Here on the North Shore, we love to go to the beach. We’re proud of the maritime history of our seaside towns like Gloucester and Salem. We love our seafood, our ocean breezes, our boating trips, and our nautical décor.

Dan Finamore at the Peabody Essex Museum shares this affinity for the sea—he’s spent his career in marine art, currently serving as PEM’s associate director for exhibitions and the Russell W. Knight curator of Maritime Art and History. This summer, he’s curated a new PEM exhibit on American marine art called In American Waters, in collaboration with Austen Bailly of the Crystal Bridges Museum in Arkansas.

“For much of my career dealing with marine art, I always thought that the net regarding what constitutes marine art should be cast more widely,” says Finamore, explaining the “arbitrary boundaries” around what has historically been considered marine art.

Above, Michele Felice Cornè (1752-1845), “Ship America on the Grand Banks,” about 1800, oil on canvas, 39 3/4 x 56 inches (100.965 x 142.24 cm), gift of Mrs. Francis B. Crowninshield, 1953, M8257. © 2014 Peabody Essex Museum Photography by Kathy Tarantola

This summer, PEM casts a wider net than ever before. The show features over 90 works from 38 lenders, and they aren’t all simply 19th-century paintings of tall ships. The show’s oldest work is a 1680 piece from Thomas Smith, while the most recent is a 2020 seascape by Cherokee Nation painter Kay WalkingStick.

While we now have other modes of transportation, trading, and communication besides the sea, oceans continue to hold immense relevance in our 21st-century lives—if we only knew where to look. Over 90 percent of the world’s commerce travels via ocean. The sea influences weather patterns the world over. And the ancestors of many of today’s Americans arrived in this country via boat.

“I’ve seen all sorts of art that was influenced by exposure and experience of the sea or the impact of the sea in American culture,” says Finamore, who was especially meticulous about choosing 20th- and 21st-century art for this exhibit. “[Maritime themes] are a huge force in our lives today. They’re top of mind in so many conversations,” says Finamore. “Regarding commerce, and today it’s about the environment, it’s about migration, it’s about climate change.”

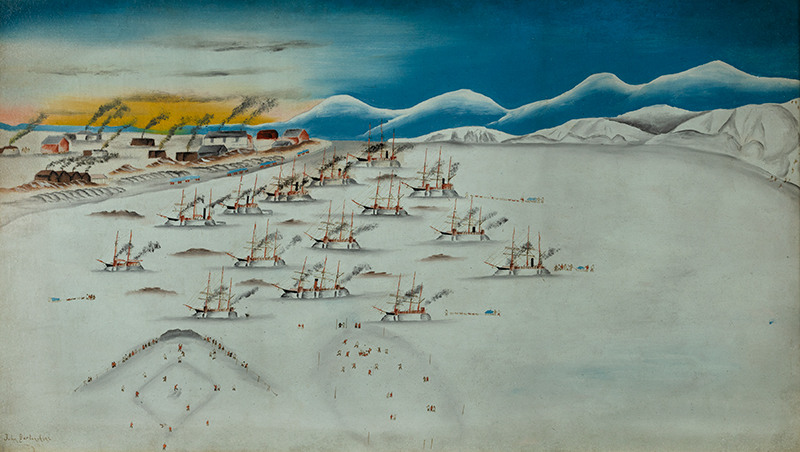

John Bertonccini (1872 – 1947), “Whaling vessels in the Ice,” Herschel Island, about 1894-95, oil on canvas, 18 x 31 in. (45.72 x 78.74 cm), museum purchase with funds donated by the Maritime Art and History Visiting Committee, 2019, 2019.33.1. Photography by Kathy Tarantola

“To look anew at American marine painting, we studied and analyzed its colonial and Eurocentric origins,” says Bailly. Maritime painting has historically evoked imagery of merchant ships on the high seas and realism portraits of old vessels. But sometimes maritime painting is about American ambition, like in John Wesley Jarvis’s massive portrait of “Commodore Perry at the Battle of Lake Erie,” or American joy, like in “Precious Jewels by the Sea” by Amy Sherald, official portraitist of First Lady Michelle Obama, which depicts Black children playing at the beach on a sunny day.

Sometimes, maritime imagery represents American pain and tragedy. “Huge numbers of Americans have looked to the sea as a negative aspect of their own heritage. They got to America because their ancestors were enslaved,” says Finamore. “So their associations with the sea are not for freedom and the future.” Sourcing paintings representing that aspect of maritime history was a challenge for Finamore, as few historical paintings represent those horrors of American chattel slavery.

Charles Sheeler, ‘Pertaining to Yachts and Yachting,” 1922, oil on canvas, 20 x 24 1/16 inches (50.8 x 61.1 cm), Philadelphia Museum of Art: Bequest of Margaretta S. Hinchman, 1955, 1955-96-9, courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Photograph courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum

The significance of maritime art bleeds into modern pop culture, too. The exhibit features Howard Pyle’s “Marooned,” depicting a pirate marooned on an island. Pyle, explains Finamore, through his pirate paintings, helped create the narrative of the swashbuckling Atlantic pirate. While the reality of piracy at the time was “hideous,” says Finamore, Pyle’s art inspired countless movies, books, and caricatures of piracy that persist today.

Certain works in the exhibit invite viewers to slow down and look inward—“Some of these paintings are very contemplative and the sea represents the vastness of nature, our role within that, our small place,” says Finamore, describing William Charles Richards’s seascapes that depict a vast and “relentless monotony of waves.”

Conrad Wise Chapman, “Submarine Torpedo Boat H. L. Hunley,” Dec. 6 1863, about 1864, oil on board, 00985.14.37a, courtesy of The American Civil War Museum, Richmond, Virginia. Photograph courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum

Finamore says he wants museum visitors to come away from this exhibit with a deeper understanding of “the centrality of the sea in our lives,” and how the sea has impacted and continues to impact American culture today. “They eliminated things in the 19th century and they eliminated things in the 20th century,” says Finamore of the narrow boundaries historically drawn around marine art.

The sea holds countless stories, emotions, and meanings, asserts this exhibit. It holds history and consequences, and it holds the future.

“We are all so globally integrated by sea,” says Finamore, “and it’s built into the way we think about our own connections to the world.”

Give a little thought to that the next time you dip your toes in.

For more information, visit pem.org/exhibitions/in-american-waters.