The Essex Base Ball Club honors the historical aspect of America’s favorite pastime. By Jeanne O’Brien Coffey // photographs by Matthew Muise

On a cold day in late February, with the third snowstorm in as many weeks brewing outside, a group of men at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm in Newbury was dreaming of summertime—cornfields, a cheering crowd, and maybe a cold beer in the warm sun.

Unlike millions of fans across the country, they were not planning for Major League Baseball’s opening day or the first swings of their company softball team. As the flakes fell outside, they were planning the 2013 season for the Essex Base Ball Club, a league that plays ball—and spells its name—by 1861 rules, for the fun of playing the game as much as the joy of bringing history to life.

Since the club’s founding in 2002 as a single team managed by the Danvers Historical Society, the group’s main goal has been to share the history of the American pastime while exposing more people to the unique style of play of the 19th century. For president and captain Brian “Cappy” Sheehy, it’s a dream come true. As a high school history teacher in North Andover, he knows firsthand how powerful history can be when people are engaged in it. And as a lifelong player of baseball, it combines two passions in a way he hadn’t expected.

“It’s kind of consumed my life,” Sheehy says. A tireless researcher, he has uncovered information about teams that played on the North Shore in the 19th century, along with team photos, logos, and other tokens from the early days. Since taking over management of the club in 2003, he has grown it from a single team with about 12 guys, who would travel to wherever they could find other history enthusiasts to play, to a group of more than 50 that plays in front of about 3,000 spectators each season.

The league is divided into five teams: The Lynn Live Oaks, The Newburyport Clamdiggers, the Lowell Baseball Nine, the Essex Base Ball Club, and the newest team, the Portsmouth Rockinghams. All names come from teams that played in the 19th century—but that can be a bit confusing. Although each bears the name of an area town, all the teams play at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm in Newbury with players from all over—new team members are assigned to wherever they are needed.

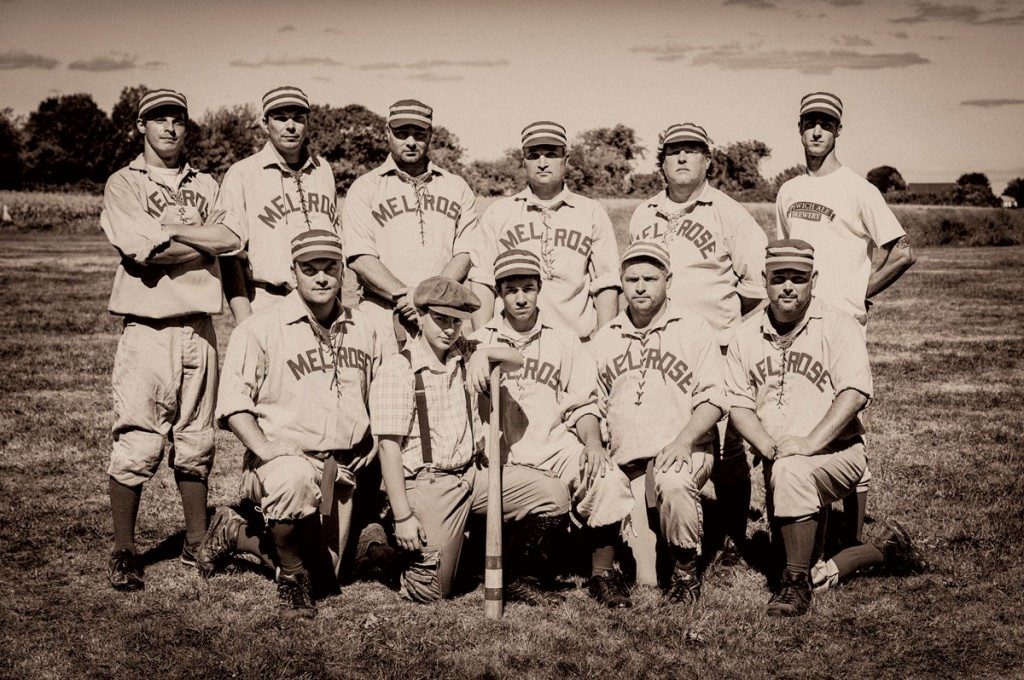

The Melrose Pondfielders

After hosting a few games sporadically over the years, Spencer-Peirce-Little became the league’s official home field in 2010. Before that, the teams traveled all over, mostly in New England, playing local historical societies and other groups. In many instances, they spurred such a love of the game that those towns went on to form their own leagues.

Interest in historical baseball isn’t unique to New England, however. The Essex Base Ball Club, made up of star players from the other four teams, travels to play in other parts of the country several times a year. Last year, the team traveled to Maryland to play the Elkton Eclipse, and afterwards, in a show of good sportsmanship, the Maryland players treated the Essex team to a meal of local crab. This year, Maryland is planning to travel north, and thanks to Woodman’s of Essex, the Essex players plan to return the favor. In honor of Woodman’s impending 100th anniversary next year, the restaurant has offered to host the 40 players for a lobster dinner, says Bethany Groff, regional site manager for Historic New England and manager of Spencer-Peirce-Little. The only thing the players need to do is wear their vintage uniforms for a photo shoot.

Groff couldn’t be more pleased with the relationship with Essex Base Ball. “We are so happy they are here,” Groff says. “They really add to the experience at the farm.”

Historic New England provides the field for the team to play on, manages the logistics of ticket sales, parking, and popcorn, and pitches in to advertise the events. It’s a terrific partnership, she says. “I spend my life trying to connect people to history. This is kind of like sneaking in the zucchini, so to speak—when people are watching a game, they’re not necessarily aware that they are also learning about history,” says Groff.

Sheehy’s group generally brings a display to every game, outlining the history of the game and the differences in the rules. Jeff Peart, who serves as umpire for the games, also acts as an unofficial Master of Ceremonies, helping the crowd understand the rules of the game and helping put the play in context. Peart certainly looks the part of MC, with a generous beard, top hat, and black frock coat. There’s a reason for his formal attire—back in the 1860s, the umpire was usually one of the most respected men in town, often a mayor or other city official or local lawyer. “Players wanted someone that everyone would respect,” says Peart, who has been with the team since the beginning, at first as a player. After he was injured during play, his wife asked him to step back from playing and instead take on umpiring duties full time.

As with many players, Peart was attracted by his love of history. “I love the historic period of the Civil War, but I’m not into guns,” he says, adding that the Civil War was a big reason for baseball becoming America’s pastime; the sport was very popular in New England and New York before the war. When the war started, soldiers traveled all around the country, teaching the game to other soldiers and even Southern prisoners of war. By the 1870s, baseball had exploded across the country.

As with many vintage baseball teams around the country, Essex Base Ball Club chose to follow the 1861 rules, because that was when baseball began to resemble the game as it is played today. There is a diamond with 90 feet between the bases, and players run around the bases to score. However, there are a few critical differences: The pitcher pitches the ball underhand, and players don’t wear gloves, because they hadn’t been invented yet at the time. If a fielder catches the ball on the first bounce, it is still considered an out.

That rule can be a tricky one for power hitters used to slamming the ball for a homerun, Sheehy says. “Nine out of 10 times, when you kill the ball, an outfielder can get it on the first bounce,” he says, adding that it means batters need to think more strategically about where and how to hit the ball. The most successful players tend to hit hard grounders.

Another major difference in play is that there are generally no balls and strikes, though if an umpire thinks a batter is wasting too much time at the plate, he can call a strike. This may change, however, as the team is considering a move to 1864 rules, when balls and strikes were called more often. “This can allow the game to flow more smoothly,” says Peart. “By 1861 rules, if a pitcher [is] wildly off the plate, there [is] nothing to be done; we just have to wait until he throws a good pitch.”

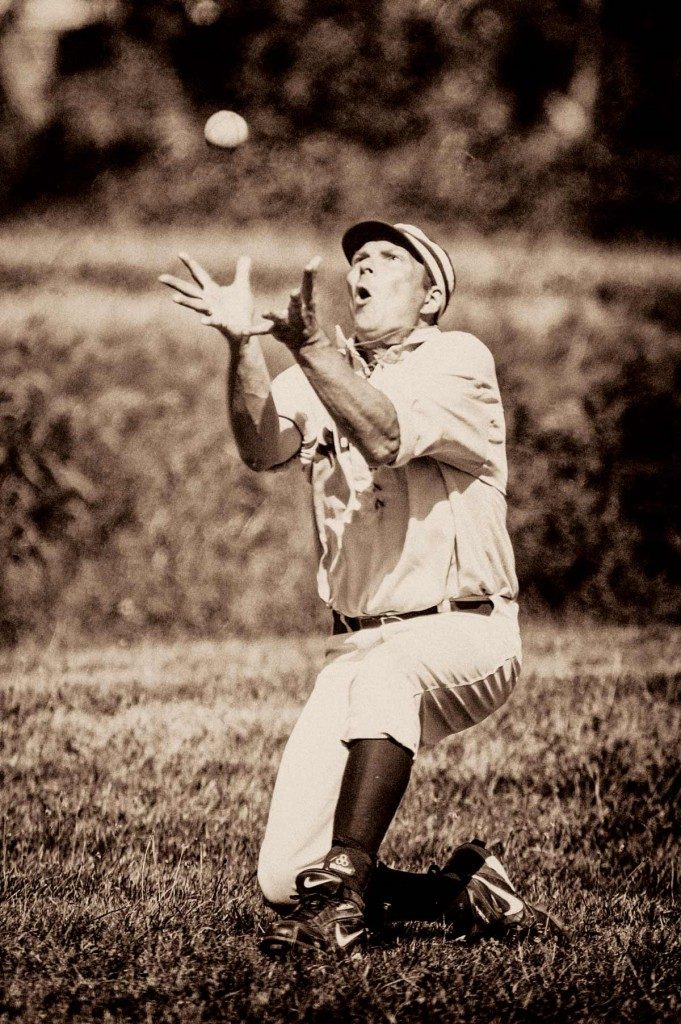

Ture to the past, outfielders play sans gloves.

Ture to the past, outfielders play sans gloves.

In keeping the experience authentic, players adhere to some strict guidelines. They are required to purchase vintage uniforms, which, fortunately, are made with some modern fabrics for comfort. No one can wear sunglasses, and forget about plastic water bottles; they must bring vintage-style growlers or canteens to drink from. Players even cover up the logos on their cleats.

But for all the attention to history, the games aren’t lacking in genuine competition. “Historical reenactments are stuck in roles,” notes Peart. “No matter how many times you fight the battle of Gettysburg, Lee is always going to lose. These games are exciting—crowds are cheering and especially when there is a close score, it is just as exciting as any other ball game.”

While teams are competitive, they are careful not to get out of hand. Sheehy notes that they strive for a gentlemanly atmosphere—swearing and fighting are strictly frowned upon. The hope is that the games eventually become a tourist attraction, and already, families are finding it a lovely way to spend a Sunday afternoon. If the kids get tired of watching the game, they can check out the farm’s animals, which include a massive pig and friendly goats, as well as chickens and a donkey. Sometimes, those animals even make a guest appearance on the field. “Every once in a while, we let goats and chickens onto the field,” Groff says with a laugh. “It adds to the authenticity [of the time].”

Corn fields that slowly grow to maturity over the course of the summer in the outfield also add to the authenticity. “There are no fences,” Sheehy says. “In the fall, when the corn is high, it’s kind of like Field of Dreams.” A ball lost in the corn must be found, as traditionally, players only had one ball per game. It’s a scenario that can lead to a home run, a whole lot of outfielders rustling around between corn stalks, and even some comedy. One outfielder hunted around for the ball, couldn’t find it, and instead emerged with a small pumpkin.

In addition to the fun, not to mention attracting people to Spencer-Peirce-Little who might not normally visit a historic site, Groff notes that the players often become ambassadors for Historic New England, as well as unofficial teachers themselves. It’s a responsbilitiy that team members take very seriously.

“We’ve spent a lot of time building up our reputation,” Sheehy says, pointing to 10 years of lectures on the history of baseball and travels to historical societies, schools, and camps—even those abroad. He urges players to familiarize themselves with the farm and the historic era, as well as the game itself. And it seems that players are glad to do it. “It really warms my heart,” Peart says. “After a game, the players would have every reason in the world to sit in the shade with a beer, but instead they are back out on the field, teaching kids about the game.”

Opening day for the Essex Base Ball Club is Sunday, May 5, at noon at Spencer-Peirce-Little Farm, 5 Littles Lane, Newbury. For the whole summer schedule and more information on the Essex Base Ball Association, visit http://essexbaseball.wordpress.com. ?n