. There’s even a hands-on children’s section, where they can learn to ride sidesaddle or braid a horse’s tail.

In the process of putting together the exhibition, the committee found meaning in what might have easily become forgotten ephemera. After receiving Gray’s call, Neil Ayer—an erstwhile equestrian whose father developed three-day events at Ledyard Farm in Wenham—sorted through scrapbooks, documents, and dusty archives, emerging with gems like a 16mm reel featuring a steeplechase held in 1927 on Bradley Palmer’s property, storyboards from The Thomas Crown Affair’s polo scenes, and a trove of other pictures and documents captured by his father and grandfather. “To me, it was personally satisfying to be able to share these images and materials in this context,” Ayer says. “A lot of these things wouldn’t have seen the light of day otherwise.”

By design, Equestrian Histories is an evolving exhibit. Noon says the museum intends to add a slate of programming and launch a second iteration of the exhibit in spring, right in time for the dawn of another equestrian season. In part, that reflects the desire to delve into aspects of equestrian life crowded out by space constraints on the exhibit. But it’s also necessary, since equestrian life on the North Shore, while not the force it was in the 19th century, isn’t firmly in the past. Myopia Hunt Club, for instance, hosts open-to-the-public events throughout the summer as well as a popular Thanksgiving Day hunt (where riders chase a bottle of scent, rather than a live animal) departing from Appleton Farms.

No matter how much time elapses, equestrian sports are a fixture of the North Shore. “There are many senses of tradition in the area, and equestrian is one of them,” Ayer says. “People admire it as a touchstone of the past. Yet it’s also something with a pageantry and a form to it that’s happening right now.” wenhammuseum.org