Tomorrow, January 18, the Peabody Essex Museum debuts a series of paintings by famed American painter Jacob Lawrence—a series that hasn’t been reunited since 1958. Lawrence, one of the best-known black artists of the twentieth century, painted Struggle: From the History of the American People between 1954 and 1956, during the civil rights era, and aimed to depict a broad narrative of U.S. history, showcasing the underrecognized and unsung alongside the founding fathers.

For Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle, PEM, over the past six years, rounded up twenty-five of the original thirty paintings. An additional three unlocated works were reproduced, while two of the paintings remain unlocated and unrecorded, still “displayed” by empty frames. Accompanying installments are also on display by artists Bethany Collins, Derrick Adams, and Hank Willis Thomas.

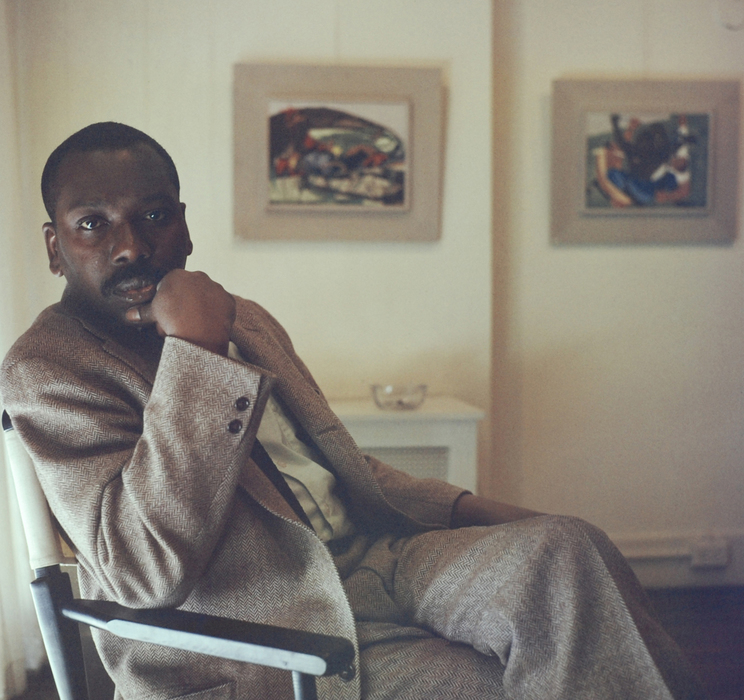

Lawrence broke into the art world at twenty-three when he debuted Migration Series in 1941, which became the first work by a black artist acquired by the MoMA. Known for his series of modestly scaled panels illustrating sweeping historical epics, Lawrence created narratives mostly focusing on black American resistance and perseverance.

After spending five years researching his Struggle project at the 135th Street Branch of the New York Public Library, Lawrence set out in 1954 to shed light on the “struggles, contributions, and ingenuity of the American people,” he wrote.

Painting this project amid the fraught political climate of the 1950s, during movements like desegregation and McCarthyism, Lawrence sought to answer questions like, “Who is an American?” explained PEM’s executive director Brian Kennedy, and “Who gets to tell America’s story?”

Lawrence accompanied each painting with quotes from primary sources like speeches and letters that he came across in his studies, quoting historical voices rarely heard along with lines from such documents as the Declaration of Independence. “…For freedom we want and will have,” reads a caption from a Georgia slave, “for we have served this cruel land long enuff.”

The almost-abstract works are fairly small, only twelve by sixteen inches each, requiring the viewer to have an intimate experience with each work to even observe what it’s depicting. The longer you look at a painting, the more details emerge. A bright azure blue ties all the paintings together, making them visually cohesive, while red, usually in the form of blood, draws the viewer’s eyes across each panel.

“There’s a lot of noise in this exhibit, I find,” said Kennedy. Of course, the exhibit has physical noise—from Collins’ America: A Hymnal, playing an a cappella recording of 100 different versions of “My Country ‘Tis of Thee,” to Adams’ video Saints March (2017). But between the bright colors, sharp angles, and emotional subject matter, the exhibit is loud. “The series shows a complete rendition of the human experience,” said organizing curator Austen Barron Bailly. “It goes deep into what makes us human.”

“We need Lawrence now more than ever,” said coordinating curator Lydia Gordon, adding that we need him to help us envision a way forward through our current polarized political landscape. “His art has the power to encourage these difficult conversations we need to be having.”

The PEM offers free museum admission this Martin Luther King Jr. Weekend, January 18 through January 20, to honor the opening of the Lawrence exhibit. A full roster of programming, including live music, artmaking, storytelling, and more, can be found on their website.

The exhibit, by organizing curators Elizabeth Hutton Turner and Austen Barron Bailly and coordinating curator Lydia Gordon, is on view January 18 through April 26, when it will move to the Metropolitan Museum of Art for the second leg of its five-stop national tour, also including the Birmingham Museum of Art, the Seattle Art Museum, and D.C.’s Phillips Collection.