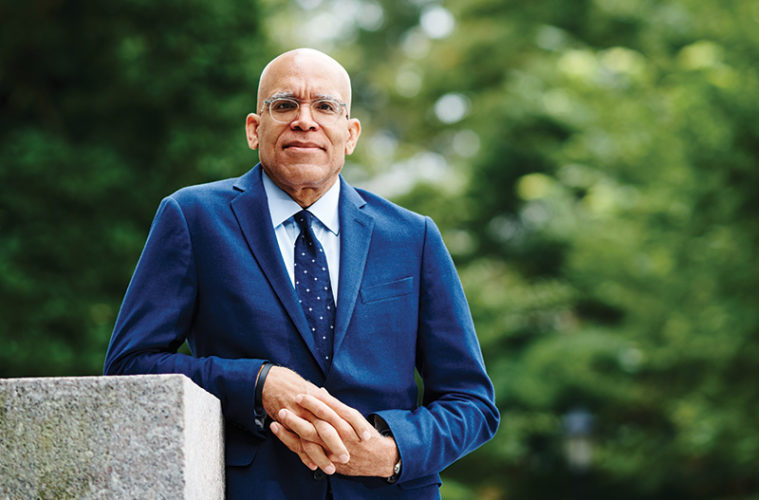

Diversity isn’t typically the first word that jumps to mind when considering elite prep schools, but as Raynard S. Kington, MD, PhD, MBA, head of school at Phillips Academy in Andover points out, the promise of diversity has always been part of the school’s DNA.

“Even in its founding documents—and it was founded in 1778—there was a pledge to admit youth of requisite skills ‘from every quarter,’” he says. “Even in the 1700s, they had this notion that the school would have a diverse student body, and not just wealthy kids. So, that history and that culture of commitment really resonated with me in lots of ways.”

That resonance is easy to understand. As Kington noted in an op-ed for Newsweek, he is the “first African American and the first openly gay head of school in the academy’s 242 years of existence.”

Kington began his tenure at Andover in July 2020, as the school—and the nation—grappled with both the COVID-19 pandemic and the murder of George Floyd. In many ways, he’s the perfect person to guide the school through this moment in its long history.

Before spending a decade as president of Grinnell College in Iowa, Kington’s career focused on health and science. He served as principal deputy director and acting director of the National Institutes of Health; a division director at the CDC; director of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey; a senior scientist at the RAND Corporation; and assistant professor of medicine at UCLA.

His research has focused on diversity in the scientific workforce and social determinants of health, which are non-medical factors, like housing, education, and nutrition, that have an outsized effect on people’s health outcomes.

That combination of work in public health, higher education, and equity—plus his personal experiences—means that Kington is uniquely positioned to lead Phillips Academy right now. “I think in many ways it was a great preparation for coming here,” he says.

For instance, he notes factors that are important to health outcomes, like economic status and race, also profoundly affect educational outcomes, since not every student has access to advantages like books, the latest technology, special programs, private tutors, or summer courses.

“That’s made me a bit more sensitive to those factors like economic status and how we have to do a better job in how we use our resources to diminish the impact of those factors, but also think about how those factors might affect how an applicant looks to us,” he says.

Connecting across generations

Kington also says he has a “deep connection” with institutions whose missions are committed to excellence and the preservation and transfer of knowledge to new generations.

“I very much resonated both with Andover’s history and commitment to excellence in education and its commitment to really opening its doors to diverse students,” he says, adding that Andover demonstrates this with its need-blind admissions—rare among elite prep schools—and commitment to meeting 100 percent of each student’s demonstrated financial need with grants.

The school’s commitment to diversity applies beyond socioeconomics. Kington called Andover “very much a global institution,” with students from 26 countries in the entering this year.

“What impressed me about coming here was the recognition that these different life experiences enrich the educational experience for everyone,” he says.

That’s not to say Phillips Academy doesn’t still have work to do. Although it graduated its first Black student in 1849, things haven’t always been easy for students who don’t fit the stereotypical prep school mold. Kington notes the existence of the Instagram account Black at Andover, which details some of the racist experiences Black students have had there. The Andover Anti-Racism Task Force, which the school established in September 2020, aims to “examine Andover’s policies, practices, and institutional biases with respect to race.”

Kington hopes that he can help the institution to continue to improve and excel, as well as respond to this generation’s demands for equity in terms of race, gender, social class, “and all the other dimensions of openness that we believe in.”

“We have to figure out how we live those values in a changing world. The greatest risk of great institutions is that they sort of drift into mediocrity,” he says. “I hope my legacy is that I help the institution continue to respond to a changing world and continue to adhere to high standards of excellence in the context of a different world.”