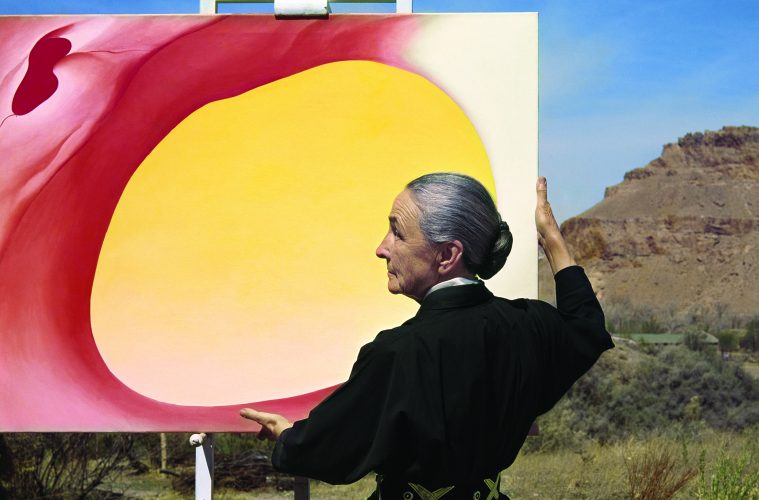

Like the most astute Instagram user, Georgia O’Keeffe knew the power of a single image. Just as people project themselves onto the world today, carefully creating their public face through social media, for more than 70 years the modernist artist crafted her public persona through her personal style, her domestic aesthetic, and the way she lived her life.

When Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style opens at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) on December 16, art lovers will move beyond her instantly recognizable paintings of giant sensual desert flowers to learn about this iconic artist’s personal preferences. Examining her lifestyle and the material culture she left behind as artifacts tells us a great deal more. It will be as if we had stepped inside her home, invited to peruse the intimate corners of her closet. In fact, that’s exactly what guest curator Wanda M. Corn did. A retired professor from Stanford University, the esteemed American art scholar spent more than 20 years creating this exhibition, which premiered at the Brooklyn Museum last spring.

.jpg)

When O’Keeffe died in 1986, Corn began to study the contents of the closets at O’Keeffe’s two New Mexico homes. The androgynous dresser saw her clothed body as another canvas on which to proclaim her aesthetic. Known for her look of “consistent and disciplined minimalism,” O’Keeffe donned Gaucho hats and Japanese kimonos, pieces worn by Chinese farmers and workers, severe black suits, and her well-worn swirly pin, handmade by sculptor Alexander Calder, that read “O’K.”

“For a younger generation, this is an old master that they are beginning to see for the first time,” says Corn, who now lives on Cape Cod. O’Keeffe’s life was as much an art form as what went on in the studio, says Corn. Through studying these different aspects of the artist’s life, blurring the line between art historian and biographer, what comes into focus is an interesting human being, says Corn, not just as an artist “but as a person who gave shape to her own life.”

Corn interviewed O’Keeffe in her home in 1980. Asked what she would like to discuss with her now, Corn says, “I would tell her how much I admired her consistency of vision and aesthetic and that I wonder how she maintained that clarity. She always looks gorgeous and put together in her way, which is not looking like a movie star, but is looking like Georgia O’Keeffe in a very tidy way.”

The exhibition includes nearly 200 works, not only in the expected forms of oil paintings and watercolors, but also clothes, accessories and jewelry, and 73 photographs of O’Keeffe and her homes, by the likes of Ansel Adams, Bruce Weber, Andy Warhol, and her husband, Alfred Stieglitz.

Vintage white blouses and dresses that kick off the exhibition are presumed to be sewn by the skilled seamstress O’Keeffe, displaying a fine stitch at a time when the artist could not have afforded a dressmaker. “I would ask if that is why she kept the early clothes because she had worked so hard on them,” says Corn. “That explains why she kept things that were probably 60 years old.”

People can expect to travel with O’Keeffe through her busy artist life in New York to New Mexico, where her style changed. Corn praises PEM’s team approach to mounting and designing exhibitions. “For me, it’s been fun to see how this material is filtered through the minds of staff who are working on it at PEM because that’s not necessarily how it’s been filtered at other museums and by other designers,” she says. “They hammer out what a show will look like and what stories it will tell. I’ve enjoyed the creativity of the process.”

-716x1024.jpg)

As is their way, the PEM, team has worked to make strong connections, showing the relationship between forms and motifs that O’Keeffe discovered in nature, teased out on the canvas, and replicated in deep pleats and stitches in her clothing. Her beloved V-shape neckline shows up again in her abstract compositions. “We’re putting a fine point on it to get people to stop and really appreciate the beauty,” says Austen Barron Bailly, PEM’s George Putnam Curator of American Art and coordinating curator for the exhibition. Collaboration with the museum’s neuroscientist has resulted in tactile stations where audiences can feel hand sewn silk and wool, noting small feminine details hidden within sleek lines.

Jeans and bandanas mingle with designer fashion, elevating ordinary, relatable clothing that the artist wore and made part of her style. “You walk into the gallery and you think, ‘oh, she’s this tall,’” says Paula Richter, PEM’s curator for exhibitions and research. The project has taught her more than she expected, says Richter, beyond desert still lifes. Richter’s personal interests are, fittingly, fashion and American decorative arts. She says, “It’s more of an intimate experience. It’s clothing she actually made for herself. It approaches her in a very holistic way that I find very meaningful.”

-809x1024.jpg)

The PEM team has been tracking the ways in which the Brooklyn Museum exhibition—which closed last July—has influenced 2018 fashion collections. And they’re poised to observe similar trends from PEM’s exhibition, charting the ongoing influence of a woman gone more than 30 years.

The curatorial department’s work has also led to studying how O’Keeffe became so famous late in life, like Iris Apfel, another fashion icon enjoyed by frequenters of PEM. “O’Keefee’s famous. She’s an icon,” says Bailly. “But how do you get there?” Digging into the Vogue archive at Harvard, the team studied the steady rise and fall of O’Keeffe’s fame. Glossy magazine profiles and documentaries are now moments in the exhibition, detailing her rise to celebrity. A spread in an interior design magazine shows us that by the time O’Keeffe reached New Mexico, her domestic style was gaining as much attention as her paintings.

.jpg)

Though PEM has shown several contemporary female artists in solo exhibitions in the last few years, featuring an American female modernist of O’Keeffe’s status and influence is something altogether different. “As a curator, building an American art program, one that’s focused a little more on painters, there’s still a desire to look at major American artists from new perspectives,” says Bailly. “We wouldn’t do an O’Keeffe show just to do an O’Keeffe show. We’re going to do an O’Keeffe show because it’s a completely different way of looking at her art and her life. First and foremost is how we’re going to see the paintings anew. How can we better know her, as a person, as an individual who led this very distinctive life in order to create those paintings?”

With Stieglitz, O’Keeffe embarked on a multiyear serial portrait project that ultimately led to her becoming the most photographed American artist of the 20th century and contributed to our understanding of the power of photography to shape public image. Younger viewers, says Corn, those who are dedicated to a practice of posting selfies, may see a version of themselves in O’Keeffe. “She has certainly given me information about a way to live a life that maybe, if I were 20 years old, I would pay attention to.”

Georgia O’Keeffe:

Art, Image, Style is on view at PEM, December 16, 2017, through April 1, 2018. pem.org