After a red-hot run with the Syracuse Orange, Hamilton native Michael Carter-Williams prepares to test his mettle in the NBA.

Every day around the world, there are hundreds of thousands of kids playing basketball and dreaming of making it to the NBA one day. Growing up a scrawny, small-town kid in Hamilton, Michael Carter-Williams was one of them.

The reality is, in an average year, hundreds of people across America will become millionaires by winning the lottery. Hundreds of others will be struck by lightning. And only about 70 will join an NBA team. But a funny thing happened to Michael this summer: He made it to the NBA.

Of course, Mandy Carter-Zegarowski always knew her son was talented. Athletically, Michael starred as a Little League catcher and the quarterback of his Pop Warner football team. Off the field, he was outgoing, personable, and popular. “He always had a lot of friends,” Mandy says. “He had all this energy, and he was a very funny kid.”

But more than anything, Michael was a natural on the basketball court. Mandy and Earl Williams, Michael’s biological father, both played college basketball at Salem State, and Mandy won 150 games over 10 seasons as head coach at Ipswich High School. (Michael goes by Carter-Williams as a way of honoring both parents, although he refers to his biological parents and their respective spouses as his parents.)

Zach Zegarowski started dating Mandy when Michael was 18 months old; they married when he was four. Zach played college ball at UMass Lowell and spent 10 years as an assistant coach at powerhouse Charlestown High School. “We’re a basketball family,” Michael says. “From my parents to my sister and brothers, I’ve always been surrounded by the game.”

Along with spending time playing with Earl, Michael would often tag along with Zach to Charlestown practices. Over the years, the stepfather/stepson relationship blossomed not only into a father/son relationship, but also coach/player. By sixth grade, Zach could see that Michael was serious about the sport.The two would go through personal practice sessions, lasting about 90 minutes. In seventh grade, Zach started bringing Michael to practice against the Charlestown junior varsity team. A few years later, when Michael was a scrawny high school freshman, Zach had him playing in men’s summer league games.

And then there were the one-on-one games.

“We must have played 10,000 games of one-on-one, and I never let him beat me,” Zach says. “He had that competitive nature, and he would get really mad. Like, we wouldn’t talk in the car on the way home. He’d complain to his mom, and sometimes she’d take his side. And sometimes she’d just say, ‘You’ll just have to get better.’ “

When Michael was a freshman, the Zegarowskis assembled a local travel team that they called Mass Hoop Elite. Michael was their youngest player, but also their best. They were too good for the usual opponents in the suburbs, so they started scheduling tougher competition from Boston. And they kept winning.

Michael’s first breakthrough moment came in a close loss to Boston Amateur Basketball Club, the best AAU program in the area. He scored more than 30 points in the near-upset, catching the attention of BABC coaches. As the saying goes, if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em; a year later, Michael did just that.

“We started to think, maybe he could get a scholarship one day,” Mandy says. “Zach had a scholarship to UMass Lowell, and we saw the kind of good that it did, so that’s the goal we were hoping for.”

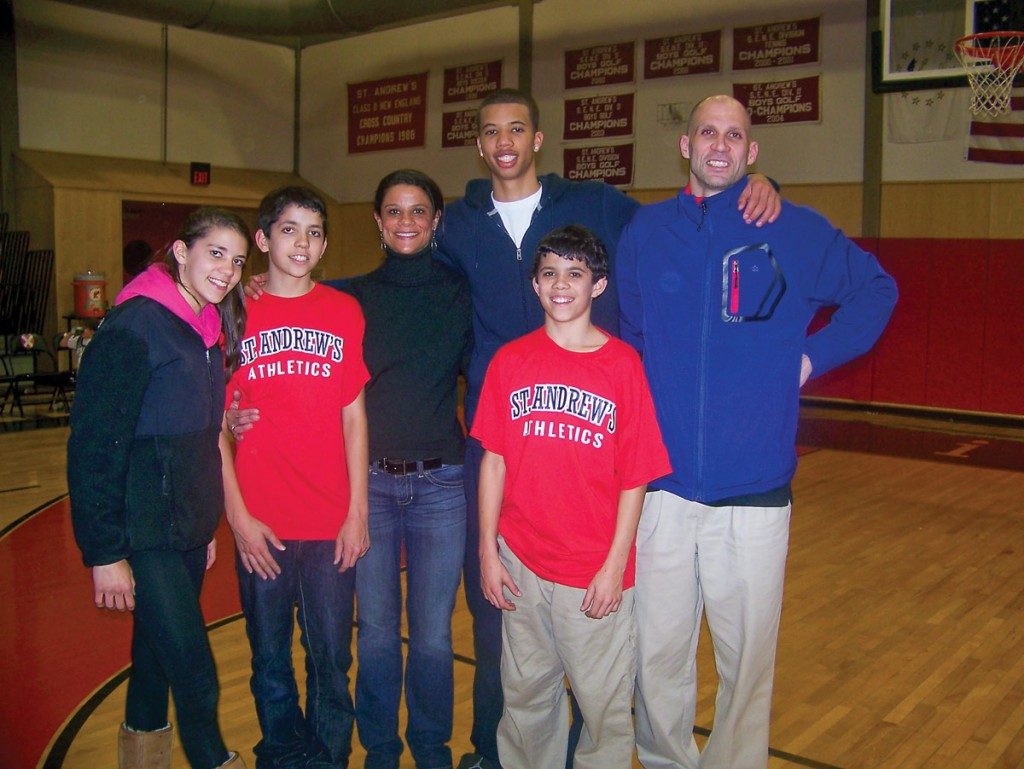

Carter-Williams with mom Mandy, stepdad Zach, and siblings.

Michael spent a year prepping at St. Mary’s High School in Lynn, repeating the eighth grade, before starting at Hamilton-Wenham Regional High School in 2007. As they were every year, basketball tryouts were split into freshman/sophomore and junior/senior sessions.

“When the first session was over, we asked him to stay around for the juniors and seniors,” says Marty Binette, the school’s long-time varsity coach. “He was the best player in both tryouts that day.” At five-foot-nine, he was just average height for a varsity guard, not to mention scrawny. But he still dominated, averaging 20 points per game for a team that went 14-4.

However, it would be his only season at Hamilton-Wenham. He got a scholarship offer from St. Andrew’s Academy in Barrington, RI, which meant a bigger basketball schedule against better competition, plus a chance for more exposure to college programs.The first scholarship offer came during his sophomore year from the University of Rhode Island, a Division I school in one of the nation’s stronger mid-major leagues. It was more than the family could have hoped for.

That same year, Syracuse University Associate Head Coach Mike Hopkins took notice. Michael was then about 6’ 0″ and 130 pounds. Syracuse was a member of the Big East conference, not only one of the nation’s elite leagues, but one known for a brutally physical style of play. The Zegarowskis’ first instinct toward Syracuse was along the lines of “Yeah, right.”

But Michael continued to play well at St. Andrew’s, and he was shining in premier national tournaments for BABC. He grew taller and stronger (6’ 5″ and 175 pounds by his senior year), and other top colleges were also taking notice. But in the end, it was Syracuse.

It was at Syracuse when his basketball career hit the first (and, so far, only) bump. Syracuse already had three established guards, so Michael sat the bench. A lot. In fact, for 11 of Syracuse’s 37 games, he didn’t get off the bench at all. “It was the first time in my life, in any sport, that I had to deal with not playing,” Michael says. “It was tough. I’m a competitor, and I wanted to play. But I got through it. It helped me become a better player in the end.”

Michael took on a “first one at practice, last one to leave” mentality. After the season, teammate Scoop Jardine’s eligibility was exhausted, and Dion Waiters left for the NBA. A starting spot was open. As a sophomore, Michael was asked to not only step in, but step up as the focal point of the team’s offense. He blossomed into the best player on one of the nation’s best teams; his 7.3 assists per game led the Big East.

Syracuse was playing well heading into March Madness. Opening the NCAA Tournament in San Jose, the Orange breezed past Montana to set up a Saturday night matchup with Cal Berkeley. Early on in that game, Michael spotted Mandy in the crowd, clearly shaken, though she was trying very hard not be a distraction during what would be a workmanlike victory.

After the game, Mandy told Michael the news: Their house had burned down. Mandy and Michael’s sister Masey, 16, were in San Jose for the game and were left with only what they packed. Zach and 14-year-old twins Maxwell and Marcus were home and escaped unharmed, but their house and belongings were lost. The cause of the fire remains unknown.

It was a helpless feeling for Michael and the whole family. But help was on the way. The communities of Hamilton, Ipswich, and surrounding towns rallied and pitched in to provide the family with the basics to get by in the short-term. They’ve since been renting a house in Ipswich.

“We’re so blessed,” says Mandy. “We had this tragedy—our sons watched our house burn down. But then to have the community come forward and be so supportive, and they still are, it’s just been amazing.” The family isn’t sure exactly where their next permanent home will be, but they’ll likely keep a home base in Hamilton. Masey will attend Brewster Academy next year, and the twins start at Hamilton-Wenham in the fall.

If the loss of his home was weighing on Michael, it didn’t show on the court. In his next game, he led Syracuse to an upset of top-seeded Indiana, scoring a collegiate career-high 24 points. Two days later they beat Marquette, and Syracuse was back in the Final Four for the first time since 2003, when the Orange took home the title.

The season didn’t have a storybook ending, though. Syracuse ran into a red-hot Michigan team in the national semifinals. With 74 seconds left and trailing by six, Michael fouled out. Fans didn’t know it yet, but it would be his last game for SU.

In a rare move for a soon-to-be multimillionaire, Michael stayed in Syracuse for the remainder of the spring semester to finish the core classes needed for his degree in communications (he’s a few classes—all available online—short of his degree). Zach relocated to Syracuse to work him out on a regular basis. Then, on April 10, Syracuse released a statement that Michael would enter the NBA Draft.

Fast forward to June 27. It’s an early summer night in Brooklyn, NY. David Stern, the NBA’s long-time commissioner, steps to the podium at the Barclays Center to announce that with the 11th pick of the 2013 NBA Draft, the Philadelphia 76ers select… Michael Carter-Williams.

“We always told him, ‘Never think that you’ve arrived,’ ” Zach says. “He still has a chip on his shoulder. That’s why I think he’s going to be a good pro.”

In the coming weeks, Michael will set up his new life in Philadelphia, and for the next decade or so, he’ll live out his dream. While he does, there will be other kids playing in school gymnasiums, city parks, and dusty driveway courts, some of them in small New England towns.

It’s a longshot, but maybe one of them is the next Michael Carter-Williams. ?n