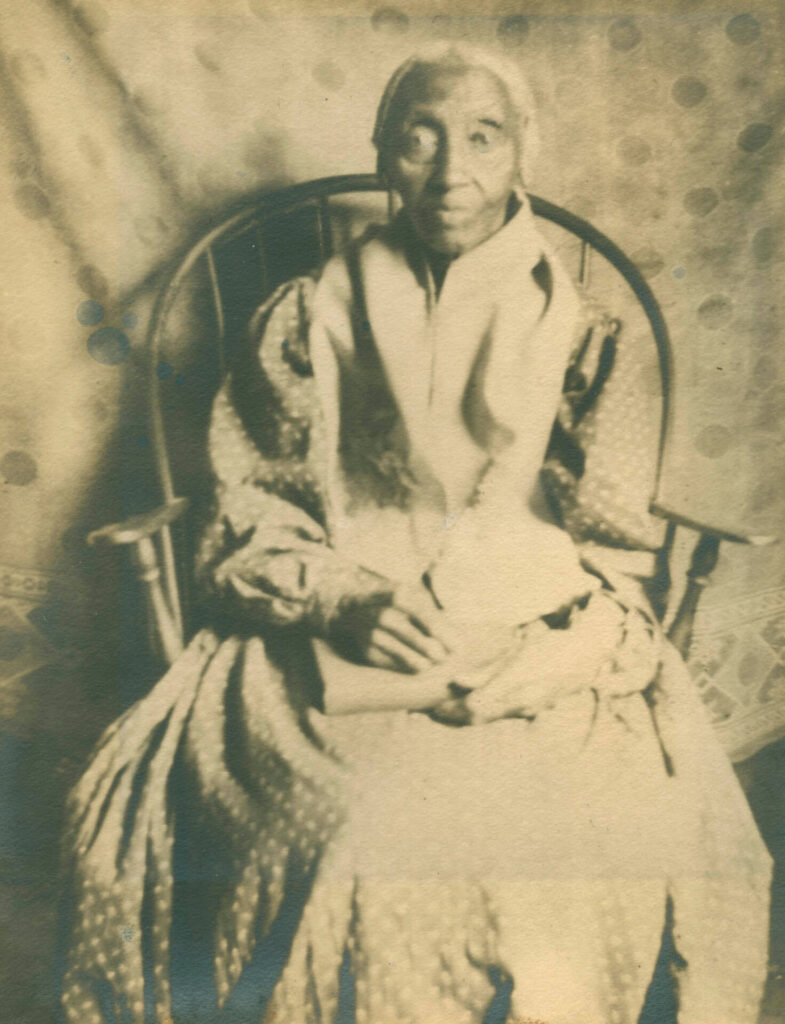

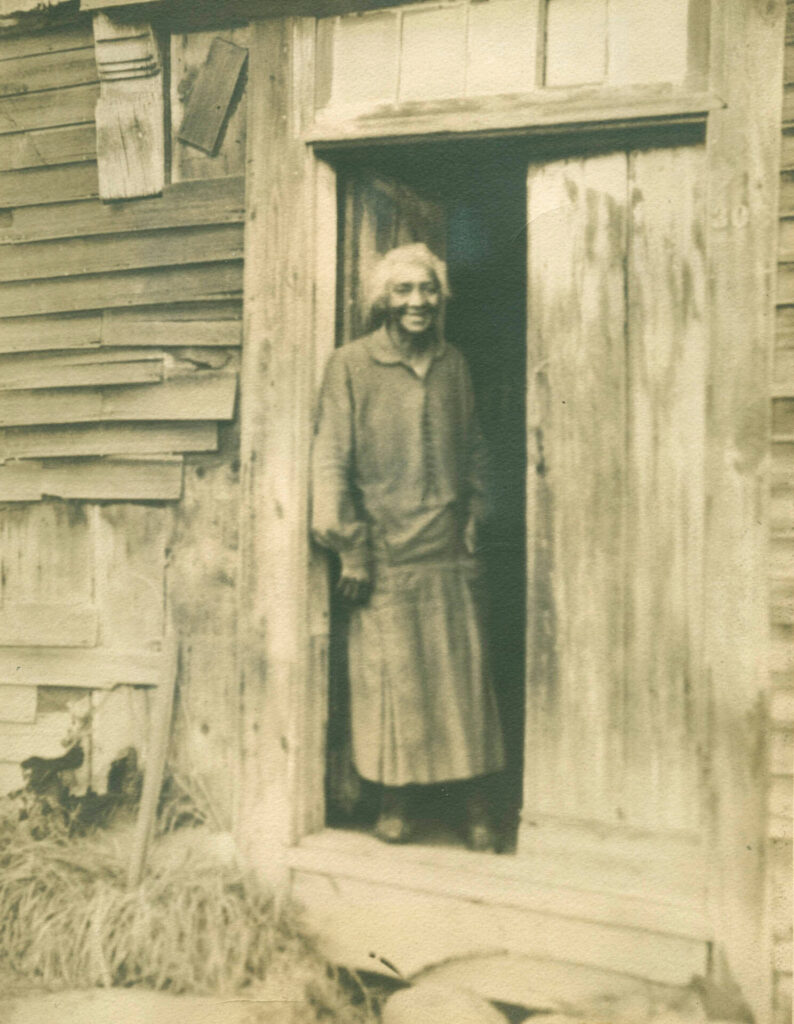

In 1981, housing security nonprofit Wellspring bought a West Gloucester house to serve as its base of operations—and inherited a mystery. In the attic of the building, a traditional, low-ceilinged home built in 1709, the new owners found several photographs. The sepia-toned images included formal portraits and one casual shot of a woman leaning in a doorway. The subjects were all Black people.

Wellspring leaders had heard the lore about the house—that it had been given to a formerly enslaved man from the South named Freeman who went on to become a major landowner in the area. But the photos raised questions. Who were these people posed in their finest clothes? What were their lives like? And why did no one know their story, when the legacies of historic white landowners were so often well recorded?

The questions lingered for years. Then, in 2021, the organization decided it was time to ramp up the investigation into the past, in a direct response to the nationwide conversation about confronting racism sparked by the killing of George Floyd.

“We felt a responsibility to learn more about who the family is,” Wellspring executive director Melissa Dimond says. “The forces in our culture that create the need for Wellspring are intimately connected to racism and injustice.”

Already busy with the work of providing emergency shelter for women and families, and providing job training to help struggling people achieve financial security, the staff added historical research to its list of duties. Digging into public records and local archives with the help of Gloucester’s Sawyer Free Library, the Cape Ann Museum, and a handful of community volunteers, these part-time investigators eventually discovered enough information that they were able to secure a grant from the Mass Humanities’ Expand Massachusetts Stories program to pay an academic researcher to assist in the search.

The story they have uncovered has answered some questions, overturned assumptions passed down through the years, and raised yet more avenues for exploration.

They identified the formerly enslaved man the stories referred to, but discovered the stories had it wrong. The man, Robin Freeman, was not enslaved in the South, but in Gloucester, by a man named Captain Byles. Byles did not release Freeman of his own accord; Freeman bought his own freedom, according to Byles’s account books unearthed during Wellspring’s research.

“There were people being treated as property, and it was here in Gloucester, whether or not we want to admit it,” Dimond says.

The house was not given to Freeman, but purchased by his son Robert, already a successful buyer and seller of property, in 1826. Robert Freeman was, it seems, the largest landowner in West Gloucester at one time, doing business with families with names like Bray and Stanwood, which have roads named after them in present-day Gloucester, unlike the Freemans.

In the face of this disparity, Dimond has contacted the city to ask about the process of getting a street named after a historical figure. She learned that street-naming might be too difficult to achieve, but that it is not too tricky to name a square, so she has begun looking into the process of creating a Freeman Square near the Wellspring house.

The research found that a Freeman descendant was the first Black member of the Salem police force. It also tracked down some living descendants of the Freeman family. The organization reached out to those it found and has started conversations with seven of them, none of whom knew the stories Wellspring was uncovering. As the investigation continues to locate more branches of the Freeman family tree, Dimond hopes Wellspring can eventually help bring them together at the property their ancestors once owned.

“We want to create an opportunity for as many descendants as possible to meet,” Dimond says.

The research Wellspring has completed has been assembled into a permanent exhibit in the building. The exhibit is open to the public during regular events and can be viewed by private appointment. Dimond hopes the work they’ve done so far—and the continued research they intend to do—will inspire visitors to look into the stories of their own communities and homes.

“There’s this myth that Black history can’t be known, but there’s a lot we can learn,” Dimond says. “We want to be part of telling the truth about society and be part of the solution.”