Thoughts of a trip to Massachusetts’s North Shore don’t immediately conjure images of viticulture—that is, vines laden with grapes strung across trellises, stretching over green valleys as far as the eye can see. That’s a picture typically associated with California rather than the Bay State, a region known more for its beer than wine. Beer, after all, has been part of Massachusetts’s identity from the days of the Puritans all the way up to the booming independent brewing scene of 2019.

But beer isn’t the only type of alcohol being made along the North Shore. The area boasts its fair share of vineyards, too, and those vineyards also connect to the state’s long history, and keep it alive in their own way.

Take Topsfield’s Alfalfa Farm Winery, family-owned and volunteer-run since 1994, the year that grapes were first planted in its soil. (The winery opened to the public the year after.) This was 20 years after the land was purchased by Richard Adelman, back in 1974 when the farm the winery now rests on went out of business. “It was probably one of the first dairy farms in Massachusetts to go out of business,” says Trudi Perry, who is both the winemaker for Alfalfa Farm and also its resident historian. Talking to her means getting a rich, insightful lesson on local antiquity, from the property’s heyday, when it operated as a 600-acre dairy farm, to its closure and eventual parceling in the 1970s to now. Currently the land serves as home to the winery as well as to condos, an apple orchard, and a senior living center.

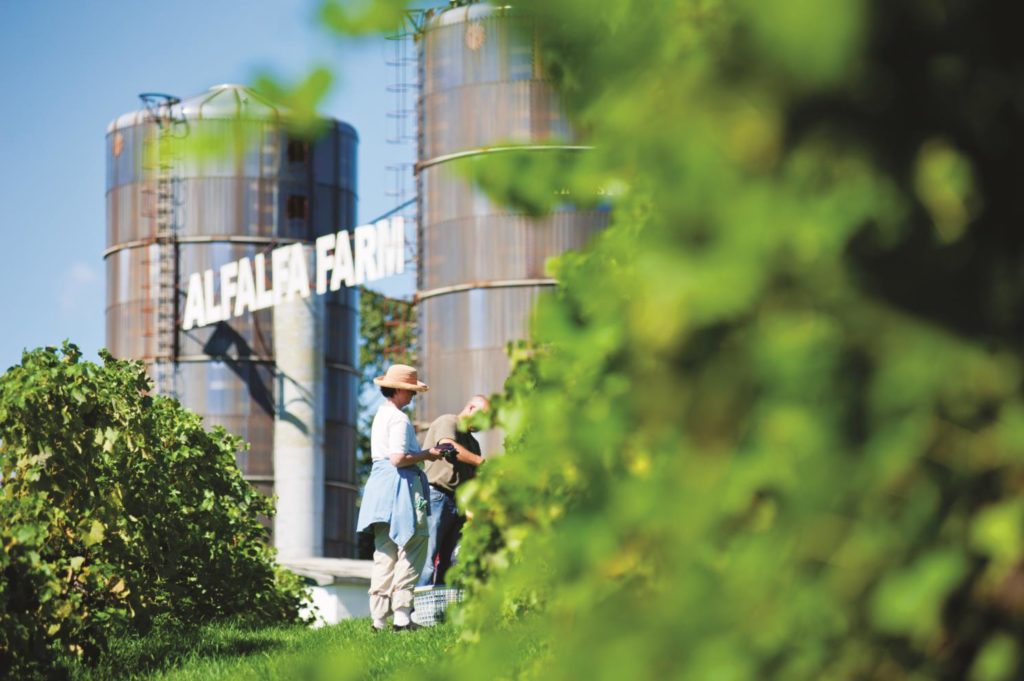

Even the construction of I-95 plays into that narrative. “When they put Route 95 in,” Perry explains, “they kept a tunnel under 95 so the cows could still pasture on the other side.” To visit Alfalfa Farm Winery is to visit a confluence of past and present. Cars whiz by on I-95, the twin silos bearing the winery’s name tower over the barn and the patio, the vines lie between the highway and the field, and all around stand reminders of what this property used to be, including the house where the owner of the farm lived and the three apartments that housed the farmhands. Alfalfa Farm Winery is very much coupled to its history, and history is an integral part of its character. “That’s why the Adelman family wanted to keep it agricultural,” Perry notes. Making great wine—and for the skeptics, Alfalfa Farm Winery does indeed make great wine—comes first and foremost, but preserving history is a very close second.

The story’s much the same for Donna Martin, owner of the small but prolific Mill River Winery, settled alongside Route 1 over in Rowley. “This used to be a place called Dodge’s Cider Mill back in the 1890s,” she says on a tour through the winery’s fermentation room. “In those days, a long time ago, this is where people would come on their horse and buggy to buy their cider and bring their families.” When Martin first laid eyes on the property more than 10 years ago, she knew she had to jump on it; the opportunity to build her business on a piece of colonial history was too good to pass up. “I really wanted to revitalize it and make it back into an agricultural setting, like it was back in the 1890s,” she says, “and really just celebrate that.” (The winery’s planning on putting out a hard cider for that exact purpose, too.)

Mill River’s emphasis on bringing the past into the present marries well with Martin’s overarching mission of bringing California flavors from the Bear State to Massachusetts; it isn’t just a coincidence that Mill River flies the California state flag. For Martin, with a Ph.D. in analytical chemistry, the goal is creating wines that mirror Californian wines via science. She points to research conducted at Cornell University and the University of Minnesota that has yielded wine grapes both sturdy enough to thrive in the New England climate and equal to California-grown grapes in flavor. Perhaps to no one’s surprise, New Englanders love drinking California wines. The idea of finding wine of that persuasion made in one’s own backyard is enticing.

“Now the technology has gotten to a point where we can grow grapes that we can ferment and make into wines that are dry, with a tannic structure that’s able to rival a merlot that would be grown in California,” says Martin, visibly excited by the shop talk. (You’d need a blind taste test to say for sure, but Mill River’s Merlot certainly stands out on its own merits.) Her ultimate vision is to create a whole new identity in Massachusetts by sculpting it into a wine region while maintaining that classic agrarian identity; modern tech blends with Old World character, charting a fresh course for the state going forward.

Taking an alternate approach, Alfalfa Farm keeps its emphasis strictly on the Old World and the agrarian; exiting off of I-95 and driving into Topsfield is like entering a time warp. That’s the way the team prefers it, though the cars whizzing by on 95, visible from the winery’s patio, remind visitors of Massachusetts’s modernity right alongside its idyllic roots. And necessary as the reminder may be, the proximity to 95 poses its own set of challenges for “making it economically viable,” according to Perry. “We grow four different kinds of grapes here,” she says, indicating the vines are nestled between the farm silos and a chunk of nearby wetlands.

“We make probably 25 percent of our wine, I suppose, from the estate-grown grapes,” she explains, noting that Alfalfa Farm supplements its local harvest with grapes and juice from California in the fall and from Chile in the spring. On top of that, they also buy blueberry juice for their blueberry wine, a particularly delicious drink that highlights the qualities of the fruit—its balance of sweet and tart—far better than the average blueberry-forward beverage.

But being volunteer-run adds increased difficulty to the art of winemaking, and being a farm winery is an obstacle unto itself; for instance, farm wineries weren’t allowed to sell at farmer’s markets until 2010. “We approached the Town of Topsfield to allow us to sell at Topsfield’s farmer’s market,” Perry says. “And that’s when all the towns were going through this big upheaval. They didn’t have the right licenses. No one knew what they were doing. It took us five years to be able to satisfy what they wanted.” As if these challenges aren’t enough, Alfalfa Farm is making wine the old-fashioned way: with an antique wine press, or more accurately a barrel press.

There’s no better way to represent viticultural history than with this erstwhile tool of the trade. But both of these wineries also let consumers experience that history, as well as the history of the state they call home, through their location, through their character, and through the qualities of the grape, a new piece of Massachusetts’s identity, but a piece of history all the same. millriverwines.com, alfalfafarmwinery.com