If you’ve sampled any beer native to the North Shore, chances good that Andrew Bablo has influenced the can’s design or his art has graced a wall at the brewery to make your tasting experience more colorful.

Pretty much everything Bablo touches, with his particular aesthetic and marketing savvy, turns to gold. He spun his senior thesis project at Montserrat College of Art into the international niche magazine Steez, about skateboard and snowboard culture, which published quarterly for nearly a decade. This led to a lifestyle of traveling to Los Angeles to meet with advertisers like Vans shoes, hanging out with professional snowboarders, doing celebrity interviews with public figures like of literary god Dave Eggers, and featuring in his very own magazine DJ Jazzy Jeff and Wu-Tang Clan.

“It was like a big party scene,” says Bablo, as he shows me around his Beverly studio. “You had artists, bands, these concepts and ideas, and you got a real feel for what this demographic is into. And there I was, just a designer, meeting with these big companies at 23 years old.”

Bablo had subscribers and a print run of more than 20,000 copies per issue. He had freelancers covering everything from EDM (electronic dance music) in Los Angeles to metal concerts on the East Coast. It was like 156 pages of pure love poem to bro culture and to the cool ladies who fit into the culture. All 35 of the thick, weighty issues of Steez magazine took up to 50 staffers and freelancers to produce and were distributed in all 50 states and Canada, with limited distribution in Japan, Korea, and some parts of Europe. Then, Steeze became a sought after sports apparel brand.

Today, still at just 33 years old, Bablo is inspiring and in possession of an enviable career. He calls himself a “risk taker,” which seems an understatement. He seems to view himself and the art world with the right amount of light-heartedness. He’s an artist with a big career that he manages by taking on projects that challenge him, and he is booked months in advance for logos, murals, signage, and packaging. He will design a coffee table, a beer tap handle or the entire concept of the new restaurant you’re opening. His look is big, bold, and full of swirling color with the industrial mark of its maker. Coming from a blue-collar town in upstate New York, Bablo also loves the playful side of life and of art, that is not fancy or exclusive or taken too seriously.

“I love it when people can experience art,” he says. “When there isn’t too much of a barrier. I want people to touch it and feel it and experience it. That’s why I like murals. They’re community oriented.”

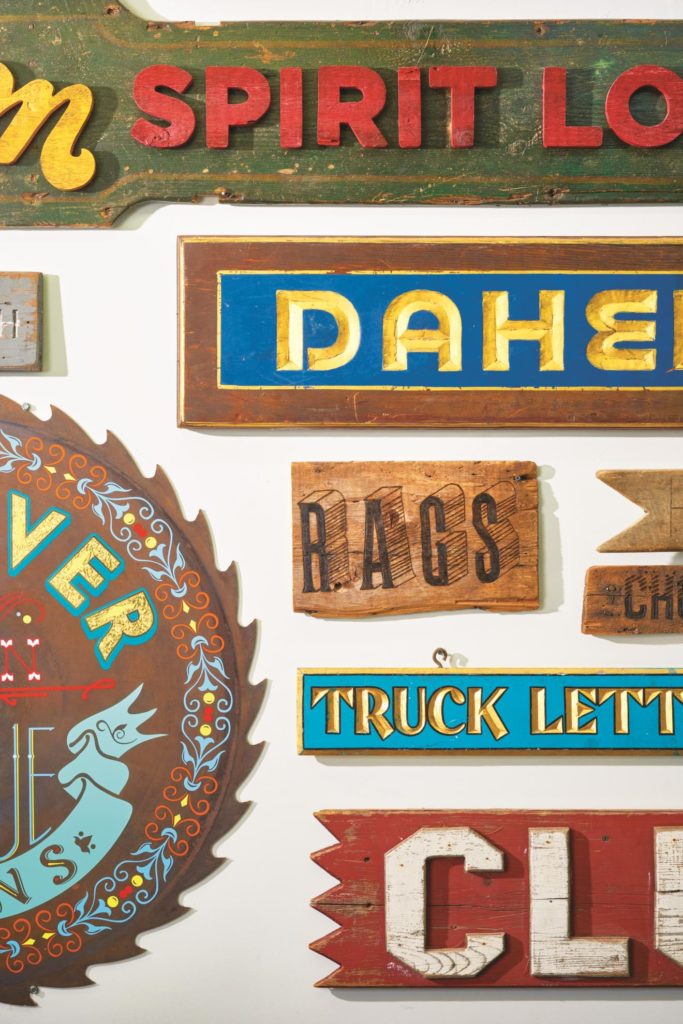

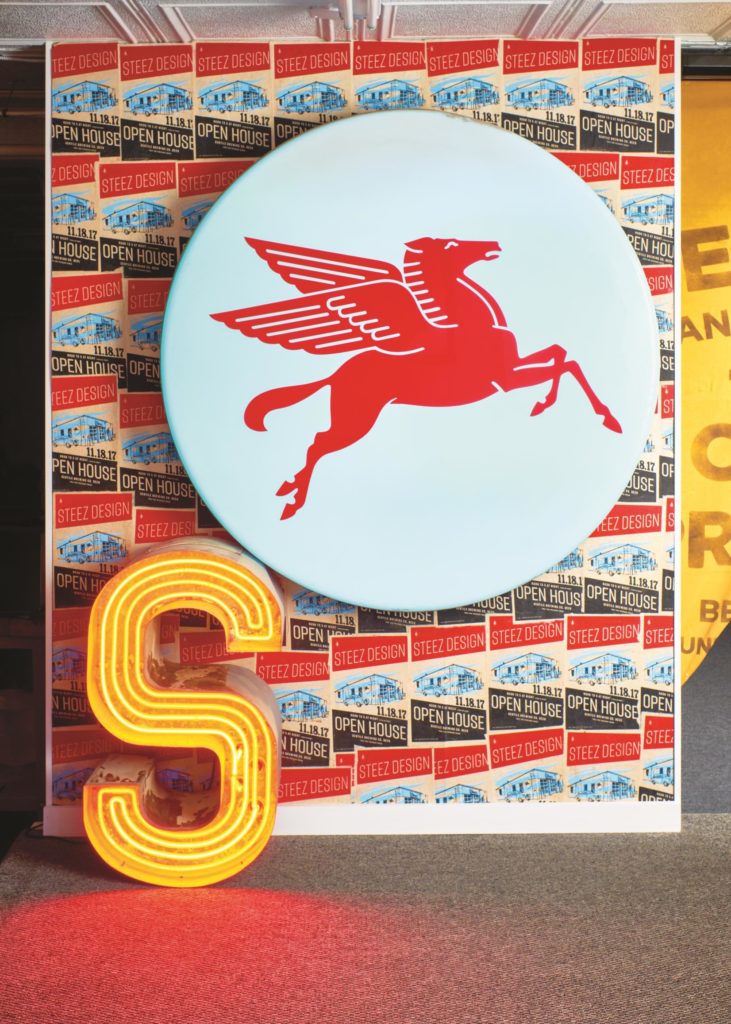

This community lifestyle has led Bablo to stay put after graduating from Montserrat; he’s lived in downtown Beverly for 15 years, watching it grow into a more arts-minded city. His girlfriend’s art studio and shop is conveniently located a few blocks down Cabot Street from the Steez studio, an underground space of whimsy that could be described as the man-cave of a tinkering genius. Individual meticulously organized spaces are arranged where he can follow his various creative pursuits. There is his desk that still bears the editor-in-chief sign, but also an epic long table for graphic design projects, a wall of colorful rolls of vinyl, a massive vintage neon gas station sign that he’s refitted with LEDs, a 1951 lime-green retro fridge that he refurbished, a wall of wheat-pasted posters that suggests his interest in feature walls in interior design projects and, beyond a plastic curtain, his woodshop.

Pretty much all the men in his family, including his father, were in construction. “I learned how to use tools quite young,” says Bablo. Which must be why he gives off that vibe that screams: he’s super handy and good at problem solving, and that he can repair, jigger, or upcycle anything.

This interest—bordering on obsession—in making art more accessible comes from childhood when he wanted to touch everything everywhere he went and being told no. “I want people who wouldn’t normally go into galleries to go,” he says. “My parents would ask, ‘Can we go in there?’ and I would say, “of course you can,” he says. It seems Bablo has been saying those same words to himself his whole life.

Each December, Bablo travels to Miami for Art Basel, where he can check in with current design trends, and what other artists are doing and obsess over various materials being used. The giant, sometimes intimidating art fair, doesn’t faze Bablo in the slightest. “These artists are just people like you and me. They don’t know if they’ll even be back here next year.”

Several years ago, Bablo navigated around the red tape of city and state government agencies to paint 3,000 square feet of the Beverly/Salem Bridge, creating blue and white waves on columns underneath the massive structure. He and his partners had to do part of it in the freezing cold of winter in order to qualify for funding. “That’s a minor victory for the arts,” he says, “to break the ice, because the waterfront will be developed one day and we wanted to take that space first.”

He also has a big mural at Bent Water Brewing Company in Lynn, visible from the Lynnway on Route 1A and a 200-foot mural at the Ink Block in Boston. At Ellis Square Social Club on Cabot in Beverly, he created an accent wall from album covers. “I like big visual work,” he says.

In September, he celebrated his biggest project to date, when an old soda fountain he and a friend discovered in Las Vegas was dismantled and reassembled inside a gallery at the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley. It opened, serving hot dogs and ice cream, as a functioning experiential soda fountain. As a nod to the desert from which it came, they brought in six tons of sand. This all came after Bablo completed a two-year project painting the vaulted ceiling of the freshman arts building, donated to the same university by the Guggenheim Foundation. This was a collaboration with Pat Milbery, a former pro snowboarder, who also had his own column in Steez magazine.

One of the reasons Steez stopped publication is that the sport was actually in decline, says Bablo. Looking back on running a magazine that transitioned nicely into Steez design house, Bablo is thrilled that he created a tangible project on deadline for so long. “I’m extremely happy that I did it. I had some of the best days of my life. But eventually, everything turns into a job, right?” Although he is unafraid of hard work, still it seems this is what Bablo is trying to avoid: the creep of complacency and the repetition of life that comes with entering your third decade on the planet. “That’s why I’m all about the idea and the bigger concept,” he says. “If I’ve already done it, what’s the point of doing it again?” steezdesign.com