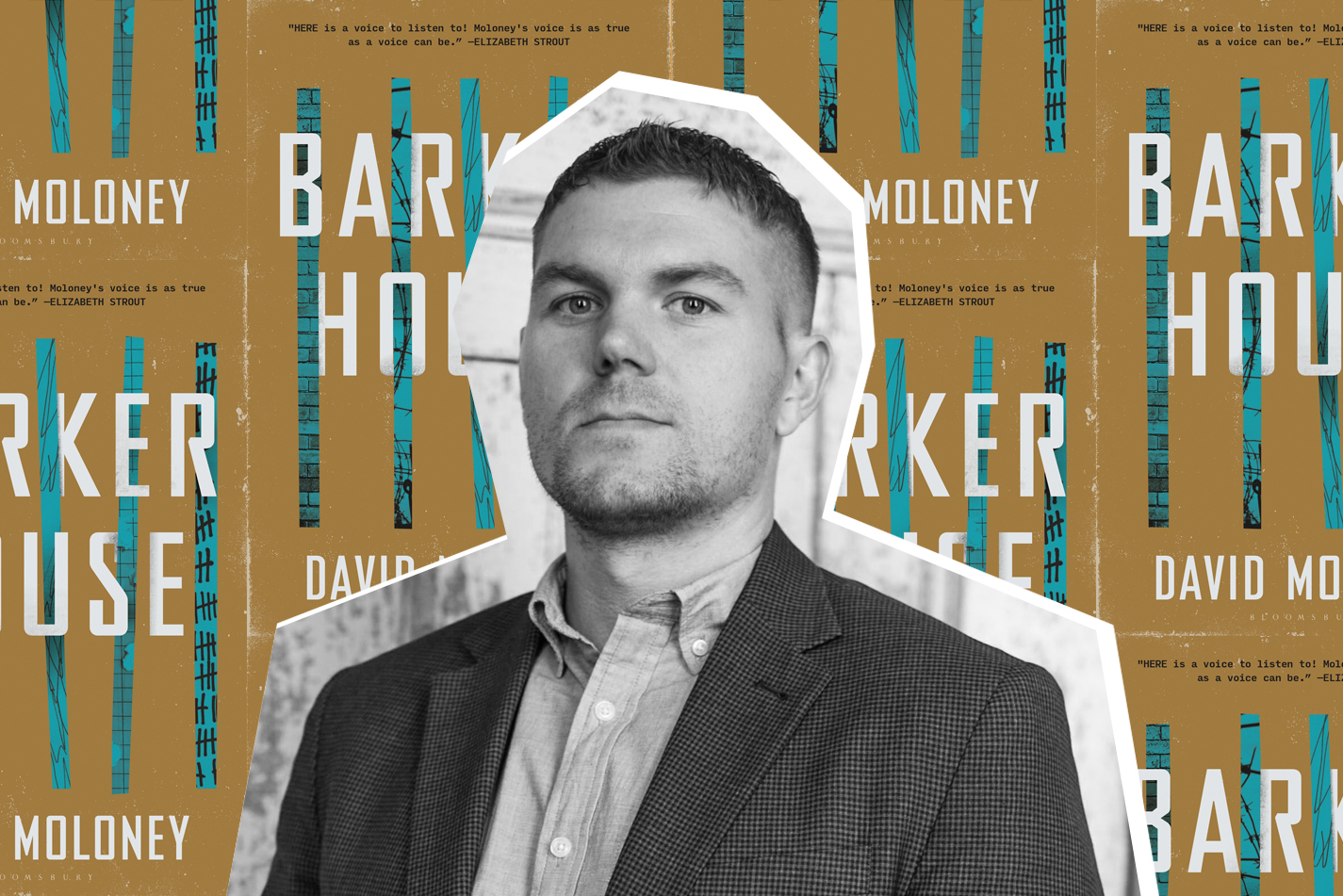

Photograph by debutiful.net.

Chicken wing delivery man. Landscaper. Bartender. Bouncer. And now author. David Moloney’s worked myriad odd jobs but perhaps the most thought-provoking was his time working as a corrections officer in southern New Hampshire, which inspired his first novel. Barker House, a collection of wry, pensive short stories reminiscent of Olive Kitteridge—a collection praised by that book’s Pulitzer Prize–winning writer, no less—was released this spring during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic and swirling tensions over law enforcement.

But for Moloney’s characters, and himself, corrections has a lot of gray area. “I try to show there’s sometimes not that much difference between orange and brown,” he says of prisoners’ jumpsuits and his former uniform. “Some inmates I met were really good people and made a mistake. And some officers do shady stuff and probably shouldn’t be working there. A lot of [inmates] were accused of something they didn’t do, and others were too dangerous to be out in public.”

It’s been almost 10 years since Moloney served on a unit, although he still wakes up exhausted after dreaming of working a shift. The prison guard experience is different from an oft-romanticized view of police officers and prisoners, he says, and there are few fictional portraits of those who watch the incarcerated after the boys in blue are done with them. Serving as just one of two guards assigned to 92 prisoners per unit was one of the reasons Moloney was inspired to portray “what is a completely different environment” than a detective’s or beat cop’s.

The gritty voices of the Beat Generation—Jack Kerouac’s, especially—continue to inspire the fellow Lowell native the same way that they did when Moloney was in high school. Although he went to college at 18 to pursue a creative writing degree, his career trajectory has been as meandering as that of Sal Paradise in On the Road. Moloney left Salem State University after three semesters and got a job working overnights with troubled teens at Tewksbury Hospital.

The bad hours, the patient restraints, and barbed wire on the fence were good preparation for his next job at the prison, he says—a gig that offered better pay and the chance to earn a pension. “But I didn’t like how the job changed me. You see in the book how these characters and officers go through a lot and don’t want to talk about it after work, so they just shut down and wall themselves off. That was true about me.”

The best words of advice he got were from a veteran sergeant. “He was just like, ‘What are you doing here? Get the hell out, don’t end up like me.’ That made me think,” says Moloney, who got a variety of odd jobs and went back to school at 26 with plans for a degree to teach high school English.

Those plans changed when he met professor and author Andre Dubus III at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, where Moloney got more life-altering advice to pursue his unique voice. “‘You’ve got to do an MFA and keep this writing thing going,’” Moloney says of encouragement from Dubus. “But I didn’t even know what an MFA was then—that wasn’t part of my plan.”

Going to classes and workshops weekends, nights, and online to pursue a master’s degree in fine arts yielded Barker House—a panoply of voices from corrections officers and the banter of cell mates Ray and Don, who provide rays of sunshine in some dark times. Each chapter captures the accent of the Merrimack Valley, with distinct affect and intonation, along with local landmarks whose names have been altered.

“As a reader, I appreciate dialogue that’s worth it, that feels real, and I work hard on it,” says Moloney. “I’m Irish Catholic, so I’m quiet most of the time, I sit and listen to the way people speak. It’s almost like eavesdropping.”

Barker House’s punchy snippets are a far cry from the long-winded diatribes officer Scott O’Brien gave in Moloney’s original 200-page manuscript. “I was reading a lot of Faulkner and getting really into writing these monologues,” explains Moloney. “Andre was like, ‘You can’t keep doing that.’” Moloney revised most of his work and made O’Brien the subject of a couple of chapters, but added in perspective from rookie guards, a female guard, and other veterans of the system.

While leaving corrections was like “ripping off a Band-Aid” and he’d rather put that time behind him, Moloney does like to write what he knows. His second collection of stories features the Merrimack River as the unifying element and is being pitched by his agent now.

“I’ve always lived a two-minute walk from the river. Lowell has a huge Cambodian population, lots of Greeks, Irish, Portuguese, Brazilian—there’s just so much material to write about,” he says. The new opus features five different parts of the city, portraying the culture and identity of each.

Since the pandemic forced the cancellation of Moloney’s Barker House tour (excluding a few bookstore Zoom get-togethers), he’s hoping to at least get more facetime with readers for his second book. One of the reasons he’s stayed in his hometown is because of a thriving literary culture, including local author days at Pollard Memorial Library. Each writer speaks for 20 minutes, for a seven-hour day filled with socializing and new reads added to his to-do list.

As for now, he’ll be leading pandemic homeschooling for his 5-year-old son and 8-year-old daughter—an avid reader who “basically finishes a book in the car on the drive from the library to home.” Moloney’s other students skew a bit older than the high schoolers he envisioned instructing when he returned to college. Inspired to relay what he learned from Dubus, Moloney counts himself lucky to be a creative writing lecturer at Southern New Hampshire University. The school already had a strong remote-learning program, but expanded online class offerings over the past few months due to the pandemic.

Contact bloomsbury.com.