Bicultural identities—that’s something many of the residents in Salem’s Point neighborhood have in common. The primarily Dominican population has roots in the Caribbean and familial ties in the States. That duality is depicted in paint on two large murals that have been recently resurrected after languishing out of sight for years.

As part of the 15 Ward Street Pocket Park & Public Art Project, which transformed a dump site into a small urban park, two murals—originally painted in 1997—were replicated by Oliver Brothers Fine Art Restoration and Conservation in 2015. At the project’s helm was the North Shore Community Development Coalition (CDC), a nonprofit agency that receives grant money from state and federal sources and funnels it down to the local level. “They are basically going in and improving neighborhoods,” says Oliver Brothers principal Greg Bishop. Such was the case for the lower-income Point neighborhood.

“They originally wanted to restore them,” says Bishop of the murals. “They contacted us because we are a restoration company, but I went to see them—they were in basements and covered in mold…. They were really too far gone.” Ultimately, they decided to re-create the murals using the same panel form, though instead of plywood like the originals, they opted for a much more durable medium-density fiberboard.

To start, they transported all of the rotting four feet by eight feet sheets of plywood to their shop in Beverly, where they photographed all of the panels for reference. “We quickly realized the most efficient thing to do was to trace the murals on the original panels using translucent tissue paper [versus doing a grid transfer from photographs],” explains Bishop. “Then we took the new panels and flipped them over and drew on the front so we had a reverse negative, which we transferred onto the new panels so we had a chalk outline.” The entire Oliver Brothers staff worked on the project from mid June through August, and Bishop hired a number of additional artists to work on detailing.

Looking back to 1997, CDC’s chief program officer Rosario Ubiera-Minaya explains how, over a period of several months and under the guidance of youth project coordinators, the Point’s young people designed and painted the murals. As a college student and neighborhood resident, Ubiera-Minaya served as one of those youth coordinators. She notes the participation of Salem Access Television as a way to bring video and technology into the fold—an important initiative in a community seeking advancement. (It also made for a multi-media project.) A United Way grant enabled CDC to hire John Ewing, an internationally known muralist. “He worked with kids from the neighborhood for a number of months exposing them to art and murals from around the world,” says Ubiera-Minaya. “He taught them how art can be used as a tool for sending a message.”

The two murals now on display are part of a series of three. The third was much smaller and portable—it was used as a public outreach tool to explain the project. The students involved in painting the original murals were all neighborhood residents and ranged in age from 5 to 19. “Discussions with them [revealed] they wanted to show their culture, where they were coming from, as well as how they felt about…being split between two worlds,” explains Ubiera-Minaya. The smaller mural on canvas depicts a tree rooted into both sides of a scene—on one side, Caribbean culture is represented with colorful scenes of family togetherness, on the other is a cityscape featuring ideas of education and employment; overhead, a plane crosses from the Caribbean to the United States. “Family is what keeps them together,” notes Ubiera-Minaya. “There’s family on the island and in the United States.”

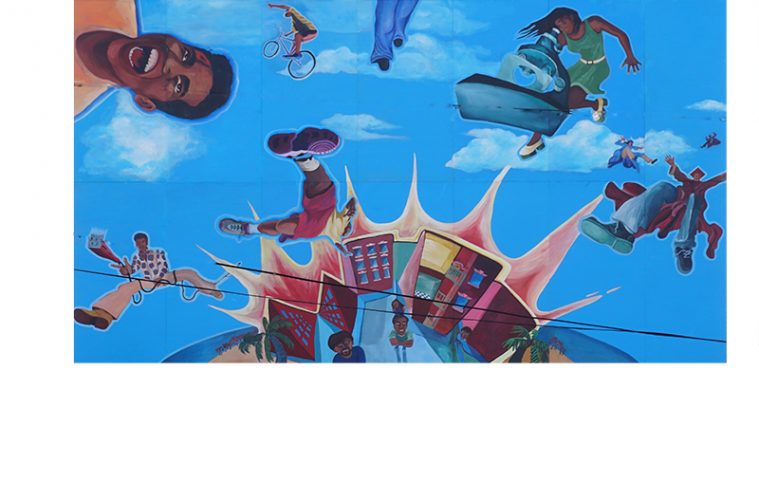

The Harbor Street mural tells the story of what it means to be part of the neighborhood. “It shows everyday life in the Point and highlights their activities as well as iconic residents from the neighborhood, and how they brought their culture into the neighborhood with celebrations and family life.” The third and largest mural is on Ward Street and represents the young people’s aspirations for the future. In it, they are seen reaching into the sky toward symbols of success.

“I share the students’ feelings,” says Ubiera-Minaya. “I am bicultural. I think those three murals truly represent how we feel about coming to a new culture and a new country…. Seeing those murals—I see myself reflected in them.”

The idea for all of CDC’s endeavors is to engage residents and to attract visitors. “We have big dreams for public art in the neighborhood,” says Ubiera-Minaya, noting that the mural project was the first opportunity for CDC to work on a large scale “using public art for advocacy and as an educational tool.” There are other such projects in the works. In fact, they recently completed the Crosswalk project on Salem’s Peabody and Dutch Streets. Ruben Ubiera, Rosario’s brother, who also grew up in the Point neighborhood, was the muralist for that project—he is now a world-renowned painter. And a shining example of the power of public art.

CONTACTS

Oliver Brothers Fine Art Restoration and Conservation

117 Elliot St.

Beverly

617-536-2323

oliverbrothersonline.com

North Shore Community Development Coalition

102 Lafayette St.

Salem

978-745-8071

northshorecdc.org