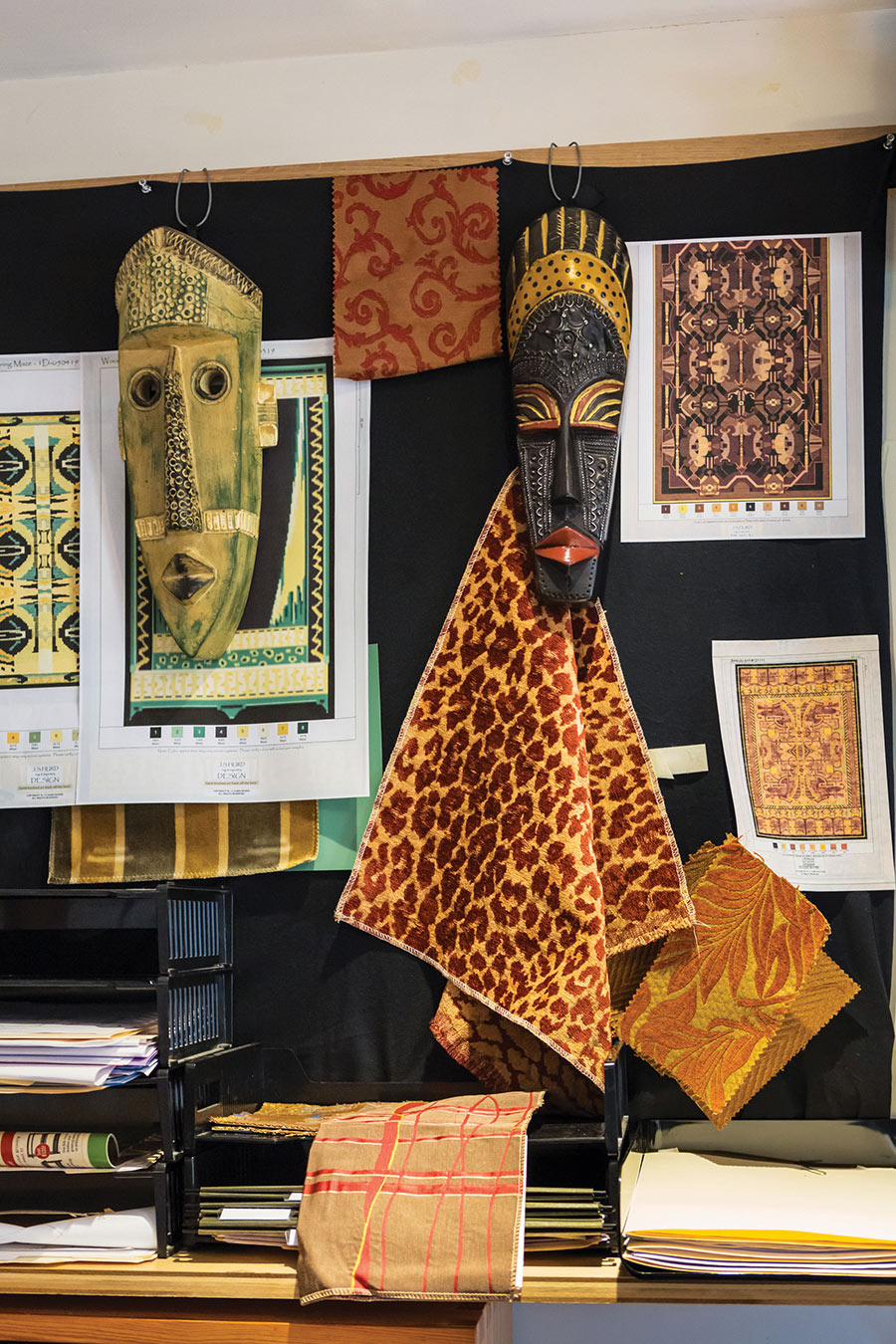

Joanne Hurd walks through the rooms of her Gloucester home pointing to rugs on the floors and tapestries on the walls. Abstract shapes and swirling colors become animal heads as she points to elements of the design. Some look geometric and tribal, some build on nautilus or fern shapes, and still others resemble the softly hued patterns of aged Aubussons. Upon closer inspection, they all reveal hidden images, interlocking designs, and shifting shapes and patterns that could be creatures or ancient motifs. Look again and a tapestry that seemed to depict primitive masks becomes a piece of abstract art.

“I don’t know where the designs come from,” she says. “They seem to find me, often in the night. For me, creating these designs is like returning to childhood and playing with colors, lines, and textures.”

For 40 years, Hurd has worked as an interior designer specializing in kitchens and bathrooms. Her clients, whose home bases range from the North Shore to greater Boston to California, have come to her for what she calls “a marriage between function and aesthetics. My signature style is what the client wants,” Hurd says. “What I love doing is educating people about the effects of their design decisions.”

In 1980, her brother, Ken, an architect and designer specializing in hospitality projects, was developing a design for the Towers Lobby of New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel. He asked Joanne to create a rug for the space. “I drew it out on vellum, with colored pencils, and was over the top with excitement,” she says.

That was just a brief interlude in her own growing kitchen and bath design business, but she never stopped drawing on paper with pencils. “I’ve always been an artist,” Hurd explains. “From the time I was a small child, I loved drawing rhythmic patterns. In 2006, I reignited my love affair with textiles when I found myself drawing rug designs with colored pencils, sharpener at the ready. It is an extremely time-consuming process and I thought, ‘There must be a CAD (computer-aided design) program that does this.’ When I found one and tried it out, I was blown away.”

Eventually Hurd met a representative from a Nepalese rug company, who connected Hurd with weavers in Katmandu. “He and I have developed a good working relationship,” she says. “He has the same computer program as I use, so he can produce the rug design from my graph and put the knots exactly where I want them.”

Hurd created her first rug for clients in 2011. She had designed a new kitchen for them, and they liked the process of working with Hurd so much that upon completion, they asked what else they could do together. When she suggested a custom rug for the living room, they enthusiastically agreed. “We designed and produced an 11- by 15-foot rug that has the colors, details, and motifs they liked. They liked soft colors, and for the rug to look as though it had been around for a while. The design was carefully composed so that it showcased their furniture. That first project went so well that I was hooked. Ever since, I have been trying to reduce my interior design work so that I can do more of this.”

To design her rugs and tapestries, Hurd relies on a chest holding 1,400 yarn samples, each representing a shade of the Tibetan wool used in her rugs and tapestries. “It’s my jewel box of yarns,” she says with a smile.

Weavers in Nepal hand-knot the yarns on upright looms. Some of Hurd’s designs are augmented with silk from China. “Most of my rugs now are made with 100 knots per square inch,” she says. “That gives me the level of detail I need. But more detailed designs have 150 knots per square inch.”

She points out the difference in quality between hand-knotting, which is the process used by the Nepalese women who weave her rugs, and tufting. “That utilizes a tufting gun, which is much faster and requires no specialized skill set, and produces a piece with substandard quality and durability, as compared to a rug made with hand-tied knots.”

Depending on the size of the finished piece, the process takes between 12 and 16 weeks. Hurd proudly points to the GoodWeave label on her rugs, which provides assurance that no child or forced or bonded labor was used in making them.

To date, she has produced over 70 designs, some of which express the same patterns in different colorways. She especially likes to hang her designs on the wall, as opposed to laying them on the floor. “Wall art allows me to create the piece as a composition,” she says. “On the floor, a piece does not have the same impact as when it’s hung on a wall, which turns it into an embellishment, or an accessory.”

Her rugs may be spread out underfoot, softening the way, or they can act as more focal accessories to a composed interior. But whether they lie on the floor or hang on the wall, there is no doubt that they are art.