The first time I attended Racket Shreve’s annual art show, it was probably over a decade ago. I was new to Salem and felt lucky to be brought along, glimpsing something authentically New England that most visitors to Salem would never see.

On a warm, festive evening last fall, Salemites turned up at the Chestnut Street home Shreve shares with his wife, Martha, to see his latest work. Shreve, now 72, busied himself at his framing station while a sea of humanity crammed into his attic studio and leaned in to see the perfect details of the lifelong artist’s latest work. Some of us wondered aloud if there were more night scenes this year, ships seemingly awash in a squid ink sky. This prompted a conversation about the artist’s nocturnes—and how the term “nocturne” came to mean more than just a form of music championed by Chopin.

“I sold every moonlit scene I did, even the unframed,” says Shreve, a few days after the opening. “They’re very tricky to do. You have to put down some substantial washes, and if you don’t get ’em right, there’s no turning back.”

His giant sea serpents, wrapped around boats and navigation markers, also fly out the door, he says. How many, I ask.

“Ugh, a lot.”

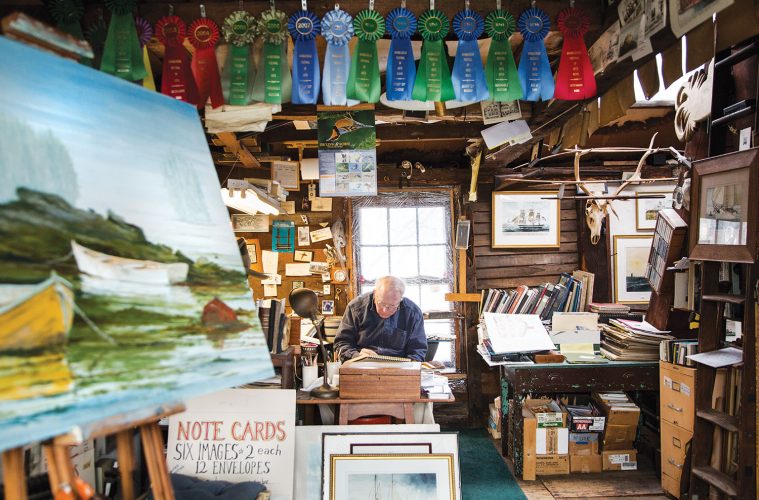

Shreve makes about 150 watercolors a year, maybe five oils, and countless pen-and-ink drawings. I watch as he goes back through the show’s guest book, looking for patterns, returning fans, and newcomers. He remembers a friend I brought along and points out her name. These books line the rafters of Shreve’s studio, as does just about every piece of memorabilia from his entire life. Soon it becomes clear that this will be an illustrated conversation. With a commitment to posterity, or at least to storytelling, it’s almost as if Shreve is curating someone else’s space…or life story. Every topic has an artifact that “explains everything,” he says. Reference books, objects, documents—it’s all here, taking you through decades of a life and Salem’s history.

Want to know what he was up to in, say, 1987? Pull down that particular sketchbook, among hundreds, and have a look for yourself. Want to know about the “Massachusetts Duck Stamp” by the artist? There is evidence. This place, where he spends all day, every day, starting at 8 a.m., is warmed by a wood stove, an amiable dog, and the sunlight that filters through old skylights. A hatch in the floor closes with a 30-pound counterweight. And there you are, sealed in this attic world, surrounded by the life of Racket Shreve in what was a family barn. “This is a business,” he says, looking around. “I have to sell paintings to survive.”

A 1968 graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design, Shreve was also a field illustrator in the Army and produced propaganda pamphlets during the Vietnam War. Later, he took a two-year journey around the world, sending home his sketchbooks. As a freelance illustrator in Boston, his work appeared in Boston Magazine and the Atlantic Monthly and in Salem books on local history. Today, Shreve seems like one of the last of the lot, a surviving true maritime painter on the North Shore. His work is part of the permanent collection at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM). And he’s been exhibited for more than 50 years around New England. His works hang in many of the finest historic homes in Salem. Whether maritime art is your thing or not, Shreve is to be admired . His paintings render ships at sea in perfect, storm-tousled detail.

“Racket’s maintaining a regional tradition of a local marine painter, who will both interpret the coastline for the general viewer and paint a picture of your boat on commission. Such artists date back for 200 years in Salem,” says Dan Finamore, PEM’s Russell W. Knight, curator of maritime art and history.

Without the pressure to paint for the annual show, he’d have to paint the back stairs, Shreve jokes, and then talks of doing serious marine art when he spent days painting his sailboat before he sold it. This was back when he sailed out of Juniper Cove “about a gazillion times.” A part of the maritime community, Shreve has intimate knowledge of the area’s inlets and coves. When Abbott Rock, a stone monument in Salem Harbor since the age of sail and a feature in many of Shreve’s paintings, blew over in a 2010 storm, he was part of a group of sailors who “put it back.”

On rainy days as a child, the Salem native would draw (with permission) on the walls in the kitchen or go to PEM to look at paintings. His mother worked there, so, naturally, a giant dragon mask from some type of celebration hangs from the studio ceiling. As does a vintage bottle of bourbon that tells the story of his Southern ancestors who built riverboats on the Mississippi and helped develop Shreveport, Louisiana.

Born Warren Shreve, he was given the nickname Racket for being a loud child. He is the descendant of the Shreves who followed the gold rush out West, eventually becoming the Boston jewelry empire Shreve, Crump & Low. The Shreve I ran across on Federal Street as I sought permission to write this profile was much quieter, standing on the sidewalk, camera in hand, shooting a home that once belonged to one of his ancestors. He had been commissioned to paint it, and the leafy tree in front proved vexing, behaving in an uncooperative way for the shot.

“Shreve creates a detailed image of a vessel with all the signature elements clearly delineated—a figurehead, distinctive hull shape or paint job—and sets it within a recognizable background so you can see the boat is in Salem Harbor, off Misery Island, or rounding Eastern Point,” says Finamore. “Then there is Racket’s humorous side, which focuses in on quirky aspects of maritime culture. He likes to have rats scurrying around his scenes, and has created amusing faux labels with maritime scenes for rum bottles.”

Black crows, seabirds, and other Audubon paintings have sprung forth in recent years. He’s had a murder of crows living near his Salem home his whole life, says Shreve. So why not paint them? “They’re kind of mischievous and fun,” he says, no doubt much like himself. Reacting to his environment is like breathing for Shreve. Magic abounds. Take the pit of fortune behind his house, where Shreve discovered a priceless trash heap of whole Canton plates, porcelain bits, and glassware that became the subject of a scholarly dissertation, as well as part of the collection at PEM.

“This place looked like a shard factory for about a decade,” he says.

At Shreve’s annual show, I often run into the same people, and we marvel at the artist’s sheer prolific nature. If being in his studio every year weren’t gift enough, we also get his body of work—a constant reminder of the water and history that surround us.

Racket Shreve Fine Art Studio

17 1/2 Chestnut Street

Salem, MA

978-744-4324