“I petition to your Honours, not for my own life, for I know I must die . . . but. . . that no more Innocent Blood be shed . . . .” wrote Mary Esty from her prison cell in Salem as she faced death by hanging in 1692.

Those who claim Salem witch fatigue may wonder if there is anything new to say about the Salem Witch Trials. But how about going back to make sure we know what was said in the first place? Selections from the world’s largest collection of authentic Salem Witch Trial materials and documents will be on view this fall at the Peabody Essex Museum. The collection, housed at the Phillips Library, hasn’t been on display since 1992 on the 300th anniversary of the trials.

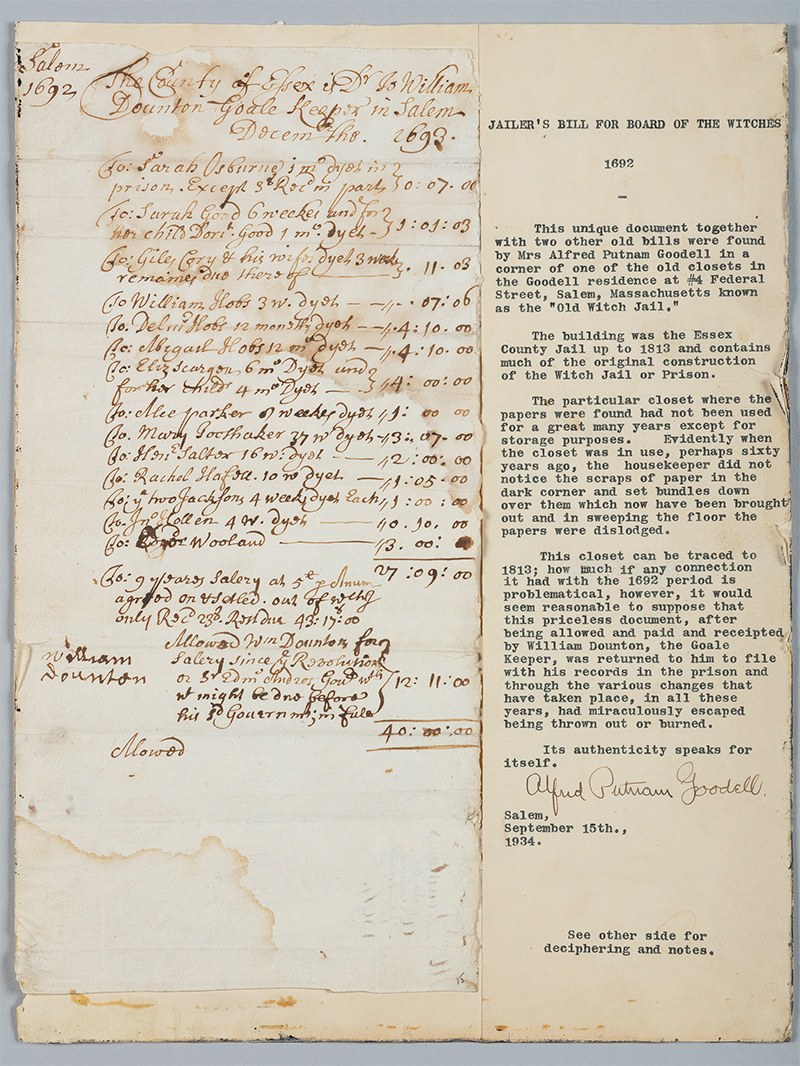

The yellowed death warrant for the execution of Bridget Bishop, the first of 19 people to be eventually hanged, petitions and invoices from the jail keeper tell the story of the hysteria. All led to the deaths of 25 innocent people—men, women, and children—between May 1692 and March 1693. They are paired with objects from PEM’s collection, the personal possessions relating to those involved, such as a trunk that belonged to Judge Jonathan Corwin, who resided at the 17th-century Salem building known today as the Witch House. There are also two original beams from the Salem Jail and an 1855 painting from PEM’s collection, Trial of George Jacobs by Tompkins Harrison Matteson, that details the pandemonium in the courtroom as the drama unfolds, including the man’s own granddaughter pointing an accusing finger.

The exhibition includes a memorial wall dedicated to the victims, where visitors will be asked to reflect on the loss, as well as the ignorance, intolerance, and fear that led to the tragedy. With so much noise in Salem every year at this time, this is a wonderful opportunity to present the actual facts, says PEM’s head librarian Dan Lipcan. “It’s incredibly exciting to see them in person,” Lipcan says. “To realize that real people were writing these documents and dealing with this crisis and this miscarriage of justice.”

To get the facts straight, PEM employed local experts to consult on the exhibition, including Emerson Baker, professor emeritus and assistant provost at Salem State University, whose expertise is 17th-century New England. He has written extensively on the witch trials, publishing a 2015 book called A Storm of Witchcraft: The Salem Trials and the American Experience.

Not dissimilar to the many layers enveloping 2020, the early settlers of Salem had endured a smallpox scare leading to the hysteria, as well as changes in weather that made growing food difficult. Baker also traces the hysteria to weak government in 1692 when the people of Massachusetts Bay were awaiting a new charter and a new governor from England. By the time the new governor arrived, the jail was already full of the accused.

“You can go anywhere in the world and you mention that you’re from Salem and people will say, “Oh, the Witch City, right?” says Baker. “A Salem witch hunt, to this day, is synonymous with rushing to judgment, to fanaticism, to extremism. And it’s a term used by everybody, of every political side: left, right, and center.”

But Baker says a lingering shame remained in the Salem community, with a desire to leave the tragedy in the past. In 2016, Baker led the dedication of a memorial at the exact spot in Gallows Hill, now a residential neighborhood, where the hangings took place. He thinks it helped the community and the world receive some healing from the tragic events.

“I had all these people filling my voicemail, calling to thank me,” he says, “to thank Salem, to thank the Gallows Hill team for making sure this story is not forgotten.”

As Salem works to further embrace the legacy, the Salem Witch Museum is giving out packets of information on each of the victims to their visiting descendants. The museum staff spent time during the pandemic shutdown to research more sites in Essex County related to the Witch Trials. The legacy has helped shape the Salem community into one of more inclusivity, says Tina Jordan, executive director of the Salem Witch Museum. “There’s more awareness in Salem. I believe that the community has really grown into accepting, understanding, and welcoming people who are different,” she says. “I think some of that comes with the sensitivity of so many different people practicing different religious beliefs. It’s a beautiful community.”

Roberta O’Connor, a board member on Voices Against Injustice, the organization responsible for the Witch Trials Memorial on Charter Street in Salem, agrees that the lessons have offered the community a gift: one that will be further explored this fall when visitors to Salem can see the actual documents at PEM.

“For me, the important thing is that these folks come away with a deeper understanding of the circumstances of the trials, because once you understand the history and what was happening in this area at the time, the lessons become much clearer,” says O’Connor. “The exhibit will be instrumental in teaching folks. And then for them to come out asking ‘What were the lessons? What should we look out for?’”

The Salem Witch Trials 1692 opened at PEM on September 26, and runs through April 4, 2021. Join Dinah Cardin and her co-host Chip Van Dyke this fall for a two-part episode on the Salem Witch Trials from PEM’s podcast series The PEMcast, featuring interviews with curators, experts, and community members. Find it on pem.org or wherever you listen to podcasts.

For more information, visit pem.org.