For people on the North Shore, Armenian last names are familiar. They’re the names of friends, neighbors, and colleagues. But despite that familiarity, few of us know the history of how and why the Armenian people made the journey to the United States and eventually called Massachusetts home.

“I’ve been living here for 50 years…it’s amazing how I didn’t even know who my neighbors were,” says Tom Vartabedian, a long-time Haverhill journalist of Armenian descent who’s the co-author, along with Haverhill High School social studies teacher E. Philip Brown, of the new book, Armenians of the Merrimack Valley.

“We’re very anxious to get the Armenian story out to people who don’t really know it,” Vartabedian says. “And even if they do know it, they’re going to be surprised to find out about their neighbors.”

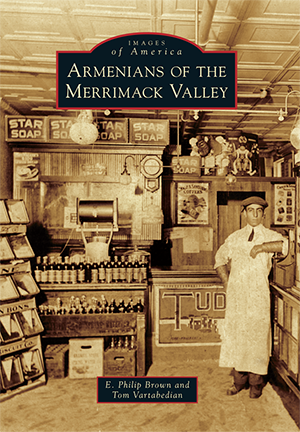

The book is published by Arcadia Publishing, which has published many, many other local history titles with the now-familiar looking sepia-toned cover photos, including New Hampshire Covered Bridges, Gloucester and Rockport, Andover in the Civil War, and Lawrence in the Gilded Age, that zero in on snapshots of people and places. The new book, Armenians of the Merrimack Valley, published in early February, is a “pictorial and editorial overview of the Armenian life in Merrimack Valley since the genocide 100 years ago,” Vartabedian says, referencing the 1915 Armenian genocide by the Ottoman Empire that claimed between 800,000 and 1.5 million victims and drove so many others out of their homeland.

Many of those who fled Armenia during that terrible period after WWI landed in the Merrimack Valley, which boasted a booming industry and secure life for workers in mill towns along the Merrimack River.

“There was gainful employment here….We had the shoe industry in Haverhill,” Vartabedian says. “These people went to work, and whatever they earned went toward raising their families and bringing other immigrants over.”

Throughout 128 pages and 179 photographs, the book covers the early 20th Century period through today, discussing everything from immigration, athletics, military life, business life, education, culture, church life, and more.

Brown was moved to be part of the book after Vartabedian gave a presentation to one of his history classes about genocide, noting that although he knows many people who were affected by the Armenian Genocide, he knew very little about it.

“People I’ve known my whole life never really described what they went through with their families,” Brown says. “I teach world history. I teach about WWI. This is really only a couple of paragraphs in textbooks.”

He and Vartabedian say that in addition to teaching and sharing with readers the story of Armenians in the Merrimack Valley, they also hope their book shines a light on the Armenian genocide and genocides in general. The two often do talks at high schools and colleges about human rights and genocide education.

“The Armenian genocide is often referred to as the forgotten genocide,” Vartabedian says, noting that a handful of countries—Turkey and the United States among them—haven’t formally recognized the events as a genocide.

“We won’t let the world forget,” he says. “It’s books like this that remind people that if you ignore history, it has a tendency to repeat itself.”