“I wouldn’t deceive you for the world.”

This was the catchphrase of Howard Thurston, the most famous magician of the early 20th century. While his flamboyant, theatrical brand of magic is overshadowed in cultural memory by the dramatic stunts of Harry Houdini, it was Thurston’s ability to make rabbits turn into boxes of candy and women levitate that made him the quintessential “magician.”

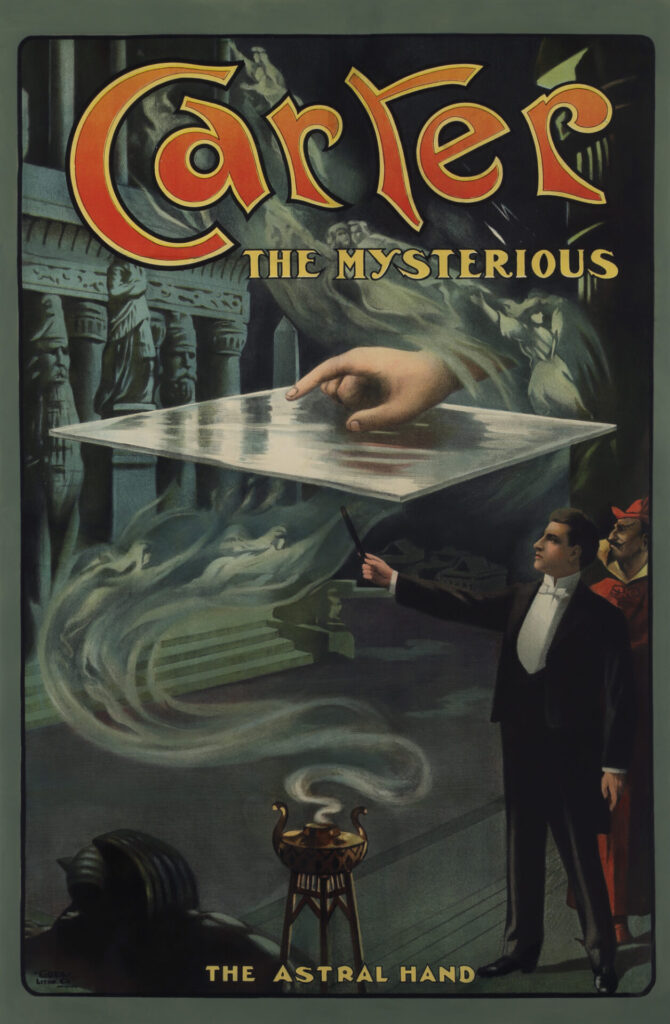

That’s why a six-foot poster to one of his shows, from 1929, opens a new exhibit at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem this season: Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic, and Mediums. The exhibit centers around artwork and objects of mediums and magicians, primarily from the Spiritualism movement of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The exhibit takes viewers back in time to the height of the American Spiritualist movement—a time “when people actively debated whether you could connect with the spirits or not,” says George Schwartz, curator-at-large for the PEM and the exhibit’s lead curator. It brings folks back to a time of parlor seances, Ouija boards, dazzling stage performances, rabbits coming out of top hats, and a thin veil between the natural and the supernatural.

The Spiritualism movement was centered around a main premise: “that spirits exist in the natural world, and that you can communicate with them through a medium,” explains Schwartz. “This became a topic of popular interest, no matter whether you believed it or not.” Of course, magicians and mediums still exist today. But back then, Schwartz says, the topic was all the rage.

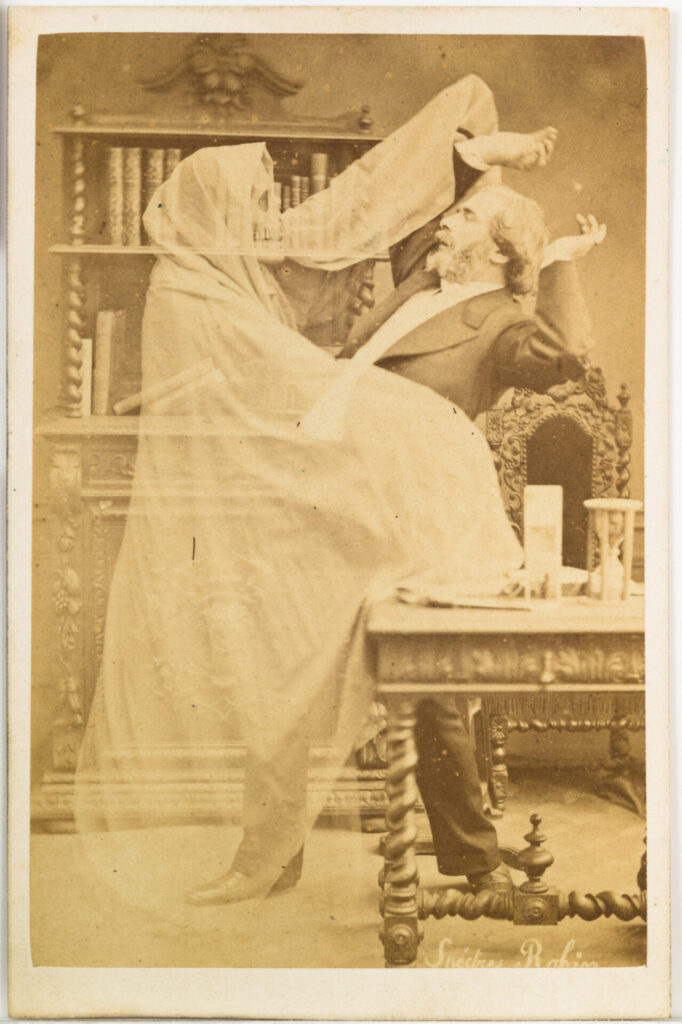

The exhibit displays around 185 objects, from paintings, posters, and films to apparatuses that magicians would use on stage. You’ll find spirit trumpets said to amplify the voices of the dead, mourning jewelry from the 18th century, and early spirit photography, which still has modern practices.

The show culminates in one of the most iconic pieces of magic paraphernalia: a Ouija board. And it brings these artifacts from the “golden age” of magicians and seances into the present day, too, with objects like an ESP guitar with a Ouija board pattern on it, recently played by Metallica’s Kirk Hammett. “The show is very experiential,” explains Schwartz, full of vignettes and interactive displays so visitors can immerse themselves in a sense of magic.

wood, and plastic. Collection of John Gaughan, Los Angeles.

Photo by Jeff Chang.

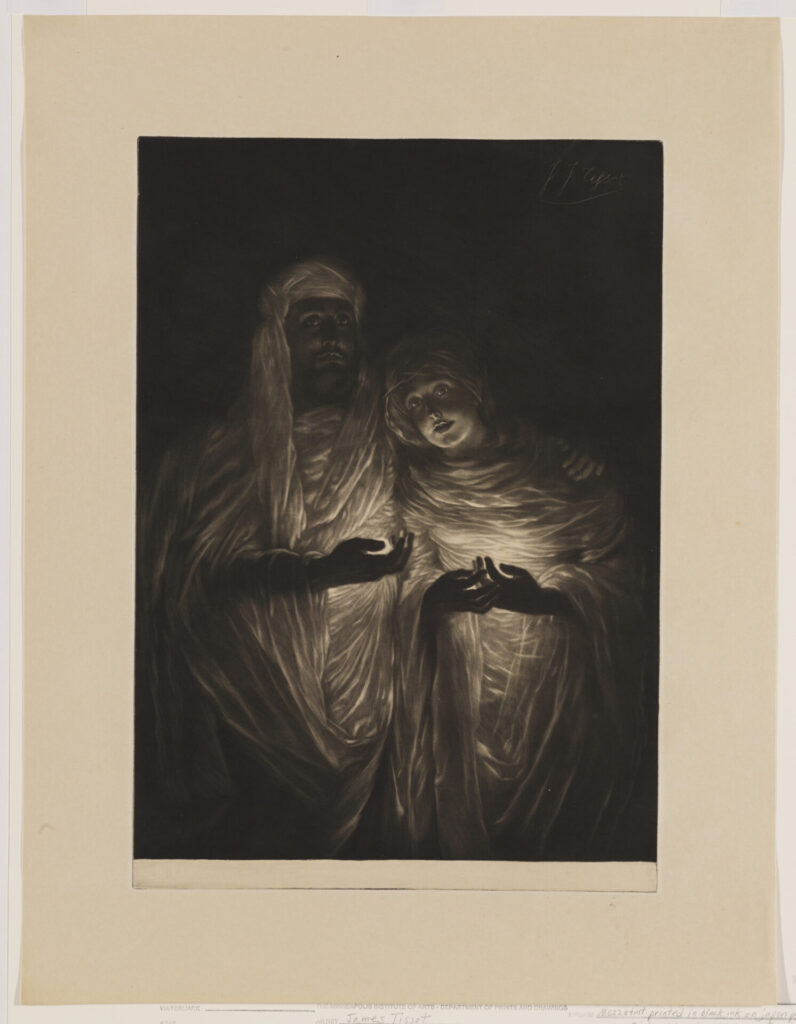

(The Mediumistic Apparition), 1885.

Carborundum mezzotint. Minneapolis Institute of Art,

The Richard Lewis Hillstrom Fun

Art Museum, Washington, DC, gift of International Business, Machines Corporation

And the exhibit goes beyond just a collection of cool objects—it dives into the history of Spiritualism and the neuroscience behind magic, too. “Spiritualism as a movement has had two great peaks in interests, explains Schwartz, “connected to the American Civil War and the First World War.” When people lost loved ones abroad, with no way to mourn traditionally in the home, they turned to this idea that we can communicate with the dead.

The Peabody Essex Museum’s on-staff neuroscientist provided context throughout the exhibit, also giving “a sense of what the brain’s role is in forming beliefs,” says Schwartz, and explaining “how people who might share the same lived experience might interpret it in different ways.” Seeing isn’t always believing.

That’s evident in the tension between magicians and mediums, too, explains Schwartz. “[They] had almost this symbiotic relationship—they kind of borrowed from each other, railed against each other as frauds and nonbelievers,” says Schwartz. “There were magicians who performed exposés on stage, showing how mediums were doing their tricks,” says Schwartz. “So that’s where this rivalry comes about.” Mediums were acting with supernatural agency—magicians weren’t.

Collection of Tony Oursler. Photo courtesy of Oursler Studio.

(1873-1883), 1884. Oil on canvas. Private Collection. Image

Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum.

That’s where the neuroscience comes in—the science of belief. “A magician might expose the tricks of a medium, but the true believers in Spiritualism will say, ‘That’s just how the magician’s doing it.’ So you’re shown something but that doesn’t necessarily change your opinion,” says Schwartz, drawing a parallel to our modern world that’s “filled with illusions in the digital form.”

Conjuring the Spirit World’s timing with Halloween in Salem is no accident, of course. And while the exhibit functions as a gateway to the museum for the thousands of out-of-towners who flood Salem throughout October, it runs through February 2—so locals can stop by and visit without battling the Halloween crowds.

On select Saturdays from 12 noon to 3 p.m., throughout the run of the show, two local magicians (Anton Andresen, the Official Magician of Salem, and Evan Northrup, a Boston-based magician and theater artist) will perform a show in the exhibit’s gallery itself, inspired by the illusions and magic tricks featured in the exhibit.

Schwartz hopes visitors will come to Conjuring the Spirit World for the fun paraphernalia and stay for “this larger message about perception and identity and how that influenced belief systems,” he says. Sure, the supernatural is cool—but communication with the supernatural is often about “connection, comfort, and closure,” he says.

Magic isn’t really all that complicated, anyway. It’s about the desire to be astounded.