By noontime on a chilly Saturday afternoon in Gloucester, every seat at the well-worn bar at Halibut Point Restaurant & Pub is filled. A muted TV shows golf, but the regulars pay no mind, nursing their drinks and good-naturedly joking around.

It might seem like an odd place to bring my kids, five and seven years old, for lunch, but we all felt perfectly at home. The girls rummaged through a toy box in the corner, guided by our friendly waitress, while my husband and I enjoyed a plate of oysters and a cold Fisherman’s Ale from nearby Cape Ann Brewery.

Dennis Flavin, holding court at the end of the bar, tells me this convivial atmosphere is exactly what he was aiming for when he opened Halibut Point in 1982.

“I made sure I built the place for little kids, old people, and single women,” Flavin says—and he means that literally. He and some friends constructed an addition on the back of the building, handcrafted the wood bar, and filled the space with historic memorabilia—much of which is related to Howard Blackburn, a fisherman-turned-entrepreneur who built the brick building in 1900 and whose name is carved into its fac?ade. Blackburn is likely Gloucester’s most famous citizen, and Flavin bears something of a likeness to the legendary figure. A portrait at the end of the narrow space bears witness to this, while also telling the tale of Blackburn’s most harrowing adventure. In the portrait, his one visible hand is bandaged—Blackburn lost all his fingers and thumbs to frostbite when his fisherman’s gloves went overboard in a dory during a sudden winter storm. Knowing his hands would freeze, he held them in a curved position so they would still slip over the oars of the small boat. He was rescued five days later, after rowing himself to shore with frostbitten fingers.

Unable to return to work as a fisherman, Blackburn opened a tavern in 1886, ultimately establishing the brick building that now houses the Halibut Point pub. Through the years, the building has accommodated everything from a Laundromat to a travel agency, though much of the original de?cor was removed. Flavin has spent decades reassembling it— Blackburn’s old cash register holds a place of honor behind the bar, though it’s no longer used. The staff uses a touchscreen to tally orders now—a tool that almost cost Flavin his longtime staffers.

Halibut Point’s pub interior is loaded with memorabilia

Halibut Point’s pub interior is loaded with memorabilia

“You should have seen all us old guys trying to figure it out,” says Flavin, who doesn’t even have a cell phone.

For a certain type of North Shore haunt, change comes slowly—or not at all. Regulars are resistant to new de?cor or menu items, and maintaining that balance can spell decades of success or speedy failure. Halibut Point’s menu has remained virtually unchanged for decades—from Flavin’s original recipe for clam chowder to the lack of fried food— although that’s not for lack of trying. A few years back, Flavin’s daughter, Mercedes, came to work at the restaurant with her husband, Michelin-starred chef Paolo Laboa, and tried to modify the menu.

“It was anarchy,” recalls Flavin. “I got phone calls, I got letters…. People were so used to coming in, they didn’t even look at the menu, they just ordered.” After three or four months, he says, things weren’t going well, so they changed everything back—even the bread.

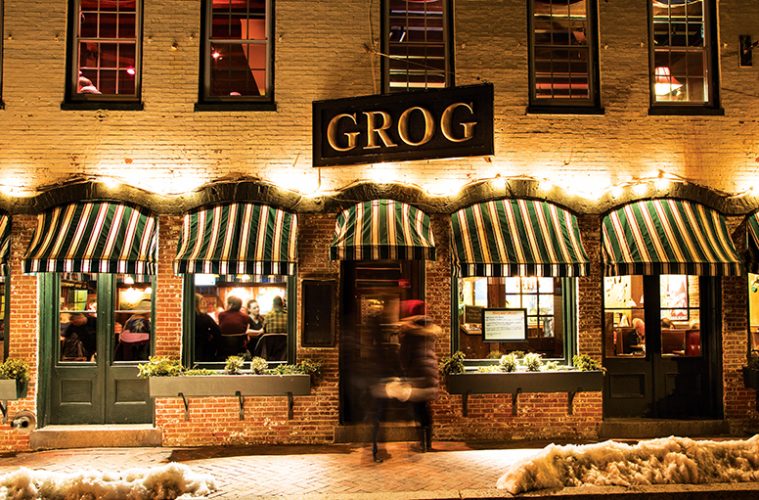

Bill Nichelmann understands the weight of tradition all too well. He and his wife, Nicole, now run The Grog, the legendary pub in Newburyport opened by his father-in-law, Richard Simkins, in 1970. With 400 seats—more than four times the number at Halibut Point, Nichelmann has a bit more leeway with the menu, but he still wants to stay true to his father-in-law’s vision and the vibe of the space, which has been a tavern nearly continuously since just after the Civil War.

The low ceilings, dark paneled walls, and wood-burning fireplace all speak to another century, enlivened by original Art Deco posters advertising bitters and 1950s movies that hang alongside striking plaster-cast hand-painted fish Nichelmann bought from “a random hippie” years ago. The clientele is equally eclectic—local families with small children, young people, senior citizens, and tourists pack the booths, enjoying a varied menu ranging from classic burgers and chowder to standout crab cakes and a sweet potato burrito that has been on offer for more than 15 years. Blue-collar workers, lawyers, neighbors, and employees from area restaurants all rub shoulders at the bar, taking their regular seats every afternoon at 3 p.m. to meet up with friends. The famed live music scene attracts a host of artists, including legends from across the country who have been playing at Parker Wheeler’s Blues Party every Sunday night for 24 years.

Over the brutal winter, Nichelmann remained open daily, so as not to disappoint neighbors who arrived on skis, snowshoes, and fat-tired bikes for a little camaraderie and some hot food.

Tweaking a menu with such a long history and maintaining consistent high-quality food is a balancing act. The Grog has always sold casual American food, with an emphasis on fresh seafood and a few quirks, like the Mexican section with its terrific fish tacos—a hold-over from when the upstairs space was a Mexican restaurant. The menu changes every six months, but not much, and the top-notch chefs show off their skills with specials and an elegant catering menu.

“We want to generate excitement and not become stagnant but preserve the old feel,” Nichelmann says. That isn’t always easy when it comes to the de?cor—tables and chairs break, and none of the drawers work on the host stand, but you can’t just replace them with new and still maintain that scruffy charm.

“I am constantly repairing and replacing things, but we can’t use brand-new wood,” Nichelmann says. “It’s difficult to replace things and still have the feeling people expect at The Grog.”

|

Preserving a certain feeling is critical when it means pleasing generations of customers. Winchester natives can’t imagine the town without Lucia. Since opening in 1986, the Italian spot has hosted family dinners, christenings, bridal showers, and locals who are just seeking a consistently delicious meal. At well-spaced tables in the main dining room, smartly dressed patrons enjoy trays of pre-dinner martinis under a vaulted ceiling painted like the Sistine Chapel. Donato Frattaroli, who also owns the storied North End spot by the same name and two Artu restaurants in Boston, has invested his heart and soul into his family’s business, and it shows. Frattaroli presides over the large dining room, greeting customers and waving to passersby on the sidewalk, but he is not afraid to get his hands dirty.

“If I lose a cook or a pizza guy, I know I can jump in and replace them,” he says simply. After all, Frattaroli has done every job in the restaurant. He and his brothers, Filippo and Tonino, found work in the North End after emigrating from Italy, and opened Lucia in Boston in 1977. “It was quite literally a family affair,” Frattaroli says. “My entire family throughout the years has worked there, from my mother, Lucia (the restaurant’s namesake), to my youngest son.”

Nearly every item on the menu has a story, from the Vitello Bracciolettine to the Torta Nocciola, a hazelnut cake made from a recipe Frattaroli’s sister picked up at a cooking school in Italy 25 years ago. Regulars know the Pasta alla Chitarra is close to the family’s hearts—the handmade spaghetti, named for the guitar-like gadget used to cut the long, thick noodles, was a staple of Frattaroli’s youth. Rustic yet elegant, the toothsome pasta is served with a fresh, light tomato sauce or topped with a decadent combination of wild mushrooms and white truffle oil.

The menu may appear to be unchanged, but the arrival of chef Pino Maffeo a few years back brought new energy to the cuisine. Maffeo is unassuming, preferring to let the restaurant’s tradition and recipes take center stage, but in subtle ways, and through nightly specials, he has made his mark. Perhaps some sauces are a bit lighter to accommodate delicate palates, and more ingredients are organic, quietly attracting new fans without upsetting the stalwarts.

“We try to keep the menu as consistent as possible to provide our guests a level of familiarity,” Frattaroli says. “The long-term success of the Winchester location is really all about time spent there and creating strong relationships with all of our patrons. Winchester is a wonderful, tight-knit community—being a part of that is really special.”

With only 19 years in business, Periwinkles could be considered a new kid on the North Shore block. After all, neighboring establishments along its scenic stretch of Route 133 date back before World War II. But the building housing Periwinkles, set on a beautiful inlet on the Essex River, has been welcoming people for a meal for nearly half a century. And owner Tom Guertner has worked in the restaurant business in Essex almost continuously since 1981.

Word traveled quickly when the spot dug out from mountains of snow to open for the season the first weekend in March. Locals tired of the dregs of winter lined up to grab a reminder of summer and a seat in the cheery space, highlighted by large windows, white beadboard-covered walls, and a gallery of local artwork.

The white tablecloths and china and an upscale menu set Periwinkles apart from the clam shacks down the road, which is not to say they don’t truck in the popular bivalve as well. Fried clams are consistently a top seller, along with clam chowder that won first place 13 of the 15 times it entered the Essex Chowder Fest.

But one of the restaurant’s more popular dishes is a bit more elegant—the Warm Tomato and Goat Cheese Salad topped with a piece of local baked haddock is consistently a top seller. The classic New England baked haddock is also a favorite with tourists and locals alike. Guertner gets his day-boat fish from Ocean Crest Seafood in Gloucester, and can go through more than 200 pounds a week during the busy summer season. With Guertner in the kitchen and his wife Cathy managing the front of the house, he says they are able to maintain a consistency that keeps people coming back.

Ask any restaurateur who has had the same eatery for decades, and they will agree that consistency is key. “I’ve been here so long that people who helped me open it had kids, and their kids work here now,” says Halibut Point’s Flavin. And when generations keep returning to the same spot, it creates a sort of communal muscle memory that makes even strangers feel right at home. “You come in here by yourself, I guarantee you’ll find someone to talk to—I don’t care if you’re 10 or if you’re 90,” says Flavin. “This place would blow away Cheers.”

Halibut Point’s pub interior is loaded with memorabilia

Halibut Point’s pub interior is loaded with memorabilia Lucia owner Donato Frattaroli

Lucia owner Donato Frattaroli