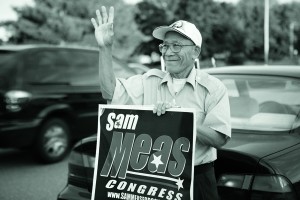

Haverhill resident, businessman, and one-time refugee Sam Meas retraces his perilous path to American politics. By Bryan McGonigle

In the mid-1980s, an immigrant boy was sent by INS to be examined by an orthodontist to determine his age. His Cambodian birth records were destroyed by the Khmer Rouge, the Communist supporters whose movement and power grab killed millions in Cambodia. The orthodontist guessed that the boy was born between 1970 and 1972; the boy settled on the latter as his birth year.

He then was given a calendar and told to pick out a birthday, a concept that was strange to him because there were no birthday celebrations under the Khmer Rouge. He chose December 31, not knowing it was New Year’s Eve or in the middle of a major holiday season.

“Had I known about Christmas and everything, I would have chosen a different day,” Sam Meas says, laughing, at a coffee shop in Haverhill. “Think about all the presents you lose out on.”

Today, Sam Meas still doesn’t know his exact age. But as a successful businessman, husband, father, and the first Cambodian to run for U.S. Congress, he does know that he’s a long way from the killing fields.

Sam meas, born sombo, also knows about loss. His journey began in the Kandal Province of Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge invaded his village and took his father away for “re-education.” Meas assumes his father was executed. Young Sombo was sent to a refugee camp along the Thai-Cambodian border with his mother and her sisters, but when Vietnamese Communists invaded that camp, Meas was separated from them. His cousin grabbed him and together they escaped, along with other refugees, to Thailand’s Kao I Dang, yet another refugee camp.

Sam meas, born sombo, also knows about loss. His journey began in the Kandal Province of Cambodia, where the Khmer Rouge invaded his village and took his father away for “re-education.” Meas assumes his father was executed. Young Sombo was sent to a refugee camp along the Thai-Cambodian border with his mother and her sisters, but when Vietnamese Communists invaded that camp, Meas was separated from them. His cousin grabbed him and together they escaped, along with other refugees, to Thailand’s Kao I Dang, yet another refugee camp.

“The journey in itself was very difficult, very treacherous,” Meas says. “If we were to be caught by the Thai soldiers, border guards, the police, or even the villagers, we would have been killed or robbed, and the women would have been raped. It’s a difficult journey-we had to walk through landmines. It’s the struggle that a lot of Cambodians experienced at the time. Even the journey from the village we were in to the Thai border was treacherous because there was fighting, a lot of killing. As a child, I witnessed a lot of atrocities, war casualties on the scale of unimaginable.”

After a few weeks of living in that camp, his cousin left and never returned. Meas stayed for three years. He performed various jobs in the camp-laundry, shoe shining, babysitting, chopping wood-to earn his keep. That camp was where Meas was first exposed to formal education. He attended primary school there and learned to read and write and received private English lessons from other refugees.

“I survived, but had I realized I could have gone to an orphanage, I would have gone,” Meas says. “But I didn’t know that, so what I did to survive was to sort of live off fellow Cambodian refugees in exchange for food and shelter and some affection. I performed all sorts of duties.”

The camp was surrounded by barbed wire and was guarded by Thai military to prevent people from leaving and to prevent others from entering. With his basic knowledge of Thai and English, Meas befriended a Thai colonel who brought him into his base. Meas would wash and iron his clothes, shine his shoes, and clean his toilets.

“When you’re a kid and you have that kind of access, to me it wasn’t as bad,” Meas says. “In retrospect, it was hell, basically, but at the time, it was better than what a lot of other people had in the camp.”

Meas adds that the rough life in the camp taught him several life lessons that would shape his future. He had to use a lot of common sense, and if he wanted help, he had to help himself rather than depend on others.

“I think that’s what has allowed me to prevail and to be as successful as I am, [and it’s what has] allowed me to survive-my ability to adapt to various conditions and adversity and also to help others in times of need,” Meas says.

But in 1986, meas got a shot at a new life. He was sponsored by Catholic Charities and given legal permission to come to the United States. Meas still remembers vividly his first trip to America as awe-inducing, flying over New York City and seeing its sea of bright lights. He describes it as “heaven.” When he got off the plane, he was overwhelmed by escalators, cars, highways, and other modern conveniences he hadn’t known in the camps. He was mesmerized by a vending machine, and the very idea that he could put a dollar into a slot and have a Coca-Cola come out. It was then at that airport that Meas began a lifelong love affair with carbonation.

Meas had often dreamed about coming to America as a child. He would flip through the pages of Time magazine and read what he could while admiring the pictures. He had a fascination with military hardware, particularly fighter jets. “I thought coming to America would allow me to become a fighter pilot,” Meas says with a laugh. “That dream hasn’t been realized yet, of course.”

Meas was sent to Virginia and lived there as a foster child with the Abbey family. In an amusing anecdote, he recalls the INS misspelling his name as “Sambo.” Meas didn’t correct them, because he was fine with whatever name he was given. But he also didn’t know that “sambo” was a pejorative term Southern white people called African-Americans decades ago. Starting a new life in Virginia with that racial slur for a name would likely cause a lot of unwanted trouble, so his name was changed to Sam. He liked the name Sam and kept it.

In addition to having English spoken around him at all times, Meas was able to further master the language through television-particularly soap operas. “I know all the stuff about ‘General Hospital,’ ‘Days of Our Lives,’ you name it. I know the whole thing,” Meas says. “One day, I mustered enough courage to ask my foster sister, ‘Rachel, how come there’s no ending to any of these stories? It goes on forever.’ And she just started laughing.”

In addition to having English spoken around him at all times, Meas was able to further master the language through television-particularly soap operas. “I know all the stuff about ‘General Hospital,’ ‘Days of Our Lives,’ you name it. I know the whole thing,” Meas says. “One day, I mustered enough courage to ask my foster sister, ‘Rachel, how come there’s no ending to any of these stories? It goes on forever.’ And she just started laughing.”

But Meas would find out that bright lights could be blinding. While adapting to the English language wasn’t difficult for him, adapting to American culture was. In retrospect, Meas says that although the Abbey family welcomed him with open arms, treated him very well, and provided him with everything he needed, he was still a foreign child struggling to cope with both the memories of treacherous refugee life and the cultural adjustment to American life. He eventually decided to leave the Abbeys to live in a group home just outside of Richmond.

Another year went by, and Meas then moved out of the group home and moved in with a woman named Susan Morey, a single mother and schoolteacher who would be his final foster mother. Legally, she couldn’t adopt him because of a U.S. law that prohibited adoption of children without a birth certificate. The home government would have to declare a child abandoned, and there was no government in Cambodia to do so.

“But aside from the legal aspect of it, Susan was a single mother and she is my mother, my [adoptive] mother, and we’re a family,” Meas says. His life stabilized with Morey. He skipped the eighth grade, attended an exclusive Virginia private high school on scholarship, and graduated from Virginia Tech in 1996 with a degree in finance.

After graduating from college, Meas decided to move north. The Abbeys were originally from Saugus, so while living with them, Meas visited New England several times and loved it. He got a job in Rhode Island as a sales rep for American Powers Conversion, but only lasted six months after deciding he wasn’t very good at sales.

Meas moved on to work at State Street Bank for about $25,000 a year-a lot of money then, especially for a guy who’d polished boots at a refugee camp for food. He stayed with State Street Bank for many years, during which he was sent to Alameda, California, for two years before going to New York City for one of the company’s highest-profile clients, General Motors Asset Management Co., GM’s investment arm. Although he wouldn’t make investment decisions there, he would get involved with researching data for portfolio managers at a time when GM had one of the biggest pension funds in the world.

“I’ve known Sam for a while, from State Street,” says Ray Murphy, current director of performance measurement at BlackRock in Boston. “He’s very hardworking, and I got along with him well. Later, when I was at BlackRock, I needed help.Sam was available, so he joined my team for a few years. He’s always very upbeat, ready to tackle any kind of project that comes along, and his personality is always something you remember about Sam.”

Drawing on the lesson he learned as a child about helping the less fortunate, Meas has volunteered for the North Suffolk Mental Health Association, based in Chelsea, as a member of its board of directors since 2001. The nonprofit organization provides community-based services to families dealing with mental illness, substance abuse, and developmental disabilities. He is currently the vice president of the board.

in addition to a successful career path, Meas found the love of his life, a nurse named Leah, in New England. She happened to stay at a party longer than expected, and he happened to show up despite being injured.

“It was by chance, purely by chance,” Meas recalls of their meeting. “I had surgery two days before. I went to a friend’s house for karaoke, and I was playing the sympathy card, and it worked very well. We had a very long conversation.”

The two had a lot in common. Leah’s first job was on an assembly line making $2.50 an hour, and Meas’s first job was pushing grocery carts for $3.50 an hour. They were both conservatives living in the blue Northeast. And both were Cambodian-born immigrants. But the coincidences of both their fortunate meeting and personal similarities paled in comparison to one thing they had in common: Leah’s family came to Boston from Cambodia in 1983 after fleeing from the Khmer Rouge and living in the Kao I Dang refugee camp. Two children survived the horrors of the Khmer Rouge and life in a refugee camp, and life’s countless twists and turns had brought them each to that party in Boston years later.

“I think it was destiny,” Leah Meas says. “I think where we met and how we met made it very special.” Leah had stayed at the barbecue longer than she’d planned, and when the children started screaming “Uncle Sam!” she noticed Sam arriving. Meas sat next to her then, and the rest was history. “It’s a day I’ll never forget: May 19, 1999. He was so handsome and smart!”

Leah gave Sam her number but didn’t expect anything to come of it, as he would soon be moving to California. In fact, she ignored his first emails, phone calls, and voicemails. But on his fifth attempt she gave in and they went on a date. They continued dating for the three weeks before he left for California. “During those three weeks, we were going out almost every night for dinner or dancing.”

For the next three years, the two dated long-distance. Sam would fly to Boston every six weeks and Leah would fly out west every six weeks. It became easier when Sam was transferred to New York in 2000. The phone bills, like the travel costs, were high, but they both felt it was worth it.

While Meas was in New York, the September 11 terrorist attacks happened and he had to re-examine his priorities.

“After September 11, of course, every American’s perspective of things changed. We had the option of living in New York City and me getting a job at General Motors in asset management or coming back here to live in Massachusetts,” Meas says. “Leah and I decided this was the best place to raise a family. We loved this area, and all of her family is here.”

The two were married in 2002 and moved to Haverhill to be closer to Leah’s relatives. They then started a family of their own. They now have two daughters, Monique and Sydney, now 5 and 3, respectively. Each was born on March 24, but exactly two years apart. Both were also born prematurely: Monique weighed less than two pounds at birth and spent three months in an incubator. Sydney was born weighing just 4.5 pounds. Both girls are healthy and active, but parenting two premature babies had its own challenges.

“Raising our premature daughters presented a major challenge for both of us as new parents,” Leah says. “It did put a lot of stress on both of us,” she says of juggling the demand of caring for a very tiny baby and full-time work. “Our greatest joy is that both of our girls are now healthy, smart, active, and playful. Watching them grow up to become little people is the greatest joy in the world.”

In 2008, meas’s political passions were ignited. Actually, he had been an interested observer of American politics since the 1992 Democratic presidential primary, when he watched a debate between Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton and former Senator Paul Tsongas. While in school, Meas met Tsongas, which sparked his interest in politics.

In 2008, meas’s political passions were ignited. Actually, he had been an interested observer of American politics since the 1992 Democratic presidential primary, when he watched a debate between Arkansas Governor Bill Clinton and former Senator Paul Tsongas. While in school, Meas met Tsongas, which sparked his interest in politics.

“So even though I have not been active in politics, I have been an outside observer of politics for quite some time,” Meas says. “And what I have been observing in Massachusetts is that this state is a one-party state that is dominated by the Democratic Party. To me, that’s bad for democracy in general. You need to have an opposing viewpoint.”

An enthusiastic Republican, he holds fond memories of Ronald Reagan, the man who was leader of the free world when he came to America. Meas had credited the Reagan Doctrine of fighting Communism for his being brought to this country. He also valued Reagan’s call for personal responsibility and freedom.

When Barack Obama was elected president, Meas was impressed by voters’ passion and was excited to have the first African-American president elected. But he was disappointed that on Congressional ballots there were no real challenges to the incumbents, especially in Massachusetts. Meas says it reminded him of elections under Communism, where people were allowed to vote, but only one party was presented as an option.

“So one thing led to another, and I said, ‘You know what? We are fighting two wars at the cost of a trillion dollars so the people in Afghanistan in Iraq have the right to choose their representatives,'” Meas says. “I decided I wanted to do something.” With a flare for the dramatic, Meas woke his wife up in the middle of the night and told her he was going to run for Congress.

“So one thing led to another, and I said, ‘You know what? We are fighting two wars at the cost of a trillion dollars so the people in Afghanistan in Iraq have the right to choose their representatives,'” Meas says. “I decided I wanted to do something.” With a flare for the dramatic, Meas woke his wife up in the middle of the night and told her he was going to run for Congress.

“I thought that he was out of his mind!” Leah said. “Initially, I thought he was joking, but he was persistent. Eventually, I agreed with him that the country is going in the wrong direction.”

Meas talked to residents in the district and eventually persuaded Leah to support the idea. He resigned from his job at State Street in April of this year to focus all his attention on his campaign.

Massachusetts elections tend to favor incumbents. In the congressional race, the primary is held in September, giving the challenger just a few weeks to campaign. At press time, the congressional primary had yet to take place. But regardless of the outcome, Meas says his run was intended largely to prove a point-that with the right support, a challenger can still defeat a well-funded incumbent-and to express his dissatistfaction with current politics.

“The professional politicians, Republican and Democrat, have destroyed our economy,” Meas says. “They’ve polarized everything. There’s sheer arrogance; they ignore us on every issue, they vote and tell us what they want, not what we want. Look at the mess that they have left for us.”

The BP oil spill, which Meas says has exposed vast incompetence in government and lack of leadership, as well as the immigration controversy and what Meas says is a lack of effort to secure American borders, have added more fire to Meas’s passion to win a Congressional seat.

“He’s very concerned about the issues, does a lot of research on things,” Murphy said. “And he’s very concerned about everyone he works with, so he’d make a great representative in Congress.”

Leah has a laundry list of things she’d like her husband to accomplish for the country and Massachusetts’s fifth district-including lowering taxes, cutting regulations, and bringing more businesses to the district. But just as importantly, she says, he should “remain true to himself, stay grounded, continue to be the man I married, and fight every day to preserve the America we have come to love. It’s a precious thing we have, being American. We need to protect it for ourselves and, more importantly, our children.”

To unseat a Democratic incumbent in Massachusetts, and the wife of the district’s legendary native son, would be a daunting task. At press time, Niki Tsongas’s campaign had reported large fundraising amounts, while Republicans, including Meas, lagged far behind in donations. But Meas’s passion and life story have captured the attention of the fifth district. Meas hired former U.S. Attorney Frank McNamara this summer as his campaign’s finance chairman to help him get an advantage in the state’s small but influential conservative community. That Lowell, the district’s largest city, is home to more than 20,000 Cambodians doesn’t hurt, either.

Meas has returned to Cambodia and Thailand multiple times. His wife has extended family there. But he and his family have gone there as Americans-tourists only- and have generally visited the beaches, ancient relics, and other popular spots he missed out on as a child running from bloodshed.

“It still is a very poor country,” Meas says of his homeland. “I didn’t see a lot of development. There’s some, but like with any third-world country, there are the extremely destitute, the extremely wealthy, and nothing in between.”

That contrast between the elite and the poor and his memories of the horrors of Cambodia’s past remind Meas of the gift he received when coming to America, and he says that’s what he has held on to in this campaign.

“I’m not afraid to stand up to the powers,” Meas says. “I survived the Khmer Rouge. I’m running for Congress because I want to serve my country, and I want to preserve that American dream. To be here in America, to live in this country, it’s a privilege every day.” ?n

*Sam Meas lost the primarys