The Salem Witch Trials continue to be an ongoing source of interest 331 years after they ended, as anyone who’s even passed through Salem can tell you. But they also continue to be a source of news.

Earlier this year, a huge cache of 527 original, handwritten court documents were transferred from the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) to their permanent home at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court archives in Boston. And in 2022, a group of North Andover eighth graders successfully petitioned state legislators to finally exonerate Elizabeth Johnson Jr., making her the last convicted “witch” to be officially cleared of wrongdoing.

Events like these show that the Salem Witch Trials might be history, but they’re still making headlines.

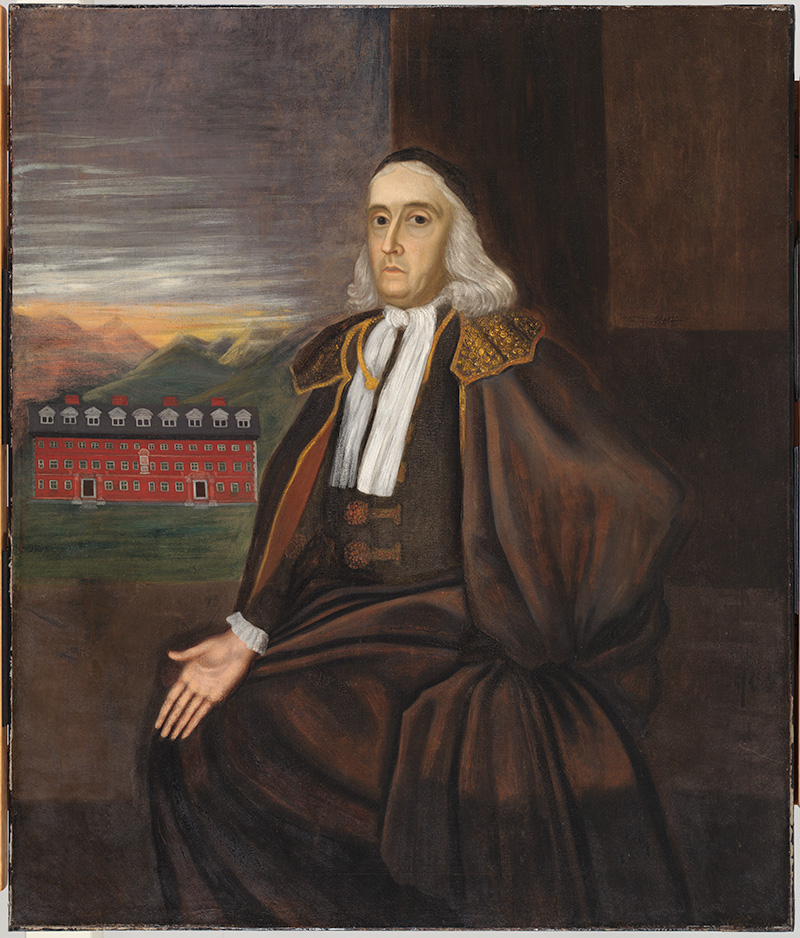

“The Salem Witch Trials are this evergreen subject of fascination for many people. Books come out every year about the trials and the people that were involved in them,” says Dan Lipcan, the director of PEM’s Phillips Library. “Ultimately, the Salem Witch Trials were influential in the development of the freedom of the press, freedom of religion, and freedom of speech because of what happened in the aftermath where people were publishing [critical] material about the Puritan government.”

Now, PEM is hosting a new exhibition called The Salem Witch Trials: Restoring Justice, which examines the trials using court documents, original objects that belonged to the people involved, and pieces of modern art inspired by the trials. It’s on view now through November 26.

The exhibition looks at the witch trial crisis through the lens of restorative justice.

“Restorative justice is really about [asking] what does the victim need? How can we repair the trauma and the harms that have been done to the individual, to the family, and to the community? How do we move forward after something like that?” Lipcan says.

It’s an important question since the Salem Witch Trials “totally split this community,” he says, with neighbors accusing neighbors. The exhibition not only tells the stories of the victims, but also digs into the ways people acted in 1692 and in the years following the trials. For instance, some people spoke out against the injustices as they were happening and petitioned on behalf of their accused neighbors, which was a risky thing to do in a climate where anyone could be accused.

The exhibition also looks at efforts to heal from the injustice after the trials ended, from petitions for restitution payments and official exonerations, to scholars investigating and questioning what happened and why. It also shows how long healing can actually take. After all, Elizabeth Johnson Jr.’s name was officially cleared only in 2022.

“It’s still happening,” Lipcan says. “It took 300 years for Salem to build a memorial to the victims.”

Unlike prior exhibitions, which displayed the original documents, this year’s program displays reproductions.

“What the reproductions allow us to do is enlarge them and light them more brightly because the [original] documents needed to be kept under low light to prevent light damage,” Lipcan says. “We’re hoping that those things mean that it’ll be easier for people to read them and see them.”

The original witch trial papers now reside in Boston at the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court archives.

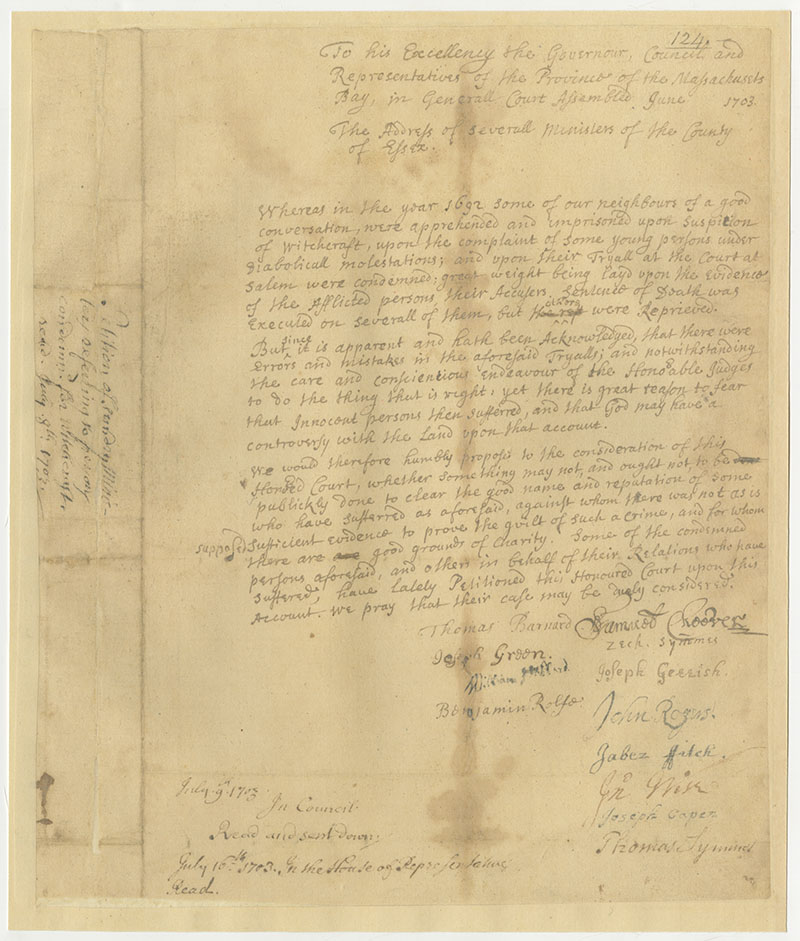

Since 1980, PEM had stored the witch trial papers—which are court documents—on behalf of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court, which owns them but didn’t have a proper storage facility for them. Among the delicate documents are official complaints accusing people of witchcraft, depositions, petitions, and even Bridget Bishop’s death warrant.

Before transferring the documents, though, PEM completed the incredible task of photographing and digitizing them, making them freely available for anyone to see online. Now, because of that work, the documents are more accessible than ever.

“We worked really hard to get all the documents we had in our care photographed in high resolution and put online,” Lipcan says.

It’s just one more way that PEM and the city of Salem are working to broaden our understanding of the Salem Witch Trials, which have been a constant source of wonder and speculation for more than three centuries.

“Maybe part of it is the mystery of it,” Lipcan says. “We can’t know everything about what happened.”