To Michael Updike, slate shingles are a unique, premade canvas for his art. And if they’re marred with paint splotches or leftover tar, he’s hit the jackpot because “it makes it more interesting,” he says. To this North Shore sculptor and slate carver, the rough-hewn surfaces that have been “marinating” on rooftops in all kinds of weather look like paintings, with textures, degrees of shading, and subtle differences in tonal values, ready for repurposing according to his inventive imaginings.

Updike works out of his home at the edge of a salt marsh in Newbury. The garage next to his studio is stuffed with finished artworks as well as untouched slate pieces of all sizes. “I decide what kind of image I want to put on it,” he says, “and oftentimes it talks back to the tonal qualities I can see in the slate. I always think fish, and don’t know why. I look at them as a brain with a locomotion system attached to it.”

But he’s drawn to other subjects, too—forgotten, unglamorous animals like pigeons, crows, mice, or dragonflies.

To begin, he sketches his concept onto the surface with a white charcoal pencil. Then he puts on headphones, dials up NPR, and, with his slender chisel and mallet, chips purposefully into the brittle gray surface to get the cleanest, sharpest lines. It’s definitely not brute force; rather, it’s the repeated tap, tap, tapping against the grain that achieves the unmistakable delicacy. “My carving of it is cutting beneath the patina to the fresher stone,” he notes. Little by little the subject emerges, with dust filling the grooves. Dust, a plus in his opinion, builds up and lends desirable contrast. “It will stay there forever, as long as there’s not a nor’easter,” he says with a grin.

As if by willful alchemy, the new artwork layered on top of the natural art transcends the slate’s original purpose, resulting in a fresh, new image never seen before.

Updike studied at Massachusetts College of Art, where he majored in sculpture. Later, he earned an MFA from the Vermont College of Fine Arts. In 1992, he began designing tabletop giftware and decorative art for Mariposa, a gift and tableware company in Manchester; he has created thousands of designs for them over the years. He approaches this work from a “sculptural point of view,” he says. He sculpts the prototype, and then releases it to manufacturing partners to be cast in alternative alloy metals. No two pieces are exactly alike. The products come back as tabletop and giftware items. “The pieces look like silver and polish like silver that could be put on a table,” he adds. Recently, the company has added ceramics back into their offerings, and Updike designs in the this medium as well.

After the death of his father, writer John Updike, in 2009, Michael experienced a tectonic shift in his artistic awareness. He set out to commemorate his father’s life in a meaningful and also aesthetically unique way. But first he had to learn the intricacies of gravestone art. Already he had experience carving in granite and marble, but slate required another skill set. He explains, “You have to carve in a totally different way.”

Scouring yard sales, he found discarded pieces of slate, on which he practiced “to get a feel” for the different stone. He learned three-dimensional v-cut lettering from a carver in Rhode Island, which creates crisp little valleys and allows you to read inscriptions as light passes over the stone, “just as the Romans did,” he says.

Natural pigments embedded in the slate break the constancy of the gray coloration. Updike never adds paint. However, he does make a few allowances and will use gold or silver leafing to accent pieces. “In my art I do make death heads and winged skulls as a nod and recognition to the early folk artists of New England,” he says. “I can tell a carver’s style and feel. We won the American Revolution but looked back toward the neoclassical influence in creating gravestones, instead of the pagan skulls and wings with so much personality. Now you have urns and weeping willows, which are stagnant.”

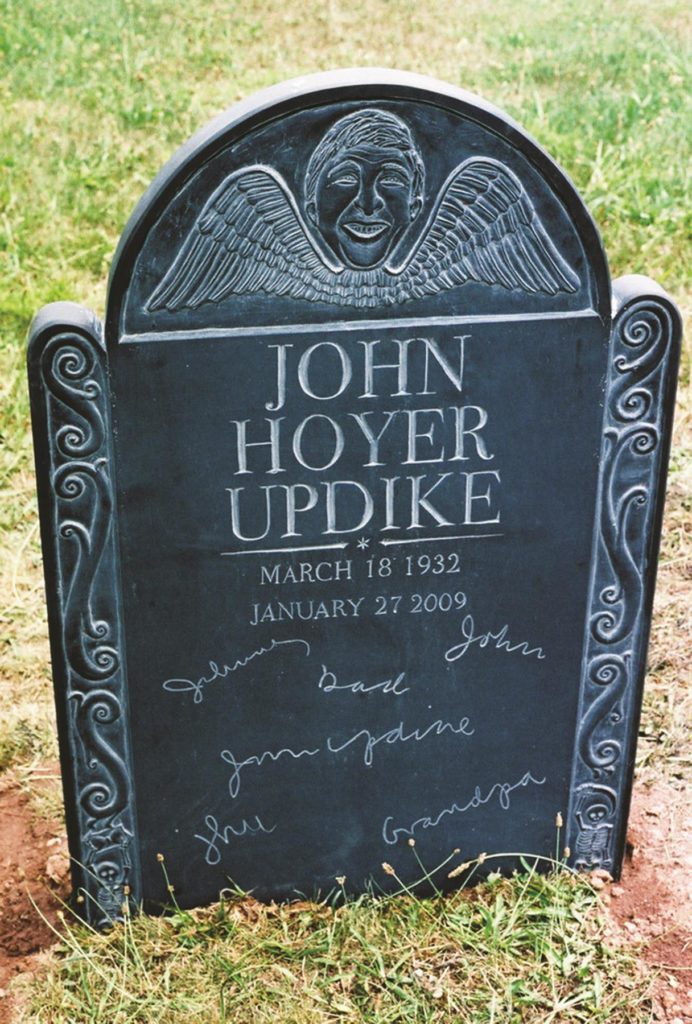

When he was confident enough of his skill, he carved his first intricate gravestone for his father, to be erected as a memorial in Plowville, Pennsylvania, where the elder Updike lived as a teenager. His ashes are interred both there and in a cremation garden behind a church in Manchester. “He feared death so much that I had him smiling, and I gave him a death head—or winged skull—so he’s happily ascending to heaven.” Beneath the date lines are various ways he wrote his signature.

On the back of the gravestone, Updike carved an early poem written by his father. It’s positioned beneath “a giant crow coughing up telephone poles at the bottom as it goes along.” He adds, “As I understand it, the poem got rejected by The New Yorker. But when he put together his first volume of poetry, it was included.”

Soon a commission followed, after the death of his father’s friend; subsequently, he realized he had found a new métier in memorial art. “It’s very exciting for me,” Updike says. “It takes me to a wide-range gamut of emotion, because I can suddenly be working with a parent who lost a child, or I can be working with very ironic people who want to do their gravestone before they die. A lot of jokes and humor could be built into it. You have to be ready for each one.

“The journey of getting the stone is what helps them recover and heal,” he continues. “Not completely, but to a certain level where they can move on. There’s a little bit of being a psychoanalyst, a little bit of being a pastor or minister, or just sometimes being a friend realizing their vision.”

Custom gravestones range in price between $4,000 and $15,000 per stone.

Over the last five years Updike has carved more than one gravestone for himself, “with the idea of rendering it obsolete, of course,” he says, his blue eyes twinkling. “The first one I did not put on a date. I put a bunch of numbers falling off a cliff. You’re supposed to choose the most optimistic one. But I thought it artistically cowardice not to put the death date on your gravestone. And I’m happily here to carve yet another one.”

contact michaelupdike.net